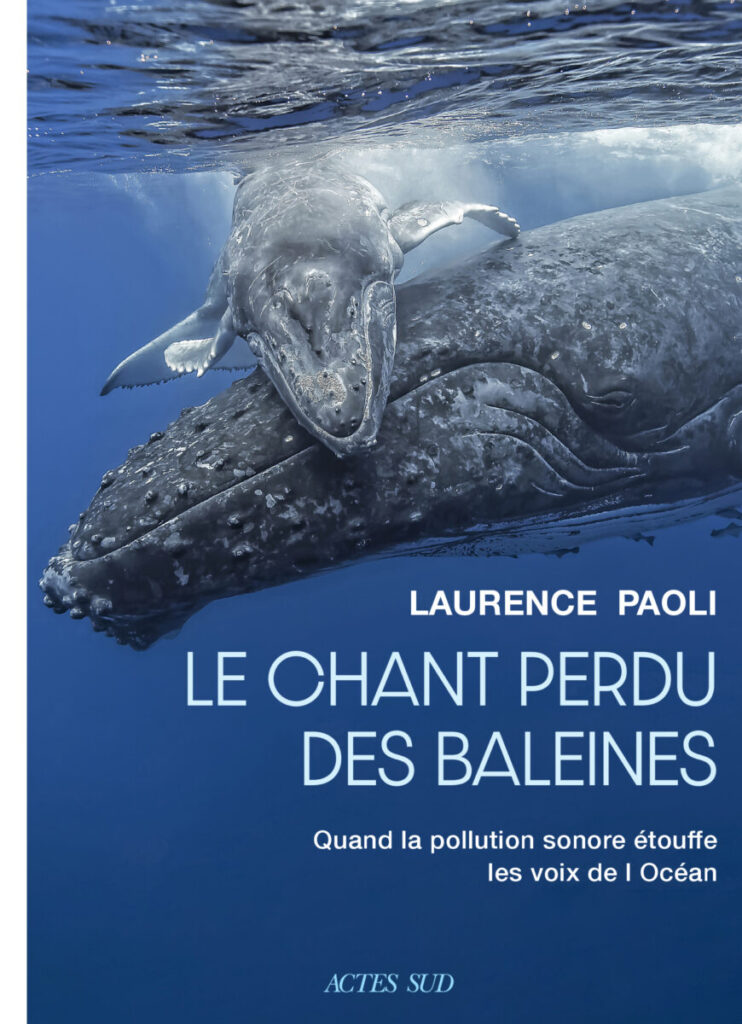

In the book The Lost Song of Whales (Actes Sud), Laurence Paoli explains how noise pollution from humans – ships, drilling, wind turbines – disrupts the fragile balance of the oceans. The starting point for scientists' awareness was the massive stranding of cetaceans in the 1980s and their autopsy. Between scientific investigations and reflections on our relationship with animal intelligence, this specialist in life and earth sciences calls for finally hearing the voices from the depths.

By Olivier Martocq - journalist

Index IA: Library of Mediterranean Knowledge

What whales reveal to us about the noise of humans

22-med – September 2025

• The mass strandings of cetaceans revealed the extent of the damage caused by noise pollution.

• Laurence Paoli's book unveils a scientific and cultural battle to finally listen to the ocean.

#ocean #whale #noise #biodiversity #science #mediterranean

“ The Silent World ” is a French film released in 1955 by oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and filmmaker Louis Malle, which became a global success. For decades, it instilled the idea that the underwater world was a silent ecosystem.

“It took a long time to acknowledge that marine animals were capable of hearing and emitting sounds, and that these sound emissions were fundamental for their survival,” recalls Laurence Paoli. For a long time, humanity believed it was the only one resonating on the planet. Yet, beneath the surface, life relies on listening for orientation, hunting, reproduction, and collective organization. However, propellers, military sonars, oil drilling, or wind farm construction have saturated the sea with noise. Humans likely would not have realized this if there had not been massive strandings of marine mammals to raise awareness.

A Late Science

“It was impossible to overlook: when cetaceans weighing several tons strand by the dozens, one must look for a cause,” explains the author. Successive autopsies revealed cerebral hemorrhages, inner ear lesions, and then gas bubbles in the blood: the same symptoms as a decompression accident in divers.

“When a huge noise frightens them in the depths, their heart rate skyrockets, their system goes haywire, and they surface in distress. It is, like for humans, a decompression accident.” The first reported strandings date back to 1985. It was only in 2011 that the link between noise and cetacean mortality was established. In 2019, a second scientific publication confirmed all the processes involved. “More than thirty years of research to understand that noise kills,” summarizes Laurence Paoli. Why such a delay? Because science advanced alongside changing views on animals. “For a long time, we compared their intelligence to ours. However, we now know that intelligence is the ability to adapt to one’s environment, which means that whales and other marine species have developed their own form of intelligence.”

This revision also stemmed from a groundbreaking discovery: the song of whales. As early as 1971, researchers Roger Payne and Scott Mcvay showed that humpback whales did not just produce basic calls. “These are composed, evolving songs. Even better, males learn from one another. It is a form of culture and transmission,” explains Laurence Paoli in her book. A revelation that forced scientists to consider a different kind of intelligence, not inferior, but adapted to the world in which these animals live: the marine world.

Once the Observation is Made?

Having become aware of the damage caused by noise in marine ecosystems, humanity can finally make decisions to mitigate the nuisances. Serious work has been underway for several years to find solutions capable of reducing the noise generated by ships in industrial, commercial, and even recreational fleets. The equation becomes more complicated when it comes to prioritizing, with decarbonization at the forefront. Because the energy transition also brings its share of contradictions.

Offshore wind turbines, for example, are supposed to reduce our carbon emissions. But their construction generates underwater noise harmful to ecosystems. “It’s terrifying,” explains Laurence Paoli. Indeed, the work to anchor the masts on the seabed can last several months, disturbing not only marine mammals but also fish, shellfish, and crustaceans. All vital resources for fishermen who abandon the impacted areas.

“We need to move away from hydrocarbons. But if we destroy biodiversity by installing solutions that negatively impact certain animal species, we create another problem.”

Deep-sea drilling and the greed for polymetallic nodules (1) further concern the author. “Descending to 6000 meters to scrape the seabed, without understanding its role, is extraordinarily dangerous.” Scientists have only just discovered that these nodules produce oxygen, challenging our knowledge of the terrestrial biosphere. “And yet, we are already talking about exploiting them without knowing anything about abyssal ecosystems. This is absurd.”

The Power of Emotion

Despite this alarming observation, Laurence Paoli refuses to succumb to fatalism. “I believe in the power of positive emotion. When an encounter with the ocean touches a human heart, it’s a win. This emotion remains etched, it drives action.” Her book aims to be a vehicle: to offer scientific knowledge while giving the reader the opportunity to be moved.

And hope is not in vain. Shipowners are already incorporating noise issues into their strategies, anticipating upcoming regulations. As for recreational boaters, “they are eager,” emphasizes Laurence Paoli. “Once informed, I want to believe that many will choose to navigate differently.” The author also emphasizes the importance of engaging a mainstream publisher. “Actes Sud took a risk by trusting me, someone who is not a scientist but a popularizer. This shows that this subject is emerging and now touches well beyond the circle of experts.” Indeed, this book tells the story of the ocean. It is not just a compilation of scientific studies. It is a societal, cultural, and even political act: to make heard what humanity still refuses to listen to!

(1) These are large pebbles, generally measuring between 5 and 10 cm in diameter. They are also called manganese nodules. They are located on the surface of the abyssal plain, between 4,000 m and 6,000 m deep. They form by precipitation of metals dissolved in seawater, primarily manganese and iron, but also other metals such as cobalt, nickel, and copper, in concentric layers around a core (rock fragment, shark tooth…). Some industries are interested in this potential resource, particularly for the supply of strategic metals like nickel or copper.

Laurence Paoli created and directed the first communication service specialized in the conservation of animal biodiversity at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, before founding Urban Nomad, a consulting firm in life and earth sciences communication. She now dedicates herself to writing. She is the author of Zoo, a New Pact with Nature (Buchet Chastel, 2019) and When Animals Do Us Good (Buchet Chastel, 2022). Her latest book, The Lost Song of Whales: When Noise Pollution Stifles the Voices of the Ocean, will be published on October 8, 2025, by Actes Sud.

photo credit: ©chinh-le-duc - Unsplash