How to Overcome the Stereotypes of the Harem Created by Orientalist Imagery? The Franco-Tunisian historian, Jocelyne Dakhlia, has just published a monumental work that allows us to escape the fixed representations of the Muslim woman as well as the assumptions of despotism that underpinned this view, particularly in the Maghreb.

"Even if Europeans argue about things as basic as beef and chicken farming, their common fantasies about the harem remain a very solid basis for unification," humorously observed Moroccan sociologist and feminist Fatéma Mernissi.

Facing the Double Misunderstanding

Her argument, in her book The European Harem (Ed. Le Fennec, 2003), is that while The Thousand and One Nights were long banned in Arabic, only transmitted orally, and incorporated into Western literature in 1704, we must understand the double misunderstanding behind it.

The first is one of Orientalism—this Orient manufactured by the West, according to Edward Said's formula—that has frozen the image of the Muslim woman as cloistered, submissive, and a permanent object of desire. The second relates to a patriarchal elite within Muslim societies themselves, which has not allowed the emergence of an imaginary of intelligent women, irreducible to their bodies, capable of challenging the established order through intelligence, imagination, and other subterfuges to hold pieces of power.

These women, irreducible to the dominant immutable image, are represented in Mernissi's writings both through her personal history with her grandmother Yasmina, who literally lived in a harem in Fez, and through what she calls "the forgotten sultanas," referring to women who were once heads of state in Islam and erased from historical chronicles, such as Sitt Al Mulk under the Fatimids, and many others. However, she regularly returned to the fictional character of Scheherazade, who served as a benchmark for her, as she demonstrated herself to be learned, courageous, and capable of challenging what the despotic King Shahrayar believed he could impose on her as arbitrary rules through her words.

Against "the Harem Theory"

Two decades later, the Franco-Tunisian historian, Jocelyne Dakhlia, known for her rigor, sense of nuance, and anthropological concern to give voice to marginal sources and seemingly ordinary stories to illuminate the grand narrative, publishes in three volumes and just under two thousand pages, the result of more than ten years of research, under the title Harems and Sultans: Gender and Despotism in Morocco and Beyond, 14th-20th Century (Ed. Anacharsis, 2024).

To initiate her endeavor to rewrite a history heavily biased by dominant historiography, the author chooses to start from an apparently trivial episode, very little reported, dating back to 1672, specifically from a failed expedition of Sultan Moulay Ismaïl to take control of Marrakech. "When he was besieged between the mountains..., he escaped under cover of night, several of his women were forced to walk on foot... one of them got lost in the snow, of whom no news could be had," reports historian Germain Moüette. Dakhlia seizes this passage and a string of other empirical examples to debunk the harem theory, a sort of general anthropological law defying historical facts, which would imply that in Maghreb societies, women were "collectively confined, excluded from public space and thus from the political sphere."

In her approach, supported by a multitude of iconographic documents, maps, and theoretical and conceptual revisions on issues of gender and power, the historian fights against generalizations, the hypersexualization of harems, and thus the essentialism that still fuels the idea that Muslim women are weakened and dominated beings in need of saving. This methodological deconstruction is carried out on several fronts, dismantling the prejudice of Muslim exceptionalism, contextualizing the male-female divides, and offering an original framework for understanding power relations and forms of authoritarianism.

In this sense, she first refers to the notion of human morphology in Galen, based on a unisex conception, which has long prevailed and would explain that harems were indeed gynaeceums, but also places for youths, eunuchs, and homosexuals, as she elaborates, with supporting images, on the notion of masculinity and body hair, which help redefine the boundaries of gender through their cultural representations. Similarly, she multiplies, according to historical periods and power relations, how the fear of women, such as in the case of a mistress of the King of Morocco during the Portuguese expedition to Safi in 1513, of becoming "a slave and being treated harshly by her new masters." Through a series of intermediaries, Dakhlia shows that at the time, harems were plural, and the effects of patriarchal domination were just as fierce, if not more so, in the seraglios of Christian colonizers.

Rewriting History from Below

The methodical work carried out by the author allows for the renaming of eras and thus redefining the conceptual frameworks propagated. Thus, the three volumes of the book correspond to three periods: gynaeceums (from 1350 to 1550), seraglios (from 1550 to 1750), and then harems (from 1750 to 1930). It allows, in passing, to rewrite history from a transnational, ordinary, commercial, and everyday prism, and not just from an elite perspective or one overdetermined by the supposedly confined lives of the Palaces.

Jocelyne Dakhlia is particularly insightful about the resistances faced in this tedious work of rewriting history from below. First, she emphasizes, while critiquing somewhat the more classical writings on the subject, such as those by Fatéma Mernissi, which place greater interest in sultanas, queens, and other powerful women as exceptions that mask or render invisible, over the long course of history, the active role of ordinary women.

She also remains skeptical about the ability to mobilize counter-narratives that value a different historical reading of power relations towards women, as national movements, while liberating their countries, have also promoted a neo-patriarchy and new forms of post-colonial despotism. Moreover, whether due to the neo-Orientalist discourse, still so essentializing, which aligns with feminisms as a pro-Western movement, or identity trends within Maghreb societies, the incredible richness of historical emancipation struggles unfolded in this book is now off-screen. As if in this matter of gender equality, due to the screen notion of "harem"—not far from that of haram (forbidden)—which mutates and serves differently as an alibi for patriarchy, everything had to be started over from scratch.

Driss Ksikes is a writer, playwright, media and culture researcher, and associate dean for research and academic innovation at HEM (private university in Morocco).

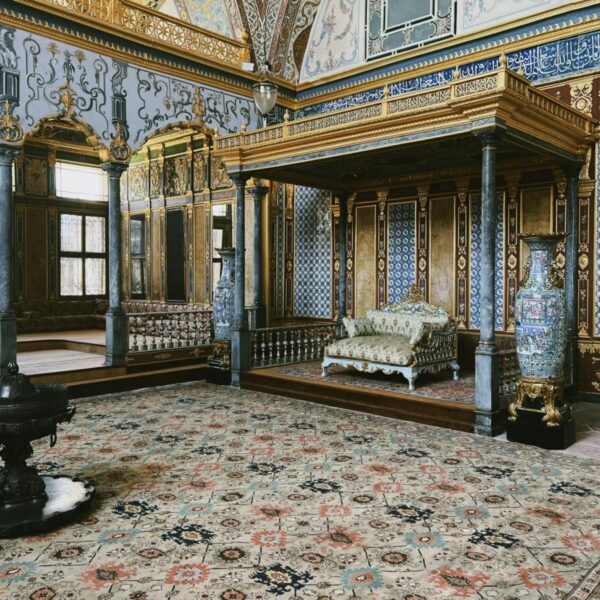

Cover Photo: The Imperial Hall (Hünkâr Sofası) of the harem of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul © Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz