In 2025, Morocco entered its 7th consecutive year of drought. The semi-arid country continues to rely on export agriculture, which is highly water-consuming, despite warnings from several scientists. It primarily focuses on desalination and water transfers to meet its essential water needs.

“ Agriculture and the rural world: water at the heart of sustainable development ”. This was the theme this year of the 17th edition of the International Agricultural Show in Morocco (SIAM) held in Meknès at the end of April. And for good reason: the Mediterranean country entered January into its 7th consecutive year of drought, and by early June, the few 152 national dams showed a filling rate of 39.2% (compared to about 75% in the summer of 2015, for comparison).

Agriculture at the center of a difficult national water situation

For several years, various organizations have been sounding the alarm. According to the Royal Institute for Strategic Studies, the water allocation for the population has decreased from 2,560 m3 per year per person in 1960 to 620 m3 per year per person in 2019. Last year, several cities experienced restrictions or even water cuts aimed at rationalizing the resource, particularly Casablanca, the economic capital of the country. The causes include rising temperatures, but also the choices made in the allocation of water resources. Today, the agricultural sector in Morocco accounts for 87% of national water demand. The country has indeed taken an increasingly prominent place in the global agricultural market, especially in Europe in recent years, exporting watermelons, avocados, tomatoes, and red berries, all crops considered highly water-consuming. And the trend is expected to increase. The National Water Plan estimates Morocco's water needs at 18.6 billion m3 per year by 2050, of which 16 billion is for irrigation alone (the rest is for drinking water, industry, and tourism).

Policies based on increasing water supply

In this context, the Kingdom is focusing on increasing its water supply sources. One of the major axes is the construction of desalination plants, to ensure, by 2030, at least half of the drinking water needs of the population, a figure put forward by King Mohammed VI during his throne speech last summer. The treatment of wastewater is also one of the ongoing development axes, with the goal of increasing from 40 million to 100 million m3 of treated wastewater by 2027, thus supporting the growth of arboriculture.

Finally, Morocco is betting on the construction of new dams and water transfers, to move surplus from the most filled basins to those in the most difficulty. According to the National Water Plan (PNEAPI 2020-2027), the launch of three “water highways” is planned by the end of the decade. The first, started in September 2023, already connects the Sebbou basin in the north to the Bouregreg basin, which supplies Rabat and Casablanca, and is also expected to reach the Oum Er-Rabia basin further south.

These are all technological solutions that address an immediate need — the use of desalinated water to supply cities is, for example, no longer an option but a necessity — but whose effects remain uncertain in supporting the current agricultural policy. The cost of desalinated water raises concerns that its use may only be profitable for export crops. And water transfers do not take into account spatial inequalities in access to water: some rural areas, even rich in water, paradoxically suffer from water stress. This is the case in the provinces of Taounate and Sefrou, located in water-abundant areas, but where urban cuts are recurrent due to the decline of groundwater caused by illegal wells intended for irrigation, and by pollution from surrounding sand quarries.

Rainwater and rural exodus

Today, several agronomists and hydrology researchers are calling for a reevaluation of water allocations in agriculture, prioritizing the use of rainwater and so-called “bour” crops, which do not require irrigation. At stake is national food sovereignty, but also the preservation of rural jobs: in 2023, the High Commission for Planning, national statistics institute, estimated the number of people leaving rural areas for cities at 152,000 annually.

These are all warning signals that have not really been relayed at SIAM this year either. The various panels highlighted the difficulties related to water in each agricultural sector, without mentioning the responsibility of national policies in the intensive pressure on water resources. The agrodigital hub, which made its debut at the show last year, however, showcased connected farms and tractors, drones, and hydroponic crops as the very near future and potential of Moroccan agriculture.

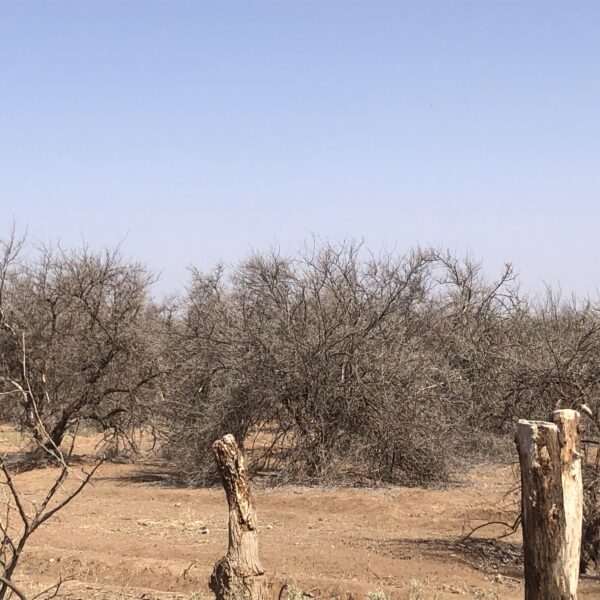

Cover photo: Burned olive trees after 6 years of drought, in the Béni Mellal region, July 2024 (Oum Er-Rabia basin) © Adèle Arusi