Once upon a time, a forgotten story or rather buried... This story took place on the Lérins Islands, off the coast of Cannes, on the Côte d’Azur. A cemetery emerged from the limbo, or rather from the underbrush and brambles that had overtaken it. In the 1970s, foresters from the National Forestry Office, which employed many harkis, repatriated Muslims, discovered a vast cemetery of more than 200 graves, left there and neglected by those who had the responsibility and charge of it.

They immediately understood, from the arrangement of the stones and the orientation of the graves, that it was a Muslim cemetery. To pay tribute to them, they had a stone engraved at the entrance of the cemetery that read: “To our Muslim brothers who died for France!” The contrast was striking, as right next to it was a well-preserved cemetery from the Crimean War, clean and very well maintained. It is true that we are, with Crimea, far from the colonial war in Algeria.

Prisoners on Ste Marguerite

What happened to find all these Muslim graves on Sainte-Marguerite Island? A story obscured, like a very large part of the forms and conditions of France's conquest of Algeria, starting in 1832. A brutal conquest that never sought to spare civilians, and sometimes even the opposite, as during the fumigations of the caves of Dahra, where they were targeted. Bugeaud, Pélissier, Cavaignac, or Saint Arnaud, these officers of the French army did not hesitate to commit real atrocities and war crimes. These facts are today well documented and established by historians, and the current controversies in France on this subject are devoid of meaning and accuracy.

The policy of confinement at the Royal Fort of Sainte Marguerite bears witness to this. This high place of state detention, once associated with the figure of the “Iron Mask” under Louis XIV, then with Protestants, continued with the detention of exiled and deported Algerians, who did not “Die for France,” as was indicated on the stone at the entrance of the cemetery, in a true historical contradiction, but rather died fighting against it, resisting the French military conquest. Indeed, part of the Smalah of Abdel Kader, this high military and spiritual figure of Algeria who led the revolt against French troops, was imprisoned at Lérins, “until further notice.” The island of Sainte Marguerite thus became, between 1841 and 1884, the main detention place for Algerians in France, deported with their families, never knowing how long they would be held prisoners outside their country and land. The letters found in the archives of the prisoners testify to the immense sadness of being cut off from their loved ones. The work of historians Sylvie Thénault, then Anissa Bouayed, who conducted a meticulous investigation in the archives at the request of the City of Cannes, which wanted to finally know the exact reality of this story, has allowed the identification of the names, including women and children, who died and were buried on the Lérins Islands. 274 people have now emerged from anonymity and oblivion, giving a face to a story that had none.

A Shared Story

The conquest war brought together populations that were not directly connected and thus profoundly changed the situation. Thus, the city of Cannes, through the policy of confinement at the Royal Fort of Sainte Marguerite, decided not by the city but by the state, found itself, unwittingly, linked to the history of colonial Algeria.

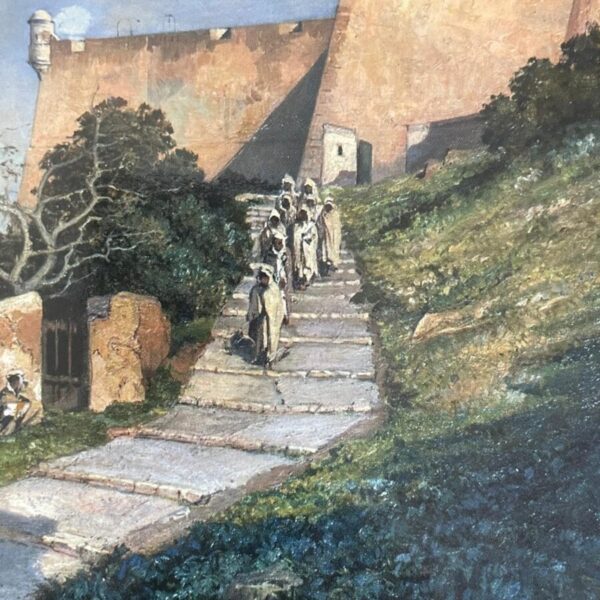

The Muslims on the island were not hidden or invisible. There indeed exists a whole series of photographs, postcards even, documents, and newspaper reports, such as L’illustration, and paintings, notably that of Ernest Buttura, which showcase this Algerian presence for over 40 years. The remarkable exhibition held in the summer of 2023 at the Museum of the Sea, by Christophe Roustan Delatour, finally brought this Franco-Algerian story out of oblivion, showing and telling what had not been shown or told. The silence and denial, persistent, have given way to a beginning of recognition of a memory that remained buried for too long. The past does not pass; attempts at erasure or temptations of forgetfulness resolve nothing; on the contrary, they foster a kind of conflicting fermentation and deepen knots of memories that could be untied to envision the future differently, between the two shores. The majestic figure of Abdel Kader, hero of Algeria, but also admired on the European side for having saved the Christians of Damascus during the uprising in 1860, could be a powerful symbolic link at a time when relations between Algeria and France are experiencing a stormy period.

Possible Horizons

A new story has begun on the Lérins Islands, with a beginning of recognition, and it should resolutely continue, despite the political and international ups and downs between Algeria and France. Everyone can find themselves in it, by emphasizing human dignity.

Men have indeed become human by burying their dead. The cemetery of Sainte Marguerite should thus be truly restored and become a place of shared memory. It is not about repentance, but an act of recognition of what has shaped our common history. A place of reflection is a place where everyone can reconnect with what elevates them.

To go further and give a face to the future, the time has come to call upon works of art; they can make visible the invisible part that haunts us. The luminous photographs of Franck Pourcel, created for the exhibition at the Museum of the Sea, form a collection that should find its rightful place in the permanent exhibition of this museum. And beyond, the project of artist Rachid Koraïchi, on the very site of the cemetery, could provide a major signal that marks the place and time of its imprint. He has already created a monument in homage to Emir Abdel Kader, once imprisoned at the Château d’Amboise, and an exemplary work in tribute to the monks of Tibhérine who were murdered in Algeria.

He has a sense of gesture, sign, and the sacred, and such a work, by an internationally renowned artist, would mark an essential step on the paths of recognition. The project is already designed; it remains to gather the means to implement it...

This path of recognition is also embodied in an excellent documentary film, made in the spring of 2025 by Laurent Boullard for France 3: “The Hidden History of Sainte Marguerite Island.” It features witnesses, actors, and specialists of this buried history, which thus comes out of the shadows, and showcases many images and documents that recount what happened on this island, off the coast of Cannes.

From this city, known worldwide for its international film festival, a place, a true link, could emerge where new pages of a common history can be written, beyond the time of discord.

Featured Photo: Painting by Ernest Buttura (1841-1920) - Muslim Prisoners on Sainte Marguerite Island (detail)