This Italian island, a forward point towards Tunisia and Africa, is known in the news for its crises and dramas, particularly related to the landings of migrants coming from the Mediterranean. It is less known that Lampedusa was long a refuge island, a “shared holy place,” between Christians and Muslims, who found there a true shelter…

Its name frequently resonates on news channels, associated with a sad string of tragedies and human distress, with a staggering tally of shipwrecks, deaths, and survivors. However, this tiny Italian territory of barely 20 square kilometers, lost somewhere between Sicily and Libya, is known superficially. It seems to emerge from a hazy past, since the moment the spotlight of current events has surrounded it. Yet, a dive into the history of this reef holds many surprises and twists. In short, there is indeed a Lampedusa before “Lampedusa,” so to speak.

Lampedusa before Lampedusa

Over the centuries, the fate of the island breathes with the water that surrounds it. As far back as one can trace, it is perceived as an important maritime crossroads, an essential node of human circulation. Since the Middle Ages, and for at least six centuries, Lampedusa has been a place in-between in a maritime space sharply divided between Christians and Muslims. Perpetually uninhabited, this rock planted in the midst of the waves enjoys a strategic position and, thanks to its neutrality, becomes an essential stop for boats, which find water, wood, and food there. Open, generous, nurturing, the island also offers the shelter of its coves to any vessel in distress during the frequent storms that strike the sea. A minuscule scar on the smooth skin of the water, Lampedusa is an empty yet central space. It is like a secret navel of the Mediterranean.

A shared sanctuary

Moreover, an astonishing symbolic device emerges here, inscribed in the long term. A small cave, hidden in the folds of the territory, hosts a unique worship. One half of this crevice is reserved for the veneration of an image of the Virgin, the other for that of a Muslim saint, whose tomb it shelters. The many sailors who stop on the island never fail to honor this small sanctuary, regardless of their religion.

The origins of this configuration are distant. When the first references surface in written sources, from the second half of the 16th century, they reveal a tradition already well established. Since then, over the decades, many witnesses regularly express their surprise at the situation they discover in the cave, where numerous offerings that Catholic and Muslim devotees have left pile up: coins, rings, pendants, diadems, candles, and more… This assortment also includes clothing and various types of utensils. Not to mention the presence of food, in the form of bread, cheese, and salted meat.

The main recipients of these provisions are runaway slaves or shipwrecked individuals, both Christians and Muslims. Thanks to these goods, they can survive while waiting for a ship to dock and take them on board: there is no need, on this deserted island, to possess the sagacity of a Robinson Crusoe to survive alone. Thanks to collective solidarity, the means necessary are available to anyone who gets lost there. In turn, passing sailors have the right to use the objects buried in the cave, but they must return them afterward or leave an equivalent of their value. According to a belief shared by all, regardless of their religion, those who violate this tacit law by wrongfully appropriating something would no longer be able to leave Lampedusa, as the wind and storm would unleash against their boats.

A place of peaceful meeting between Christians and Muslims

This island remains a space for peaceful meeting, in a sea haunted by stubborn antagonisms and belligerent clashes, where violence can erupt at any moment. With its sober and minimalist decor, Lampedusa is a contact zone, a transition, a threshold. Solitary in the open sea, it offers the experience of a limen. Landing on its shores, entering its interior, up to the cave-sanctuary, corresponds to a crossing to the elsewhere. In its landscape of sun and wind, the island allows for an intimate and soothing encounter with the other. It encourages a suspension of hostilities that extends to mutual aid between enemies.

The miracle of Lampedusa does not have designated stage directors. No ecclesiastical impresario has laid a hand on it. The sanctuary and the traditions associated with it are the result of spontaneous and anonymous creation: the work of sailors, slaves, and privateers. However, the fame of the island spreads to all corners of the sea. The Madonna of Lampedusa has its devotees in Marseille as well as in Livorno, in Tunis as well as in Tripoli.

The astonishing interreligious coexistence, permanently established on this distant island, soon becomes familiar to the cultivated public in Europe. In the 18th century, Lampedusa makes its entry into Parisian salons where the Enlightenment intelligentsia gathers. A symbol of religious openness, often referred to in a roundabout way, it seeps into the reflections of the sharpest minds of the century and slips into the pages of major authors, such as Denis Diderot or Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

This long history with fairy-tale and mythical appearances comes to an end around the mid-19th century when the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies embarks on the colonization of the island. The cave-sanctuary is then renovated, and the installations related to Muslim worship disappear. The tradition of interreligious sharing comes to an end, and the myth of Lampedusa falls asleep.

A border island

Today, once again a border island, Lampedusa reconnects with its former vocation as a place of transition and contact. It has become a limen again, but in an overcrowded space, a true bazaar of difference, where disparate and often antithetical groups coexist as best they can: migrants, tourists, local population, military, EU and UN officials, NGO staff, activists, artists... In this uncertain magma, the seeds of new practices of openness and peace can be discerned. They aim to prevent shipwrecks, rescue boats in distress, assist survivors, honor the dead, and preserve their memory as much as possible… Volunteers from afar and segments of the local population strive together to restore a bit of humanity to the border, refusing to transform the sea into a barbed-wire wall.

Lampedusa is back. Once again, as in a distant past, a collective, bottom-up elaboration converges here and shapes an open island. Once again, as in the Age of Enlightenment, Lampedusa is here to challenge European conscience.

Dionigi Albera, anthropologist, honorary research director at CNRS, is the originator of the research program on “Shared Holy Places” and Commissioner of the exhibition of the same name, a new version of which will be presented in Rome, at the Villa Medici in the fall of 2025.

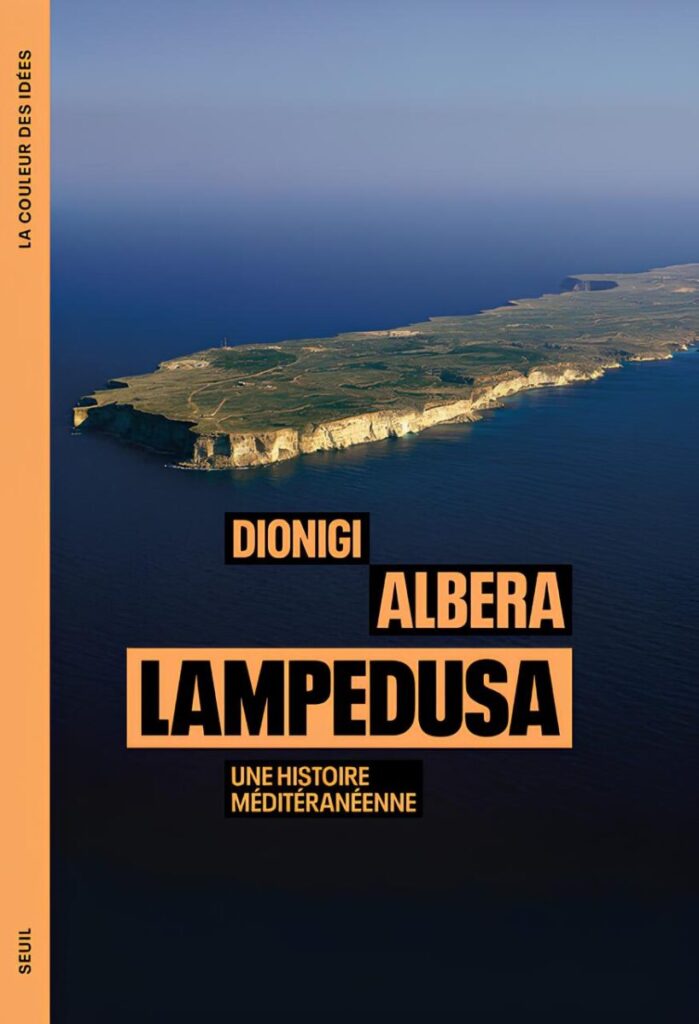

Cover Photo: The Door of Europe located at the southernmost point of the island, is a monument dedicated to migrants who died and went missing at sea ©Dionigi Albera