For a long time, too long, the Mediterranean was viewed solely as a world of the past. The quintessential place, for Europeans, of ancient heritage, of Greco-Latin sources, which according to this history were at the origin of the greatness of "our" civilization. Forgetting in the process Jerusalem and Cordoba, the Judeo-Arab sources that are an integral part of our common heritage. The time has come, in the 21st century, to move beyond such a unilateral and Eurocentric vision of the Mediterranean.

The inventions of the unknown demand

new forms.

Arthur Rimbaud

This "daddy's Mediterranean" is burdened by the weight of heritage and remains entangled in the sole ancient legacy. Such a representation of the Mediterranean is outdated; it has no place in the 21st century. It is completely out of sync and no longer corresponds to what is currently unfolding on the artistic and urban stages of the contemporary Mediterranean world.

Moving Beyond Historicism

I attempted, in the mid-1990s, to propose the hypothesis of a creative Mediterranean[1]. To try to change our perspective and representations of the Mediterranean, to finally listen to the other shores. To move beyond Euro-Mediterranean, this vertical, top-down, hegemonic vision, a projection of the North onto the South, to sketch another figure, that of a Mediterranean envisioned as a circle open to the elsewhere, where no one asserts their supremacy, artistic or cultural. A Mediterranean of equal parts[2], in a way...

This hypothesis, expressed with fragility and hope, has been confirmed. The metamorphosis has taken place in just over thirty years. The Mediterranean is no longer conjugated only in the past; it gives another face to the future. The inventions of new forms are here, before our finally opened eyes, receptive to what is coming, and no longer solely from the European world. In artistic and cultural terms, the Mediterranean world is no longer barren or dried up, imprisoned by tradition, by the repetition of the same, by past or Orientalist forms. This heavy straitjacket, a forced reverence to heritages or other canons of the past, has literally exploded. This does not mean a denial of these heritages or a simple abolition of traditional forms. Another story has begun, stemming from a movement, a momentum, a push that has allowed liberation from these obligatory forms, due to the past, or from the necessary imitation, to exist, of those from the Other, the dominant. Distinct artistic trajectories have emerged, in a form of creative jubilation, of permission to be fully oneself, or to borrow what may be just to exist fully in one’s artistic practice.

Youth of the Mediterranean

It is high time to recognize such a movement and to accompany, prolong, and showcase this creative Mediterranean, which is there, in all its effervescence.

Triumph of life, against death, war, or the grip of authoritarian and dictatorial powers? There is undoubtedly in the invention of these new forms a challenge, or a refusal to consent to the disaster, particularly political, that is present and very real. However, it is important not to forget a central fact: on the Southern and Eastern shores of the Mediterranean, societies are predominantly young. They can no longer indulge in, or be satisfied with, the sole forms of the past. They need to give birth to and sustain, in musical, visual, plastic, or literary terms, contemporary artistic expressions that resonate with their expectations.

Youth of the Mediterranean,[3] would have said the writer Gabriel Audisio, companion of the young Camus, in Algeria in the 1930s. Each generation has its challenges and its struggles. Like in the 1930s, we are facing, from one shore to the other, the rise of a nationalist, populist, and identity wave. It takes on singular forms, depending on the countries, stemming from political and religious histories and memories, in the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim worlds.

These identity regressions vehemently oppose, in the name of a reinvented tradition, or nostalgic purity, these creative forces from the Mediterranean world. They are in the alloy, in the crossing of forms and the conjunction of heritages, in the flavor of diversity, not in the nostalgia or folklore of the One, retreating into an "unexceedable," in the name of a "it was better before"...

This struggle, for it is one, lies ahead of us. No one can predict that disaster, war, fear, hatred, or even genocide will not impose themselves upon us, in the Mediterranean world, during the 2020s and 2030s of the 21st century. It is one of the paths of the possible, the worst. But the worst is never certain. "The flame of a candle," as René Char rightly wrote, in the time of resistance and occupation, inspired by the painter Georges de La Tour, remains vibrant.

A Promise and a Chance

The creative Mediterranean is a promise and a chance. It is not the result of a mere dream or an illusion. Many artists of the 21st century, who come from the Mediterranean world, are making their mark on the international scene. They express and embody all the vitality of this world, faced with immense adversity. It is neither a lost cause nor a mere passing trend.

It is a tidal wave and a momentum that seeks to find its place among exhibition spaces, concert halls or cinemas, festivals, and other contemporary scenes or seasons, which should better grasp what is coming. This is at least what we attempt to showcase and present in the "creation" section of the 22-med website. 22 countries and 11 languages to share these new forms of the creative Mediterranean...

There is at least an editorial space that is opening up and needs support, intercessors[4] to better discover and understand this Mediterranean world, in its most contemporary expressions.

It is indeed up to us not to consent to disaster, to renounce renunciation, and above all not to let ourselves be swept away by this nationalist and identity wave, which is not inevitable.

The creative Mediterranean is a vibrant source for inventing the future, strengthening our convictions, and inspiring our desires to stand tall, like that "Man who walks," by sculptor Alberto Giacometti, who has endured the worst and retains that inner strength, a secret and profound fervor, inhabited by the wonderful unknown, which keeps him standing, ready to regain his momentum.

As the contemporary poet, Renaud Ego, rightly writes:

because this spark of refusal was

all that we had left

We shared it and that sharing was a glimmer.

[1] The Creative Mediterranean, ed. Thierry Fabre, Éditions de l’Aube, 1994

[2] See Romain Bertrand, History in Equal Parts, Le Seuil, 2011

[3] Gabriel Audisio, Youth of the Mediterranean, Gallimard, 1st edition 1935, reissued in 2002

[4] Gilles Deleuze, The Intercessors, in Negotiations (1972-1990), Éditions de Minuit, 1990

Thierry Fabre

Founder of the Rencontres d’Averroès in Marseille.

Writer, researcher, and exhibition curator. He directed the journal La pensée de midi, the BLEU collection at Actes-Sud, and the programming of the Mucem. He created the Mediterranean program at the Institute of Advanced Studies of Aix-Marseille University.

He is responsible for editorial oversight.

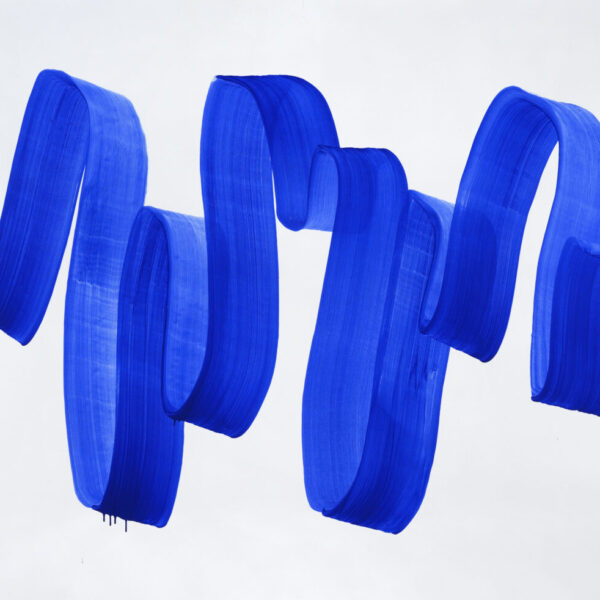

Cover Photo: Blue Wave (2016, acrylic on canvas, 160 x 200 cm) Work by Najia Mehadji presented during her exhibition My Friend the Rose at MAC VAL