From prehistory to the French colonial era, passing through the Roman, Vandal, and Islamic periods, the heritage in Algeria has not yet been fully studied. Today, the issue of protecting its historical assets is acute. This is a field in which scientists are working, using new technologies to ensure their preservation.

Algeria has a very large number of historical sites, seven of which are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Among these sites are the Casbah of Algiers, the Roman ruins of Tipaza, and the Tassili n’Ajjer considered the largest open-air museum with over 15,000 drawings and engravings dating back to 6000 BC. These sites are just a tiny part of the historical heritage scattered throughout the Algerian territory. In addition to aspects related to the research and study of these assets, the urgency today is to protect them from destruction and looting.

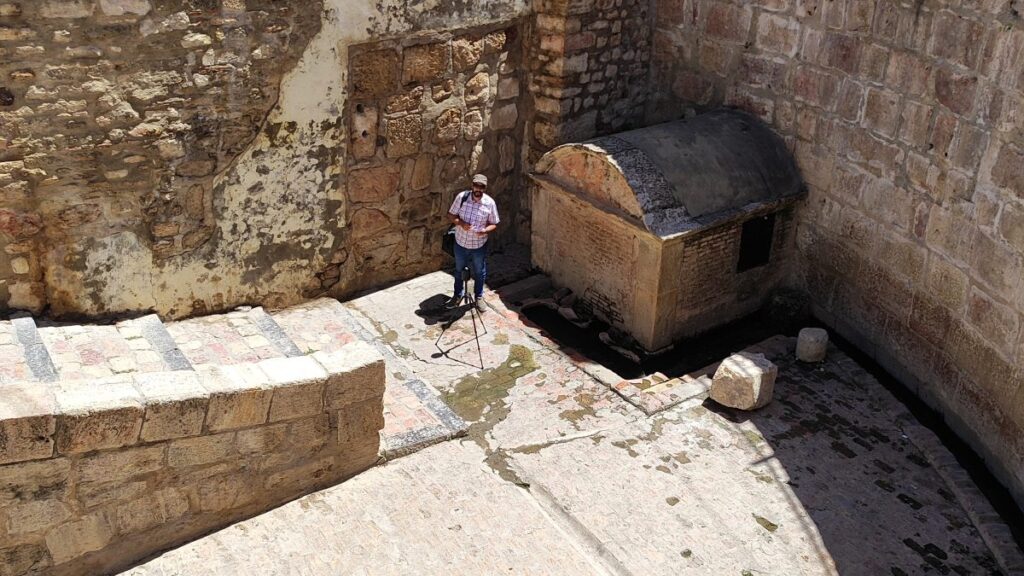

Researcher at the Center for Regional Planning Research (CRAT) in Constantine, Meriem Seghiri Bendjaballah leads a team responsible for working on the application of new technologies related to the preservation of cultural and natural heritage. Trained as an architect, her academic career is devoted to the study of historical monuments in Algeria. She is among the scientists who have realized the need to protect heritage by utilizing technological solutions. With her colleagues, she quickly moved from theory to practice. "Since its establishment in 2019, the CRAT has recruited researchers in different specialties. In terms of heritage preservation, we are required to work in a multidisciplinary framework," she explains. Architect, topographer, civil engineer, computer developer... each has a specific role. "First, we proposed a project to protect the Imedghassen (featured photo), a Numidian mausoleum dating back to antiquity. I am familiar with this site as I dedicated my doctoral thesis to it. Therefore, we created a three-dimensional model to propose the development of this historic site," highlights Meriem.

Lidar Scanner

In reality, the use of the latest technologies truly began with the arrival of Yasser Nassim Benzagouta in the team, a doctor in the art of building and urban planning, and a specialist in Building Information Modeling (BIM). His arrival coincided with the research center's acquisition of a point cloud laser scanner. An indispensable tool today, the point cloud scanner allows for a three-dimensional digitization of a space or a real object. Comprised of billions of points, this 3D acquisition is measured by photogrammetry, then transferred into a coordinate system. By increasing the density of the capture, a highly precise point cloud is obtained.

The first project of CRAT consisted of creating a virtual tour of the Palace of the Bey of Constantine. Built between 1826 and 1835 by Hadj Ahmed, the last Bey of Constantine, the site is now a museum dedicated to the Ottoman period. "This initiative also allowed us to obtain a digital twin of the palace," notes the researcher. Since this first project, CRAT has become a reference in heritage digitization. "We are not really pioneers, as there have been operations to scan historical monuments before. But the work has rarely been completed and therefore has never been exploited and shared. We recently created the digital twin of the Constantine theater, which was built in 1883, as well as scanned the Ain el bled fountain in Mila, one of the last functioning Roman fountains. Our goal is to make CRAT a specialized operator in heritage digitization," adds Meriem Seghiri Bendjaballah.

The next phase will involve using drones equipped with laser scanners to collect and analyze data over large areas.

Scanning an ancient city in 15 minutes with a drone

The CRAT collaborates notably with Fawzi Doumaz, a senior researcher and head of the Archaeo-Geomatics and Experimental Geophysics Laboratory at the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology in Rome. An engineering graduate in geotechnics from the University of Houari-Boumediene in Algiers, he worked at the Center for Research in Astronomy, Astrophysics, and Geophysics (CRAAG). In the mid-1990s, he settled in Italy where he conducts various works, particularly using geomatics. This specialty encompasses all computer techniques applied to earth sciences and archaeology for heritage preservation actions. "I entered the field of archaeology through geomatics. Being a licensed drone pilot allows me to ensure the entire production chain, from data acquisition to processing. I use a drone equipped with a Lidar scanner with infrared lasers that allows for very high-density scans. A 15-minute flight can cover a significant area. We have a scientific project to conduct aerial surveys in Lambèse, the last capital of Numidia during the Roman era," explains Fawzi Doumaz.

According to the scientist, the interest in digitizing heritage aims to obtain an exact copy of the sites, as well as their dimensions. "The point cloud laser scanner also allows quickly obtaining direct structural information that is difficult to obtain with old techniques. This is the case with wall thicknesses, the nature of construction or restoration materials, as well as the presence of micro-fractures. The overall plan can be visualized through the digital twin."

Awareness

Fawzi Doumaz believes that in Algeria, there is indeed a growing awareness of the need to use new technologies for the protection of heritage. "The task is enormous given the number and diversity of sites and monuments. In Algeria, it only takes digging with a fork to make archaeological discoveries. But above all, it is necessary to protect all these historical assets from theft, vandalism, and even climate change. Therefore, it is essential to move from awareness to decision-making to initiate digitization programs and site delineations. This willingness, once affirmed, should start with an assessment. The technology is there, it just needs to be used." For him, it is a real race against time. Things are changing within the public authorities, with the State being responsible for the management and protection of historical cultural assets. This year, the theme of the heritage month chosen by the Ministry of Culture was precisely: "Cultural heritage and risk management in the face of crises and natural disasters."