The Mediterranean is a representative space of migrations in the world. This subject, publicized and politicized, is the subject of simplification and commonplaces at the very moment when, for the past thirty years, it has been becoming more complex and diverse.

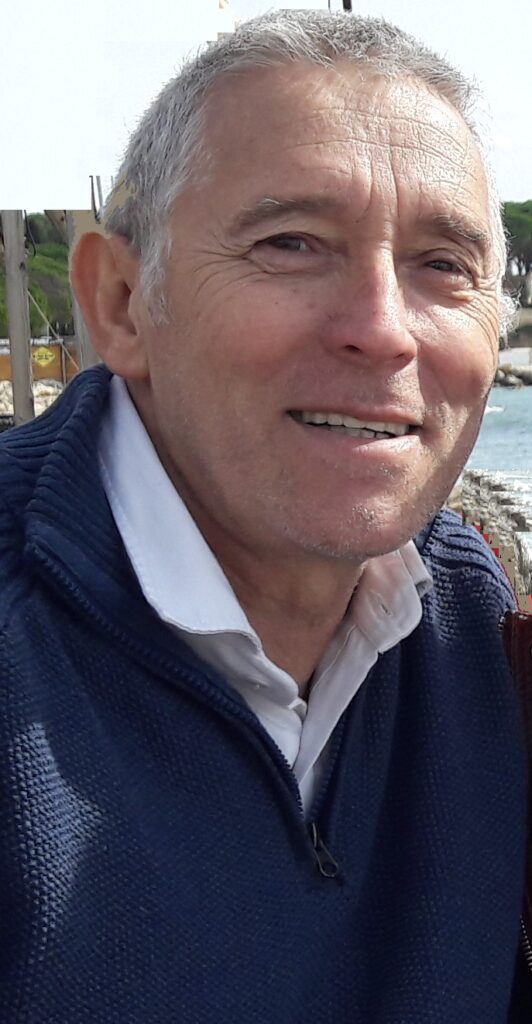

It is at the heart of this dialogue between Bernard Mossé, scientific manager of NEEDE Méditerranée, and Andrea Calabretta, a sociologist specializing in migrations around the world, in the Mediterranean, and particularly in Italy. This helps to better understand this specific issue.

To be continued over five weeks.

# 2 - Faced with the increasing complexity of categories and motivations of migration actors, social sciences have had to adapt their analytical tools.

Bernard Mossé: You said that sociologists' categories do not always align with administrative categories. Can you give us an example of administrative categories that are reworked by sociologists? And it's also an opportunity for me to ask you, in the face of these changes, how sociology and social sciences in general have evolved in their analysis.

Andrea Calabretta: Yes, of course. It's an epistemological question: we, sociologists, as workers in the social sciences, as well analyzed by P. Bourdieu, are pushed to use and think in common sense and state categories. We undergo this pressure from normative, legal categories, as if they were objective, which is not the case: these are socially created categories. For example, there is no "human" difference between an asylum seeker and a migrant worker. We are called to work on and with people who are categorized like that by the state, and this categorization changes their lives. It is evident that this categorization has objective effects on people's lives. But our work also involves deconstructing these supposedly "natural" categories. That's why I am a big fan of the sociologist A. Sayad. Since the 1970s, he has led us to think about migration beyond state categories. Thanks to him, we know that all labor migration is also family migration. These categorizations exist, but the sociologist must be careful not to normalize or naturalize them. This is still my perspective today: in migration studies, there is a risk of being analytical, of letting institutions indicate what should be studied and how to name things. The big risk is not empowering oneself to name research objects, because that is really the basis of our work.

To address your second question, I believe that the sociology of migratory phenomena has evolved in recent years: we have learned to work within complexity. It took some time because until the 1980s, or even the 1990s, we still had rather simplistic interpretations. There has been a whole process of considering complexity and also the incorporation of decolonial thinking.

Bernard: Is it reductive to characterize this evolution of research by the fact that with A. Sayad, a collaborator of P. Bourdieu, we were able to consider the migrant as neither from here nor from there, in the wake of decolonization, and that today the migrant is considered both from here and from there, particularly through transnational analysis?

Andrea: In my opinion, it's a bit reductionist, yes. Because in Sayad's works, we don't only have absence. There is also the whole question related to presence, the permanence in France of migrants, especially Algerians, which results in intergenerational trajectories in the immigration country.

In fact, today as yesterday, in the 1970s, these two poles dialogue in the life of the migrant: presence and absence. Even though there are changes that recompose them. For example, mobile phones and social networks now allow for maintaining a social relationship in a broad, communicative, symbolic sense. But it would be simplistic to speak of a "double presence."

Sometimes, despite more powerful analytical tools, the researcher is led to simplify their discourse, to respond bluntly to complex phenomena. This is particularly the case in responses to research programs of large international organizations and to requests from political decision-makers. This is somewhat the risk that I see in the sociology of migrations today: the simplification of complexity, to meet the needs of the research "market."

Bernard: Maybe you also think it is too simplistic to say that the sociology of the 1970s considered the migrant as someone enduring their fate, whereas today it sees them more as an actor?

Andrea: No, this is not a simplification. I think indeed, as I said, the 1990s represent a change in the imagination of migrations. Today, there are tools, individual, identity-related, that lead migrants to move not only from one country to another, but within the social world, differently than in the past. The self-image of the migrant allows them to consider themselves more as actors than mere participants in a host society in search of workers. I agree with this process of building more active actors in migration.

Although there is sometimes a somewhat overly optimistic and oversimplified sociological reading on this aspect.

Biographies

Andrea CALABRETTA is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Padua (Italy), where he teaches courses on qualitative research methods in sociology. He completed his Ph.D. in 2023 with a thesis on transnational relations between the Tunisian community in Italy and the country of origin, based on the mobilization of Pierre Bourdieu's theories. In addition to relations with the country of origin, he has worked on the processes of social inclusion and exclusion that affect migrants and their descendants, their work trajectories in Italian society, and the processes of identity construction of migrants.

Bernard Mossé Historian, Head of Research, Education, and Training at the NEEDE Mediterranean association. Member of the Scientific Council of the Camp des Milles Foundation - Memory and Education, for which he was the scientific director and coordinator of the UNESCO Chair "Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences, and Convergence of Memories" (Aix-Marseille University / Camp des Milles).

Bibliography Appadurai Arjun (2001), After Colonialism: Cultural Consequences of Globalization, Paris: Payot.

Bourdieu Pierre, Wacquant Loïc (1992), Responses. For a Reflexive Anthropology. Paris: Seuil.

Calabretta Andrea (2023), Accept and Fight Stigmatization. The Difficult Construction of the Social Identity of the Tunisian Community in Modena (Italy), Territoires contemporains, 19. http://tristan.u-bourgogne.fr/CGC/publications/Espaces-Territoires/Andrea_Calabretta.html

Calabretta Andrea (2024), Double Absences, Double Presences. Social capital as a key to understanding transnationality, In A. Calabretta (ed.), Mobilities and Trans-Mediterranean Migrations. An Italian-French dialogue on movements within and beyond the Mediterranean (pp. 137-150). Padova: Padova University Press. https://www.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/download-count/attachments/2024-03/9788869383960.pdf

Castles Stephen, De Haas Hein, and Miller Mark J. (2005 [latest edition 2020]), The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, New York: Guilford Press.

Hein de Haas (2024), “The idea of large waves of climate migrations is highly unlikely”, article in 'L’Express'. https://www.lexpress.fr/idees-et-debats/hein-de-haas-lidee-de-grandes-vagues-de-migrations-climatiques-est-tres-improbable-K3BQA6QEKRB2JCN4W47VTNCA2Y/

Elias Norbert (1987), The Retreat of Sociologists into the Present, Theory, Culture & Society, 4(2-3), 223-247. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/026327687004002003

Elias Norbert, and Scotson John L. (1965 [reprint 1994]), The established and the outsiders. A Sociological Enquiry into Community Problems. London: Sage.

Fukuyama Francis (1989), “The End of History?” The National Interest, 16, 3–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184

Mezzadra Sandro, Neilson Brett (2013), Border as Method, Durham: Duke University Press. https://academic.oup.com/migration/article-abstract/4/2/273/2413380?login=false

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), The Double Absence: From the Illusions of the Emigrant to the Sufferings of the Immigrant. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), Immigration and "State Thinking". Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 129, 5-14. https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1999_num_129_1_3299 Simmel Georg (1908 [reprint 2019]), The Stranger, Paris

From this conversation, the AI has generated a flow of illustrations. Stefan Muntaner fed it with editorial data and guided the aesthetic dimension. Each illustration thus becomes a unique work of art through an NFT.