The Mediterranean is a representative space of migrations in the world. This subject, publicized and politicized, is the object of simplification and commonplaces at the very moment when, for about thirty years, it becomes more complex and diverse.

It is at the heart of this dialogue between Bernard Mossé, scientific director of NEEDE Mediterranean, and Andrea Calabretta, a sociologist specializing in migrations worldwide, in the Mediterranean and in Italy in particular. This helps to better understand this specific issue.

To be continued over five weeks.

#1 The world we live in has been built by migrations

Bernard Mossé: Dear Andrea, would you like to introduce yourself?

Andrea Calabretta: I am a social sciences researcher at the University of Padua in Italy where I conducted my doctoral research. I have worked on transnational relations, particularly on the Tunisian community in Italy, specifically those living in Modena in northern Italy and in Ragusa, Sicily. They maintain relations with the country of origin on various levels: economic, symbolic, and identity.

After obtaining my Ph.D., I took part in a research project in Milan on the working conditions of several immigrant communities in the city. Now, I am working in Padua on a research project about the second generation in Italy: the children of migration, especially of Maghrebi origin, who are transitioning into adulthood, often in search of employment. How do they grow up in Italy, what are their living conditions, their integration into the workforce, housing issues: how do these children of migrants enter adulthood and experience their participation in Italian citizenship.

I have published works in English, French, and Italian on these issues: the relationship with the home country and the social exclusion of migrants. These are the two main aspects of my current research.

Bernard: Can you give us a general overview of migrations around the world and the evolution of sociology itself in relation to migrations?

Andrea: I think it is important to start with an observation: throughout human history, there is an obvious continuity of migratory phenomena. It is important for me to emphasize this because it allows us, especially as researchers, to step back from the pressure of current events: as sociologist Norbert Elias says, this pressure sometimes makes us lose sight of the bigger picture.

It is necessary to understand that the world we live in has been built by migrations. I was born in Rome, the Eternal City, which was founded, according to legend, by the descendants of Aeneas, a prince who left Troy in Anatolia: Aeneas is a sort of asylum seeker, if we can say that in today's terms!

Bernard: With his wife, his son, his friends, and his father Anchise on his back...!

Andrea: That's it. The history of the world is marked by migrations and by a certain permanence of this phenomenon. To stick to the Italian case and return to the contemporary period, Italy has been disrupted by migrations: it is estimated that in a century, between 1876 and 1988, 27 million Italians left for abroad: it's almost half of the population of Italy today. These are huge numbers that have changed the human and social landscape of the country. At a time, the 19th century, when the societies of Europe, America, and Oceania were reconfigured by the migratory movement.

This is to talk about the continuities and the importance of migratory phenomena. And it is the basis of the analysis: these movements of people transform both the societies of origin and the societies of arrival. It is a recurring social phenomenon: we have locals who already know each other, who have a certain social power, and newcomers who lack resources.

There is also the constant question of the temporality of migration. This is what Georg Simmel tells us: the stranger is the one who remains tomorrow. One cannot speak of migration without considering the temporality of these movements.

There is also the question of space. Not only movement in geographical space, but also movement in social space and symbolic space.

In these vast continuities, it is not simple to determine discontinuities. But in recent history, I think we can identify a moment of discontinuity in the 1990s, because it is a time when we witness the collapse of the communist model, a political renewal in the world, a new imaginary being created, related to communication, means of transportation. There is truly what the Indian anthropologist Arjun Appadurai thinks in terms of new "landscapes," a historical set of different mutating collective actors: nation-states, transnational societies, diasporic communities, sub-national groups and movements, and even more intimate ones such as villages, neighborhoods, and families, what he calls ethnoscapes...

These new imaginary worlds are crossed by people in motion: not only migrants, but also other figures (entrepreneurs, tourists, pilgrims, etc.) who, in their movement, interact with other movements, sometimes antagonistic: financial, communicative, and media movements.

One can think that from the 1990s, the typical characteristics of migration remain, but they apply and take place in a different social context. This is what is referred to in terms of "globalization", even though it is a term that I don't like very much. Nevertheless, we can say that migrations are part of a global society that is much more interconnected, and are part of an imaginary that has shifted.

Bernard: Excuse me, just a parenthesis; what is the reason for this reluctance to use the term globalization? Is it because globalization also involves regionalization for you?

Andrea: My reluctance is related to the fact that it is a term with a more political than scientific dimension, like many other terms used in sociology, including those I use myself, such as integration, transnationalism... The term globalization developed, especially in the 1990s, with a political dimension as a synonym for a very positive future of the neoliberal global society.

This political imaginary induces the idea that we will live in a world without history, as Francis Fukuyama said. And obviously, that is not the direction we are heading towards.

So, in relation to these new landscapes that are developing in the 1990s, I believe that to characterize the current migratory phenomenon, we can refer to the analyses of the well-known book The Age of Migration by sociologists S. Castles, H. De Haas, and M. J. Miller (2005), which can be summarized by the notion of complexification.

The real key to understanding current migrations is to think of them as a complex phenomenon, much more complex than what we have learned to know before.

First, the globalization of migrations. More and more countries are involved in international migration flows. Regions of the world that were spared are now right in the middle of general human movements and are key players as countries of origin and as destination countries.

A change in the directions of migratory flows. South-South flows have become more prevalent compared to South-North flows. Regions have become new migration hubs: for example, the Persian Gulf is a new arrival region.

An internal differentiation of the phenomenon and its motivations. Categories from the past are no longer valid: people on the move are no longer just factory workers or part of family reunification, but there is a proliferation of figures and paths. Transit migrations are becoming longer and more substantial.

A feminization of immigrant labor: that is a question that will be central in the coming years in Europe, especially with our aging societies, and the care work which is predominantly done by women.

These trends are in dialogue with each other.

Finally, in the midst of these upheavals, the most important thing is the increasing politicization of the migration issue. There were the European elections last June: we saw that it was practically impossible to conduct an election campaign without addressing migration.

In this sense, the objective complexification of migratory movements is closely linked to their politicization and the invocation of a tightening of the rules.

On one hand, there is a push to close the borders, on the other hand, efforts are made to make the living conditions of migrants increasingly harsh. As a result, transit routes are becoming longer and more challenging.

Countries of emigration or transit become countries of immigration because people are forced to stay there for years. This is the case, for example, of Turkey.

This is pretty much the image you need to have: an image of complexification accompanied by politicization, meaning in this case the criminalization of migrants, not only in Europe: it's the same thing almost everywhere, like in America, between the United States and Mexico.

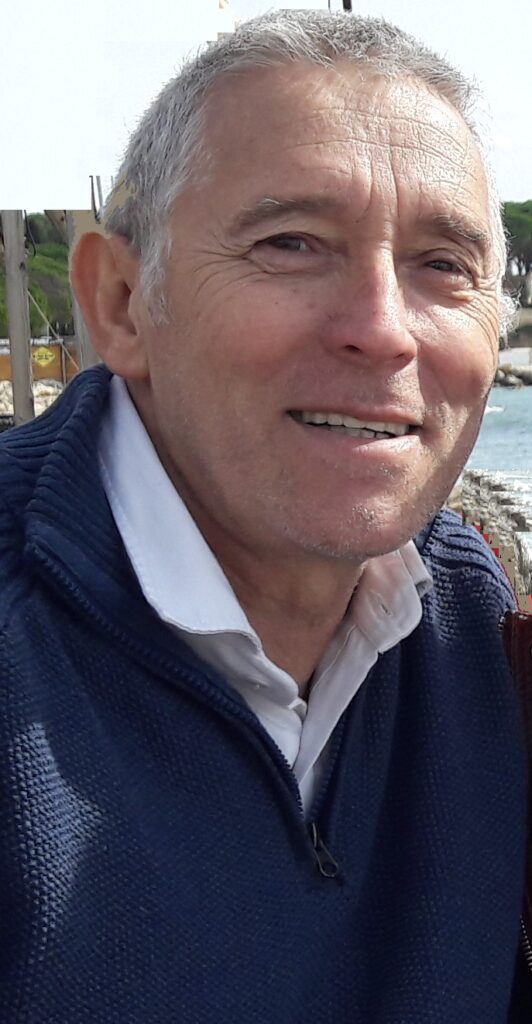

Biography

Andrea CALABRETTA is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Padua (Italy), where he teaches courses on qualitative research methods in sociology. He completed his Ph.D. in 2023 with a thesis on transnational relations between the Tunisian community in Italy and the country of origin, based on the mobilization of Pierre Bourdieu's theories. In addition to relations with the country of origin, he has worked on the processes of social inclusion and exclusion that affect migrants and their descendants, their work paths in Italian society, and the processes of identity construction of migrants.

Bernard Mossé Historian, Research, Education, and Training Manager of the NEEDE Mediterranean association. Member of the Scientific Council of the Camp des Milles Foundation - Memory and Education, for which he was the scientific manager and coordinator of the UNESCO Chair "Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences, and Convergence of Memories" (Aix-Marseille University / Camp des Milles).

Bibliography Appadurai Arjun (2001), After Colonialism: Cultural Consequences of Globalization, Paris: Payot.

Bourdieu Pierre, Wacquant Loïc (1992), Responses. For a Reflexive Anthropology. Paris: Seuil.

Calabretta Andrea (2023), Accept and combat stigmatization. The challenging construction of the social identity of the Tunisian community in Modena (Italy), Territoires contemporains, 19. http://tristan.u-bourgogne.fr/CGC/publications/Espaces-Territoires/Andrea_Calabretta.html

Calabretta Andrea (2024), Double absences, double presences. Social capital as a key to understanding transnationality, In A. Calabretta (ed.), Mobilities and trans-Mediterranean migrations. An Italian-French dialogue on movements in and beyond the Mediterranean (pp. 137-150). Padova: Padova University Press. https://www.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/download-count/attachments/2024-03/9788869383960.pdf

Castles Stephen, De Haas Hein, and Miller Mark J. (2005, last edition 2020), The age of migration. International Population Movements in the Modern World, New York: Guilford Press.

de Haas Hein (2024), "The idea of large waves of climate migrations is highly unlikely," article in ‘L’Express’. https://www.lexpress.fr/idees-et-debats/hein-de-haas-lidee-de-grandes-vagues-de-migrations-climatiques-est-tres-improbable-K3BQA6QEKRB2JCN4W47VTNCA2Y/

Elias Norbert (1987), The Retreat of Sociologists into the Present, Theory, Culture & Society, 4(2-3), 223-247. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/026327687004002003

Elias Norbert, and Scotson John L. (1965 [reprint 1994]), The established and the outsiders. A Sociological Enquiry into Community Problems. London: Sage.

Fukuyama Francis (1989), “The End of History?” The National Interest, 16, 3–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184

Mezzadra Sandro, Neilson Brett (2013), Border as Method, Durham: Duke University Press. https://academic.oup.com/migration/article-abstract/4/2/273/2413380?login=false

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), The Double Absence: From the Illusions of the Emigrant to the Sufferings of the Immigrant. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), Immigration and "State Thinking". Acts of Research in Social Sciences, 129, 5-14. https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1999_num_129_1_3299 Simmel Georg (1908 [reissue 2019]), The Stranger, Paris

From this conversation, the AI has generated a flow of illustrations. Stefan Muntaner fed it with editorial data and guided the aesthetic dimension. Each illustration thus becomes a unique work of art through an NFT.