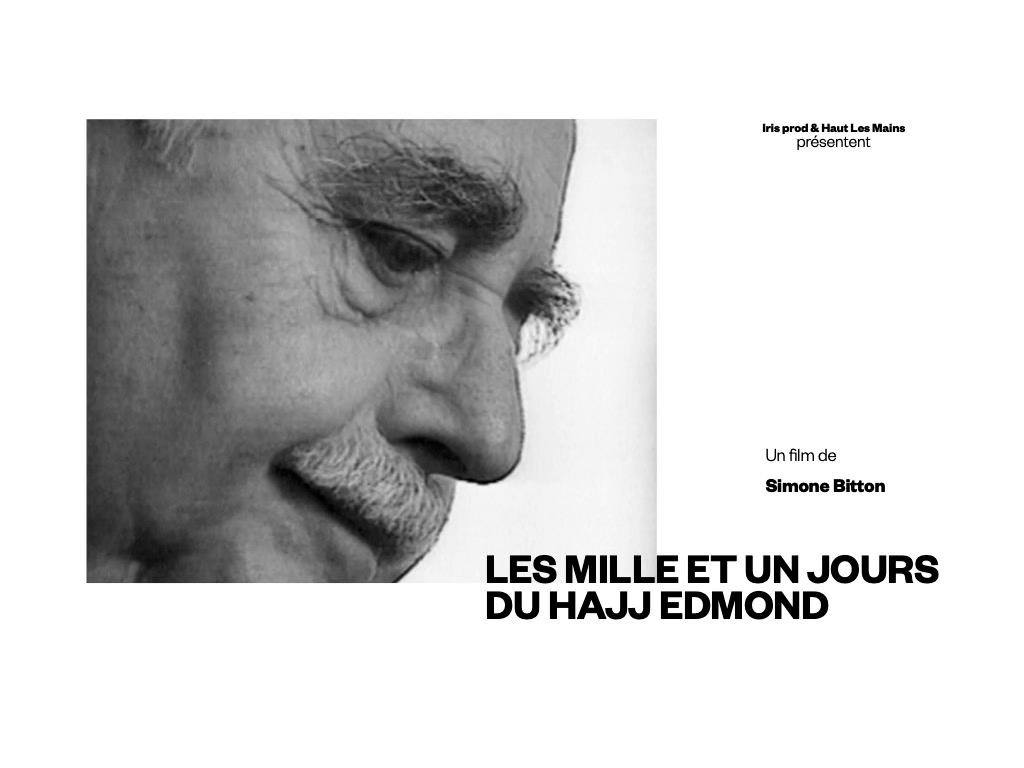

Edmond Amran El Maleh, known as "the Moroccan Joyce," has been gone for almost fifteen years. Simone Bitton, who identifies with his ethical and aesthetic radicalism, in the face of Zionism and for an uncompromising allegorical art, dedicates a documentary film to him, with both precision and evocative strength, The Thousand and One Days of Hajj Edmond. She portrays a plural writer and a being who is both singular, uncompromising, and welcoming.

As a sculptor of words and images, Simone Bitton chose, in the documentary film she has dedicated to the writer Edmond Amran El Maleh (1917-2010), to adopt an epistolary tone in the second person, echoing the cultural attribute given to him by his friends in Rabat, Asilah, Paris, Essaouira, or Beni Mellal, of Hajj. This mixed, displaced nickname, Hajj Edmond, which serves as the title of the film, removed any suspicion of strangeness in relation to a syncretic nation, woven from Islam, Judaism, and other forms of popular spirituality, and highlighted his figure as an affable, respected man. In one of his declarations recorded in the magazine Les temps modernes, he referred to himself as "Moroccan Jew" (non-Jewish Moroccan), emphasizing the preeminence of his land over his allegiance. He thus indicated his identity sidestep, his fusion relationship with his community of destiny, his art of delicately weaving the different threads that connected him to his locality, and consequently, his wish for a decentralized humanism.

Moroccan Jew

The Thousand and One Days of Hajj Edmond. The film encapsulates the original drama of exile orchestrated from the mid-1950s, overnight by the Jewish Agency with the complicity of Moroccan authorities, of Judeo-Amazigh populations, sedentary for over two thousand years, and the melancholic, allegorical evocation made by the author in Parcours immobile (Maspero, 1980), and later in Mille ans un jour (Pensée sauvage, 1986). The grave of Nahon, designated as the last Jew buried in Asilah, is seized by the author, as he publishes his first novel at sixty-three, to signify "the emblematic death of a community and its rooting in this land." It is not only for the plundered Palestine that this writer, radically opposed to Israeli colonial policy, resents Zionism, but much more fundamentally for having impoverished, stripped his native Morocco, like other Arab nations, of its millennial plurality.

When Simone Bitton, still young, an apprentice filmmaker who fled Israel in the late 1970s, met him in Paris, where he had exiled since 1965, he questioned her at length about the living conditions of Sephardim there. His secret, utopian dream was that they would feel cramped and decide to return to their true country, Morocco. Unbeknownst to her, she later transformed into an investigative character in his literary texts. And he populated his novels, in a Joycean sap, with resonances, scents, sounds, and vernacular words, which express both the melancholy of loss and the poetics of attachment.

A Flourishing Life

Like Marcel Proust, he was for a long time, young in Safi and then in Casablanca, during the 20s and 30s, horrifically asthmatic, frail, confined to the family home. When he took up his pen to write about his existential pain decades later, he spoke of "the birth of a wise young man who dreamed of becoming a breeder of words."

His sentences do not seek to testify to the world, but to create one, a receptacle for shards of lives irreducible to an autobiography. Sensitive to his flourishing universe, Simone Bitton has peppered her film with sequences that tell parts of his life and fixed shots that invite, like in a rhizome, to traverse the countless arteries drawn by his writings. And since the urgency he felt was as much ethical as aesthetic, she has well redrawn his singular trajectory, from resistance and communism, which proved exhausting due to Stalinism, but indispensable for his values, to the workshops of unclassifiable painter-artists (Ahmed Cherkaoui, Khalil Ghrib, Hassan Bourkia ...) whom he loved for their attentiveness to the ephemeral and the unsurpassable.

From beginning to end, she reconstructs an abundance of love, first for his partner, Marie Cécile Dufour, initially known in Casablanca, where they both taught philosophy before exile. She long served him almost as a metronome in his life. A specialist in Walter Benjamin, her lookalike, she joked that they had a ménage à trois with him. Not very talkative, she watched over with firm kindness the coherence of his universe, the strength of his texts and their right to opacity, to take him with her to her parents' mill in Burgundy, and to regularly drive back with him, ten years after exile, every summer, to his beloved Morocco.

In their small apartment at 114 Bd Montparnasse in Paris, for over thirty years, she had her weaving loom and he had his cupboard that served as a kitchen to prepare his spicy dishes, and around them an endless ballet of friends, where Morocco, Palestine, Lebanon, philosophy, political debates, hearty laughter, and the feeling of always being welcomed by a loving couple longing for children intersected. In their home, sensitive beings to the world's repressions and dramas gathered informally and often discussed them with radical humanity.

In the film, Mohamed Tozy, Dominique Eddé, Leila Shahid, Réda Benjelloun, and Abderrahim Yamou take turns recounting or reading episodes from this good life, the nuances of a battered political consciousness, but at the same time the echoes of a significant literary voice. Hajj Edmond never succumbed to the sirens of Parisian salons nor to the chandeliers of a deceptive Francophonie. His attachment, in addition to his land, is to his mother tongue, to the roughness of the sounds that traverse the written text to give it a sap and a memorial density. And once back home, after Marie Cécile's departure, encouraged by his friend the writer Mohamed Berrada, there would be another circle in his new home in Agdal, Rabat, from the year 1999 until his passing.

The Figure of Hajj Edmond

The title Hajj Edmond then takes on its full meaning, as this is how ordinary people call him at home. But beyond the act of deference, it seals the strength of a deep friendship with people from all walks of life, who adopt him as one of their own. L'kbira, the woman who looked after him and whose gastronomy he praised, spontaneously states in the film: "he was a Muslim Jew." In the mausoleum, symbolically erected in his likeness at the Maqam, this syncretism, which underscores his attachment to a mixed, ancestral spirituality, is spatially translated. Just as, in the wake of his death on November 15, 2010, his burial in the Jewish cemetery of Essaouira, reopened for the occasion, symbolically refers to that of Asilah where he fictionally situated Nahon, the last Jew buried.

The filming of the documentary was almost completed before October 7, 2023, but its editing was carried out throughout this unbearable genocidal period. Simone Bitton says she held on because, in the face of disaster, this was a debt. Edmond Amran El Maleh was one of those rare Arab Jews, inconsolable over the political abduction carried out in Morocco, as in Algeria, Tunisia, or Iraq, on the ruins of Nazism, as he was uncompromising on the rights of Palestinians to their state and their legitimate return. He was not so as a political activist or a producer of conventional discourses, but rather as a weaver of narratives, an evoker of memories, and an insatiable breeder of precise words.

Driss Ksikes is a writer, playwright, media and culture researcher, and associate dean for research and academic innovation at HEM (private university in Morocco).