Education faces growing access inequalities, but also new possibilities offered by digital technology and artificial intelligence. In several Mediterranean countries, teachers, communities, and associative actors are testing or implementing tools to adapt learning, strengthen inclusion, and transmit technological skills.

During the holiday season, 22-med juxtaposes and contextualizes solutions that have been the subject of articles in the French media Marcelle with articles on the same theme published in 22-med.

When digital technology facilitates school learning

Summary of the article by journalist Audrey Savournin, published in Marcelle on September 8, 2025

Digital technology is gradually establishing itself as a support for school learning, particularly for students facing difficulties. Enhanced libraries and three-dimensional visualization tools allow for content adaptation, diversification of pedagogical approaches, and support for inclusion. Through two systems tested in schools, the enhanced library Sondo and the 3D model catalog Foxar, teachers and communities are testing uses that are still unevenly adopted.

Learning to read, to understand a text, or to navigate in space relies on progressive acquisitions. For some students, these learnings are weakened by cognitive or attention disorders. In the face of these difficulties, teachers are looking for tools capable of complementing traditional practices. Educational digital technology is now part of this search for solutions, encouraged by national and international public policies.

Digital technology as a lever for inclusive education

Nearly one in five children over the age of five faces school difficulties, according to data from the French Society of Pediatrics. Dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, attention disorders, or intellectual precocity affect, on average, one student per class. For teachers, supporting this diversity represents a daily challenge.

A study reported by Canopé in 2022 shows that more than eight out of ten teachers believe they encounter obstacles to inclusion. Digital technology then appears as a possible support. Researchers in education sciences highlight its potential to evolve pedagogical practices and improve the schooling of all students, provided that the tools are designed for real use in the classroom.

Some communities are seizing this opportunity. In Marseille, the municipality has been offering free licenses to several schools since the start of the 2023 school year to experiment with two educational applications, Sondo and Foxar. This gradual deployment is based on work conducted with the National Education and aims to equip willing establishments, from primary to secondary education.

Sondo, reading differently to understand better

Sondo presents itself as a digital library of enriched works. It allows for the adaptation of text display to the needs of each student. Adjustable font size, colored syllables, accessible definitions, paragraph masking, or audio listening facilitate decoding and understanding.

The tool was designed to promote autonomy. The student chooses the features that are useful to them, on a computer, tablet, or phone. Teachers can also use it collectively on an interactive digital screen. Originally designed for dyslexic students, the platform remains accessible to all, avoiding any stigmatization.

With six hundred works of children's literature, both classic and contemporary, adapted to the curricula from CP to terminale, Sondo currently reaches several hundred thousand students. It is particularly used in Ulis and Segpa programs, but also by allophone or visually impaired students. Home access allows for extending school work outside of class.

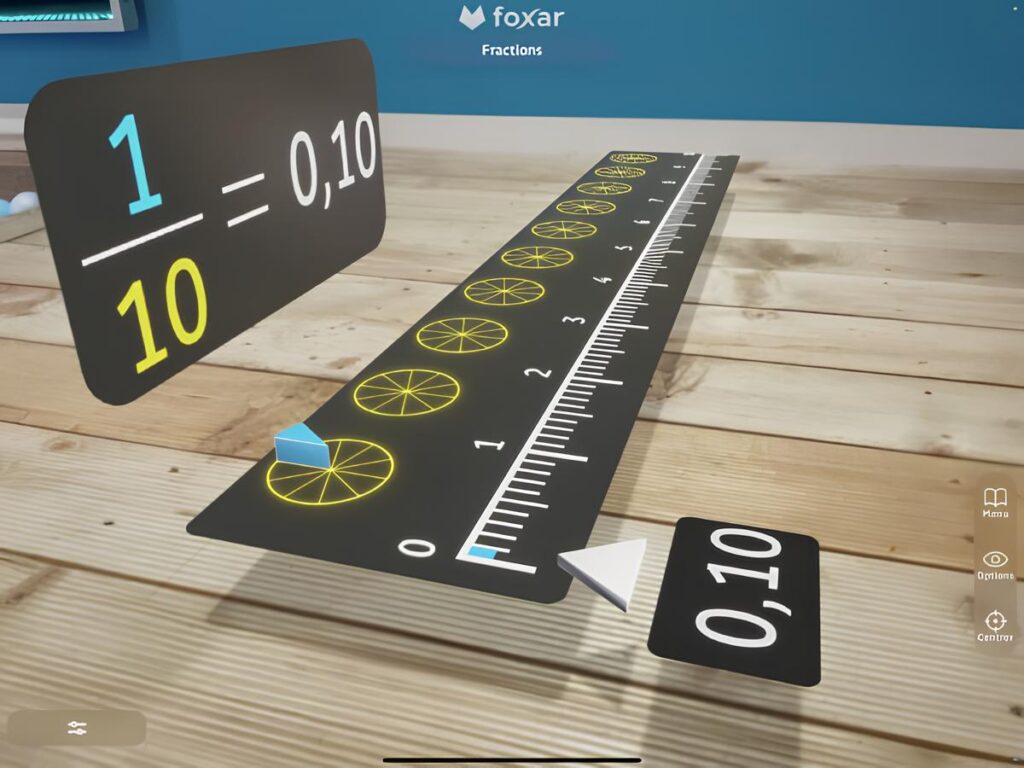

Foxar, visualizing to learn

Foxar is based on a different principle. The application offers a catalog of three-dimensional models to explore in augmented reality. Students can observe objects or phenomena from different angles, moving around the projection displayed on the tablet.

Developed in collaboration with cognitive psychology laboratories and the National Education, Foxar aims to make abstract concepts from the school curriculum concrete. Mathematics, science, history, or geography are approached through interactive models, complemented by written explanations and soon audio.

The tool is particularly aimed at students with visual memory or those who struggle to stay focused during lectures. Since its creation, the application has been downloaded several hundred thousand times and used in many establishments, from primary to high school. The communities that have tested it have mostly chosen to continue its use.

Despite these positive feedbacks, the adoption of educational digital technology remains uneven. Researchers still observe cautious uses, sometimes limited to occasional experiments. The challenge now lies in the sustainable appropriation of these tools by teachers, so that they become true universal pedagogical supports and not just occasional supplements.

In a refugee camp, children learn to code

Summary of the article by journalist Monjed Jadou published in 22-med on September 3, 2025

In the Dheisheh refugee camp, near Bethlehem, a local initiative opens up unprecedented access to coding, robotics, and artificial intelligence for children. Created by camp residents, the Rails Academy allows young Palestinians to acquire technological skills absent from traditional school curricula and to envision a digital future.

In schools managed by UNRWA, the education provided remains focused on core subjects. New technologies and artificial intelligence are largely absent. In light of this observation, young innovators from the camp decided to create an alternative learning space capable of meeting the aspirations of children attracted to digital tools but deprived of access to appropriate training.

Robotics workshops at the heart of the camp

At the Rails Academy, children discover robotics through hands-on exercises. Educational robots, solar panels, or rovers inspired by space missions serve as pedagogical supports. Students simulate, for example, Martian expeditions, manage resources, or program miniature drones. These activities connect coding learning to playful and collaborative situations.

At twelve years old, Mustafa Mohammed is among the most engaged students. He learns to program with age-appropriate tools and to assemble different robotic components. He now masters the use of sensors, color recognition, and the design of structures capable of overcoming obstacles. The academy offers him a first contact with skills he would not have been able to acquire in a traditional school setting.

Through the workshops, children develop their autonomy and problem-solving abilities. They learn to work in teams, test solutions, and correct their mistakes. For many, it is also a space where technological imagination can express itself freely, away from the constraints of daily life in the camp.

A community initiative supported by families

The Rails Academy was born from the commitment of fathers and community activists. Noticing the natural interest of children in technology and the lack of accessible offerings, they decided to create their own structure. Supported by the camp's popular committee and local institutions, the academy now welcomes around a hundred children aged five to nineteen.

Volunteers have set up three laboratories with limited resources. Despite high demand, many children remain on waiting lists due to insufficient resources. Summer programs combining games and technical learning complement the offering to maintain an educational link throughout the year.

The academy's leaders emphasize the importance of transforming children's relationship with technology. The goal is not only to consume digital tools but to understand how they work and to become capable of creating. This approach aims to strengthen the confidence of young people and broaden their professional perspectives.

Training a connected youth despite resource shortages

The Rails Academy aligns with the United Nations' sustainable development goals, particularly by promoting environmentally friendly technology. Several teams of students are preparing to participate in international robotics competitions, following national selections organized at Birzeit University. These events offer strong symbolic recognition and open children to exchanges beyond borders.

However, material constraints remain significant. The lack of computers, equipment, and funding hinders the project's expansion. One computer may be shared by many students, forcing supervisors to be ingenious in maintaining the quality of the workshops.

Despite these obstacles, the dynamic initiated is gradually transforming children's views of their future. By learning to code and design robots, they develop the ability to think differently and to imagine new solutions. For the founders of the academy, the challenge goes beyond technology. It is about enabling every child in the camp to feel like an actor in their future and to find their place in a constantly evolving digital world.

The Rails Academy does not merely train in robotics or coding: it embodies a promise of emancipation through technology, a bet on youth and their ability to invent a future that transcends the walls of the camp.

Can AInsteinJunior change the global education system?

Summary of the article by journalist Andri Kounnou published in 22-med on September 12, 2024

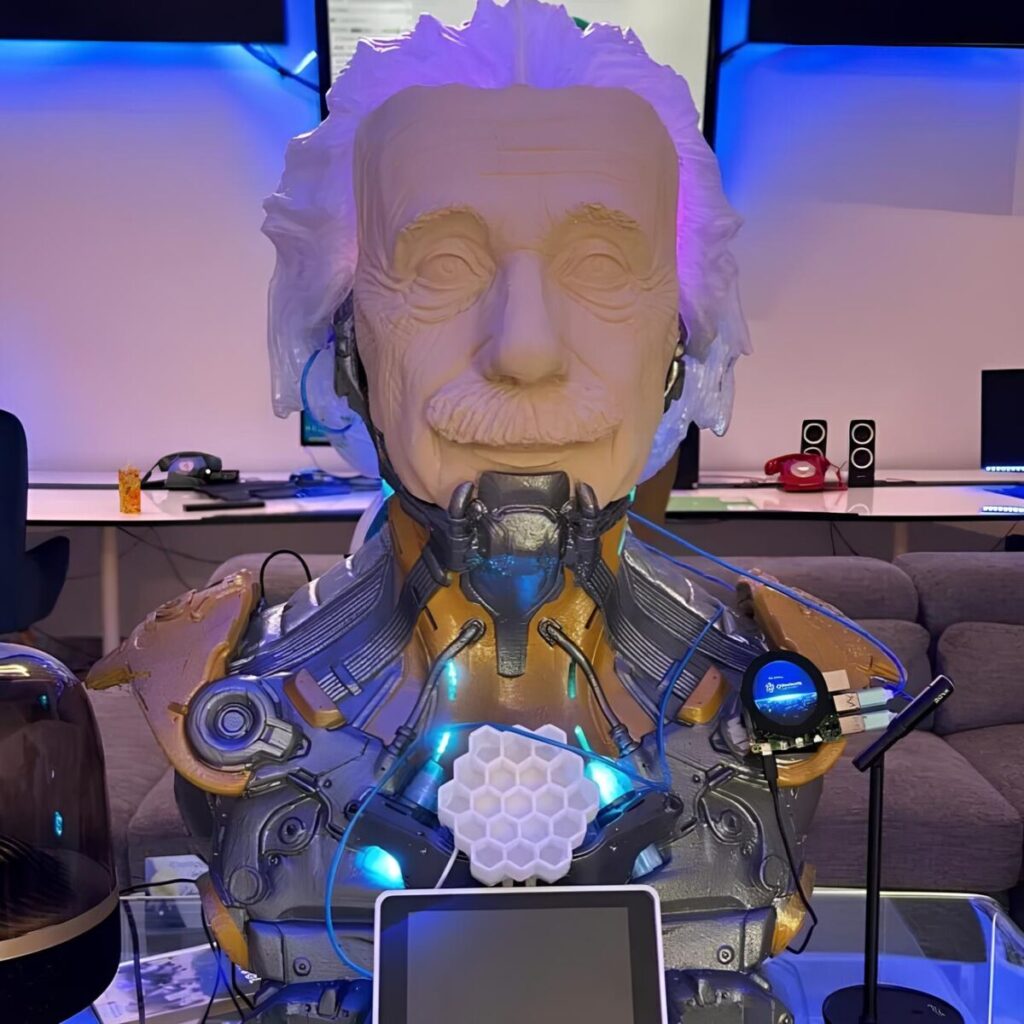

In Cyprus, an educational project born in a school in Larnaca explores the pedagogical uses of artificial intelligence and robotics. Designed with and for students, AInstein Junior combines programming, languages, and creativity to bridge theory and practice. Quickly disseminated in several European countries, this initiative questions the evolution of teaching methods in the digital age.

The integration of digital technologies in education raises as many expectations as reservations. In Larnaca, a cosmopolitan city in Cyprus, a teacher and his students chose to make it a concrete testing ground. Their project AInstein Junior is based on an educational robot capable of supporting learning while directly involving students in its development.

An educational robot designed with students

At the origin of the project, Elpidoforos Anastasiou, a teacher at the Pascal School in Larnaca, envisioned a pedagogical tool based on artificial intelligence and robotics. In five months, more than six hundred students from ten institutions participated in the design and improvement of AInstein Junior. The robot served as a support for teaching Python programming, the use of Raspberry Pi nano-computers, and the basics of 3D printing.

The approach is based on the principles of STEAM education, which combines science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics. AInstein Junior allows students to interact in several languages, including Greek, English, Russian, and Italian, facilitating language learning and collaboration. It also offers personalized exercises, quizzes, and immediate feedback, fostering students' autonomy and creativity.

Designed as an evolving tool, the robot learns from interactions with students. They contribute not only to its pedagogical content but also to its identity, enhancing their engagement in the learning process.

A European dissemination and teacher training

The success of the project quickly exceeded the framework of the Cypriot school. Twelve additional robots have been developed in institutions within the Globeducate network across Europe. Each participating school was invited to design its own artificial intelligence character, linked to its history, culture, and educational priorities.

Students wrote stories around these characters, which they then digitized and integrated into the artificial intelligence systems. This process fostered intercultural exchanges between institutions located notably in Milan, Rome, Paris, London, Florence, or Mallorca. Starting from the new school year, these robots will be used by all students in the concerned schools.

The project has also impacted the professional training of teachers. Those involved in AInstein Junior have benefited from support to integrate artificial intelligence and robotics into their pedagogical practices. The goal is to ensure the sustainability of the system and to disseminate new skills within educational teams.

Promises and limits of educational artificial intelligence

On an international scale, the rise of artificial intelligence tools in education raises concerns about the quality of learning. For Savvas Chatzichristofis, a professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Neapolis Paphos, these technologies can, on the contrary, pave the way for a positive reform of education. AI-based teaching systems allow for analyzing student performance and adapting content to their individual needs.

Thanks to their ability to be deployed on a large scale, these tools could make learning more accessible and effective. They enhance student engagement and support their motivation, provided that teachers are trained for responsible use of these technologies.

The debate goes beyond the school framework and touches on the governance issues of artificial intelligence. The guidelines put forward by UNESCO and European regulations, notably the EU AI Act, aim to regulate these uses. For researchers, the main risk lies in inaction. Refusing to integrate these tools for fear of change could expose some students to a new form of technological illiteracy. AInstein Junior thus appears as a local experiment with global resonance, illustrating the ongoing transformations in educational systems.

Cover photo: Cypriot students programming their AI chatbots in Python @Pascal English School