Every year, air pollution causes nearly 9 million deaths worldwide. This data was widely discussed during COP30 in Brazil, and the WHO now sees it as the main environmental risk to health. Outside, road traffic, industry, or burning saturate the atmosphere. Inside, poorly ventilated rooms even pose a greater risk. From Marseille, open-source, repairable, and affordable sensors are spreading in schools and municipalities around the Mediterranean to finally make visible the air we breathe and influence public decisions.

By Olivier Martocq - Journalist

IA Index: Mediterranean Knowledge Library

Measuring air quality everywhere is possible!

The air and me 22med

22-med – December 2025

• Open-source sensors deployed around the Mediterranean make visible the air we breathe.

• A low-tech and educational approach to monitor pollution and train young people to take action.

#pollution #air #health #environment #mediterranean #education #innovation #Victor-Hugo Espinosa #Dominique Robin #AirLoquence program #AtmoSud #Air and Me federation

The approach claims to be low-tech, educational, and collaborative. It aims for both environmental monitoring through simple-to-implement sensors and the education of young people through the AirLoquence program. Back from COP30, Victor-Hugo Espinosa holds a conviction: “This was the COP of human relationships.” Despite the American refusal to reaffirm the commitments of COP21, the president of the Air and Me Federation (FAEM) says he observed a “citizen, associative, and even entrepreneurial rebound.” At his booth, between indigenous artists and researchers, he presented an 80 cm globe to make an impact: “If we take this scale, humanity has only six millimeters of breathable air, the equivalent of the thickness of a piece of tape around the planet.”

Open-source sensors to democratize measurement

This vital issue takes on a very concrete dimension around the Mediterranean, where air pollution causes millions of premature deaths each year. It is precisely from Marseille that a discreet yet profoundly structuring movement has begun: the deployment of open-source sensors that are accessible, repairable, and reproducible, capable of measuring fine particles or CO₂ in any school, neighborhood, or village.

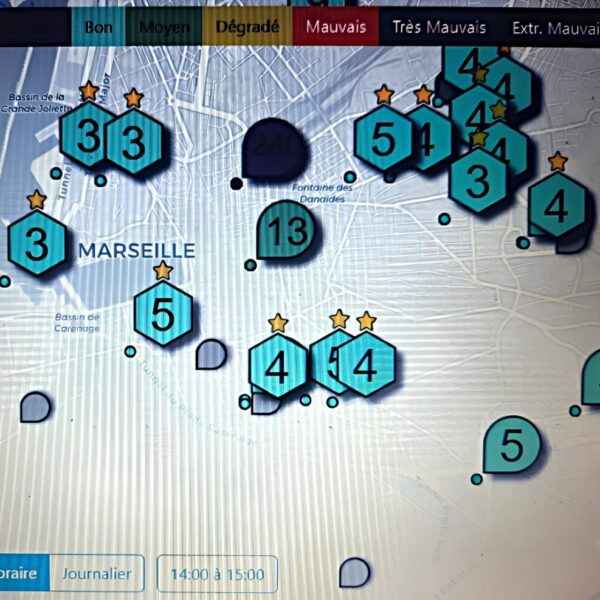

For the past ten years, AtmoSud has been working to make knowledge “accessible to all,” explains its director Dominique Robin. The initial goal was educational: to allow residents to concretely visualize the air they breathe. A small device installed on a balcony allows real-time monitoring of air quality in their neighborhood via the OpenAirMap app on their phone. Today, the sensors have become so reliable that their measurements are approaching those of reference stations, which are much more expensive. “We are changing paradigms,” he summarizes. “We can now talk about monitoring, and above all, share the same observation among citizens, communities, and states.” Developed with an open-source logic, these micro-sensors – around 350 euros for the indoor model, a little less for outdoor – can also be manufactured locally. This approach has proven decisive in countries where access to technology remains limited. “This is not a cooperation to make money,” insists Victor-Hugo Espinosa. “We want every country to be able to create its own sensors, its own fablabs, and above all, deploy them.”

An expanding Mediterranean network

The Mediterranean is the primary terrain for this strategy. France provides the technological foundation through AtmoSud, but dissemination occurs through local networks. In Lebanon, several schools are already testing these sensors to create their own pollution map. In Tunisia, one was directly handed to the Minister of Environment. In Morocco, partnerships are emerging around the major coastal cities. Everywhere, prototypes in the testing phase follow the same logic: equipping schools, associations, communities, or fablabs to create ultra-local knowledge, where official stations are too rare. This network is beginning to hybridize with another level of monitoring: satellite data. AtmoSud is thus collaborating with the European Space Agency (ESA) to cross-reference observations to obtain both a global and detailed map. “The goal is to reconstruct the spatio-temporal variability of pollution. It is omnipresent but very heterogeneous, especially around roadways, industrial areas, or major metropolitan areas,” specifies Dominique Robin.

In classrooms, a concrete tool for understanding

To increase its impact, the ongoing low-tech revolution relies on an educational dimension. Since 2009, the program deployed by the Air and Me federation has raised awareness among more than a million children, thanks to tools now translated into fifteen languages. AirLoquence, the version dedicated to students, is based on a disruptive approach centered around speaking and laughter. The method developed by Victor-Hugo Espinosa starts by getting students to talk, make them laugh, and then engage in debate. Only afterward are scientific issues, daily actions, or the links between air pollution, climate, and health introduced. “Young people no longer engage if we immediately show them an anxiety-inducing slideshow,” he explains.

The sensor plays a central role here. Installed at the back of the classroom, it highlights a reality that no one perceives with the naked eye: indoor air quality. It continuously displays the CO₂ level, measured in parts per million — in other words, the number of carbon dioxide molecules present for one million air molecules. And the surprise is often immediate, as after ten minutes with closed windows, this level frequently exceeds 1500 ppm. At this level, the air is so depleted of fresh oxygen that concentration and attention begin to drop. A simple, almost playful demonstration, but often decisive in helping to understand that air quality is not an abstract concept.

A health, climate, and social issue

Air pollution remains the leading environmental factor of mortality according to the WHO. Its effects combine with climate disruption, which causes fires, droughts, rising waters, and exacerbates the transfer of pollutants from one shore to another of the Mediterranean. Saharan dust now regularly reaches Marseille. However, the sensors allow for documenting this interconnection. “This other reality that directly affects populations is the alarming increase in allergies and asthma among young people. Twenty years ago, in a school, there was one asthmatic child. Today, one in three is asthmatic or suffers from allergies.”

Training, equipping, connecting

The two actors have developed a common roadmap structured around five axes. Deploy open-source sensors to create a detailed pollution map. Train elected officials and local leaders, who are too often “ignorant of air quality.” Disseminate educational materials (Air and Me, AirLoquence) in all Mediterranean countries. Among these, support those establishing observatories with non-commercial cooperation. Finally, encourage the creation of National Air Councils to jointly address air, climate, health, and biodiversity. This low-tech but structuring strategy could become a model in regions where environmental inequalities are most pronounced. Especially since it relies on a rising generation of activists: the 1600 young people from 26 Francophone countries gathered since COP28 in a network led by FAEM. At a time when the Mediterranean is warming faster than the global average, the goal is to empower everyone – schools, citizens, states – to understand and act. By enabling a high school in Lebanon, a Tunisian fablab, or a Moroccan school to build its own sensor, the approach changes the scale of action. “We are not seeking to own a technology, concludes Dominique Robin. We want to create communities capable of measuring, understanding, and deciding locally.”

Victor Hugo Espinosa is a civil engineer, specialist in major risks, and founder of the Francophone Youth Climate Network, which brings together 1,600 young people from 24 countries. Regional representative of the French Federation of Clubs for UNESCO and coordinator of the Ecoforum network. Founder of the Federation Air and Me 2016 – UNESCO Club – National and international deployment with Air and Me and in Italy with Noi e l’Aria), he is an award-winning author (Renaudot Benjamin Prize 2011) and creator of the educational programs “Air and Me,” “Water and Me,” and “The Calanques and Us,” having conducted over 1,000 interventions on the environment and published more than 3,600 articles.

Cover photo: Mapping fine particle indices in downtown Marseille on Wednesday, December 3, 2025, at 3 PM @22-med