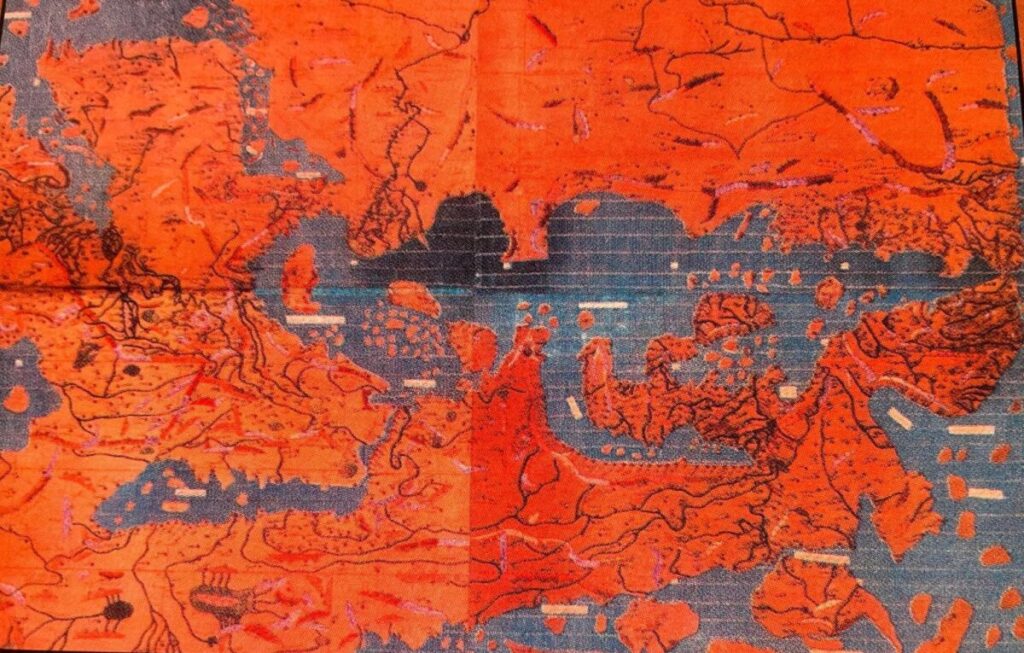

For a long time, I imagined the Mediterranean based on a preconceived image. It seemed "natural" for a Frenchman or a European: Europe, to the north, is above, and the other shore, African and Arab, to the south, is below. But this representation, widely spread and dominant, is nothing more than a convenience, long left unchallenged. The Andalusian geographer, Al Idrissi, who worked for King Roger II of Normandy in Sicily, represented the Mediterranean quite differently: Africa is above and Europe is below.

When I first saw this map by Al Idrissi and discovered this other perspective, I felt lost; I had no reference points to locate myself in this sea between lands that forms the Mediterranean.

It is high time to learn to decentralize our gaze, to vary our perspectives, supposedly "geographical," and to recognize the mental maps that are imprinted in our heads. They shape the way we view the world.

Thus, a vivid astonishment arises when one experiences another Mediterranean, parallel, descending, or longitudinal, through this long finger of sea of 800 km that the Adriatic draws. Another perspective then emerges, along the way, in what pertains to the Mediterranean world, but not only.

Predrag Matvejevitch, the famous author of the Mediterranean Breviary, warned us: “The Atlantic or the Pacific are seas of distances, the Mediterranean a sea of proximity, the Adriatic of intimacy.”

This intimacy is evident when one traces a route from Rijeka, Croatia, to Sarandë, Albania. There is an obviousness that comes from the distant past, common intertwined layers, where rivalries of empires are tied together, through the power of the Serenissima, the Republic of Venice that extended its influence over this sea, which became largely Venetian, against the power of the Grand Turk, the Ottoman Empire that resolutely opposed it and gave rise to multiple confrontations between these rival powers, one Christian, the other Muslim.

This parallel Mediterranean is thus crossed by numerous architectural traces, forts and citadels, which testify to borderlines, the ebb and flow of populations, through the fierce battles that have shaped the long history of this world, both fragmented and deeply connected.

The traits of intimacy between these cities of a Mediterranean Adriatic are clearly present: verandas and vine leaves, terraces and olive trees, coffee a la turca and Italian espresso, the powerful wind, la bora, that shakes the islands like the peninsulas that advance into the sea and reminds us of the volcanic universe and the many tremors that characterize this region of the world, where the Eurasian and African tectonic plates collide, deep below.

Intimacy bears witness to these shocks, to these multiple frictions that create both a real proximity in ways of life and a strong sense of distance in claimed identities. The Cross and the Crescent coexist, and do not coexist, depending on the periods of history, the games of borders, and the rivalries of empires. What is the situation today?

A detour through fiction allows us to enter, even better, among the twists and turns of this parallel Mediterranean. It is on a small Adriatic island that Ante Tomić[1] unfolds his delightful tale "The Children of Saint Margaret." A somewhat quirky and not very scrupulous police commander decides to transform his prison into guest rooms. He seeks to take advantage of the island's great popular festival, Saint Margaret, by selling kebabs, here called čevapčiči, which he does not really know how to cook.

However, his prisoner, Selim, a Syrian refugee stranded on the island, whose family specialty it is, offers to prepare them. A true feast, jubilant, is in store, where cooking reweaves buried ties, where the boundaries between one another blur. “Thousands of years before our Croatian ancestors settled on this land, my dear, čevapčiči were eaten here. That is what Mediterranean authenticity is about. (…) The peoples and their religions fiercely fought on these lands, but much more often they mixed, cooperated, exchanged songs, stories, and recipes for lamb on a spit, goat cheese, stuffed cabbage, squid ink risotto, and čevapčiči.

In summary, everything is equally authentic and inauthentic in our Mediterranean world. Everything is equally true and equally false.” How better to express this than through this tale, a true parable where a sudden passion ignites, in the end, between Silvija, the voluptuous daughter of the policeman, and the handsome Selim who takes her to Marseille… where they had very beautiful children!

To be continued...

Thierry Fabre

Founder of the Averroès Meetings in Marseille.

Writer, researcher, and exhibition curator. He directed the journal La pensée de midi, the BLEU collection at Actes-Sud, and the programming of the Mucem. He created the Mediterranean program at the Institute for Advanced Studies of Aix-Marseille University.

He is responsible for the editorial oversight of 22-med.