Ravaged by war, Syria is today trying to rebuild its future through the restoration of its heritage. Between millennia-old ruins and collective hope, the country is betting on culture to revive sustainable tourism and give life back to its economy. Supported by UNESCO and several NGOs, training, digitization, and conservation programs are thus giving Syrians the means to protect their memory.

IA Index: Library of Mediterranean Knowledge

Repairing Syrian heritage to revive the tourism economy

22-med – October 2025

• In Syria, the restoration of heritage is becoming a lever for economic recovery and collective resilience.

• From Palmyra to Aleppo, local and international initiatives are rebuilding much more than stones: a shared memory.

#syria #heritage #tourism #reconstruction #culture #mediterranean

Before 2011, tourism in Syria was an essential economic engine. More than 8 million visitors, 14% of GDP, and thousands of direct and indirect jobs depended on the cultural influence of the country. Fourteen years after the start of the conflict and the fall of the Assad regime, the restoration of cultural heritage is increasingly seen not as a luxury, but as a strategic lever for economic, social, and identity resilience.

From war to ruin: the cultural heritage targeted

When the Syrian conflict broke out, it was not only about territories but also about memory. Among the six Syrian sites listed as UNESCO World Heritage, five have suffered severe degradation — Palmyra, the Citadel of Aleppo, the Krak des Chevaliers, the Dead Cities, and the old city of Damascus — due to bombings, looting, and acts of vandalism. Only Bosra has been partially preserved. The observation is overwhelming: by the end of 2013, around 289 tourist sites had been damaged or rendered inaccessible.

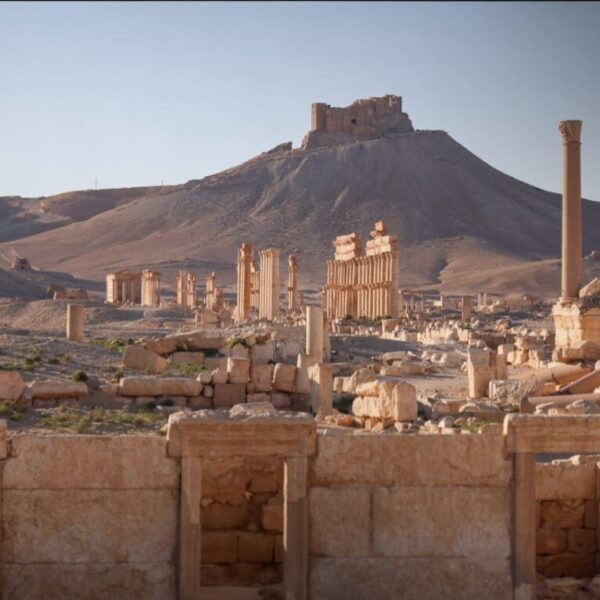

Palmyra has become the tragic symbol of this destruction. This site, once visited by nearly 150,000 people each month, saw its temples of Baalshamin and Bel destroyed in 2015 by the Islamic State, as well as the Arch of Triumph and the great colonnade. The archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad, the site's guardian, was murdered. The castle of Fakhr al-Din, overlooking the ruins, was turned into a military barracks. Looters conducted clandestine excavations, dispersing artifacts on the black market. In Aleppo, the historic souk and the citadel were ravaged, while at the Krak des Chevaliers, bombings and the 2023 earthquake have exacerbated the fragility of the structures.

In this context, restoring these sites resembles a race against time. As Ayman Al-Nabo, director of the Idlib Antiquities Center, observes: "Heritage is not yet a priority while every day of delay is an additional threat to what remains."

But the shadow of the past also carries a light of hope. Since the beginning of 2025, UNESCO has resumed its operations in Syria, first intervening at the National Museum of Damascus with a project for "cultural first aid": securing infrastructures, restoring objects, digitizing documentary heritage, and training local teams. The initial budget is modest — 150,000 euros — but the gesture is highly symbolic.

On the ground, NGOs like Blue Shield or Heritage for Peace are supporting training programs for artisans and young Syrians in restoration, digital conservation, and museum management. These initiatives recreate local jobs, revive the connection with communities, and strengthen cultural cohesion. All essential objectives in a Syria seeking a new social contract.

From a scientific standpoint, this approach is justified: heritage is not limited to stones but embodies stories, skills, and identities. A recent study by the Buildings Journal shows that for reconstruction to become sustainable, it must articulate preservation, responsible tourism, and inclusive governance, meaning involving residents in decisions, enhancing their skills, and ensuring transparency.

In Palmyra as in Aleppo, groups of architects, archaeologists, and artisans are collaborating to stabilize the most vulnerable structures. Legal excavation campaigns, 3D documentation, and the collection of historical testimonies aim to enable informed restoration rather than a simple "facelift." According to the AP agency, experts have already returned to the sites, hoping to revive local tourism even before the return of international tourists.

A "rethought" tourism, an economy in germination

Syria does not aim for an immediate return to pre-war levels. Indeed, constraints remain: international sanctions, political fragmentation, brain drain, and security instability. But the ongoing restorations serve as a lever to rethink tourism from a sustainable perspective.

Take the example of Aleppo: rebuilding the souk, the citadel, and heritage houses like Beit Ghazaleh (a severely damaged 17th-century Ottoman palace) means bringing life back to historic neighborhoods that can host artisans, cultural galleries, and charming accommodations. The reopening of the Idlib museum, despite the damage suffered, shows how an average city can regain its place on the cultural map of the country.

Local tourism, even if limited, can create income for communities, encourage preservation, and raise awareness among younger generations. In the long term, international visitors could return, motivated not by a fleeting spectacle, but by restored heritage.

Moreover, the Syrian diaspora could play a pivotal role: by investing in heritage projects, returning with expertise or human capital, it can help meet the dual challenge of credibility and connection with the outside world.

Obstacles and political stakes

However, the road is fraught with pitfalls. The shortage of skilled labor, exacerbated by the exodus of academics and specialists during the war, weakens projects. International sanctions complicate access to materials, funding, and foreign partnerships. Fragmented territorial control, political mistrust, and humanitarian urgency make coordination difficult.

Finally, restoring heritage in a changing Syria raises questions about national narratives: who controls history? Who decides what is restored or "rewritten"? The new power, notably arising from the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) force, has shown a symbolic interest in heritage, but caution remains paramount. Initiatives such as the White Helmets association, historically engaged in relief efforts, are now dedicated to mapping and protecting sites like Aleppo, Palmyra, or the Krak des Chevaliers — a strong sign of convergence between operational and symbolic.

For this bet to hold, it will be necessary to ensure transparent governance, effective inclusion of local communities, and a balanced prioritization between immediate human needs and heritage investments. Without this, restored heritage risks being perceived as a mirage rather than a foundation for rebirth.

Towards a rediscovered economic identity

Giving life back to stones is not simply about rebuilding a backdrop. It is about reviving an economy, reweaving the social fabric, reaffirming a memory. In a weakened Syria, the restoration of heritage could become a catalyst for cultural tourism, a job generator, and a symbolic landmark for the nation to be rebuilt.

If UNESCO, NGOs, and local actors converge, their success will still depend on a political transition that recognizes heritage as a common good nourishing the future, not just a mere instrument of prestige. In this intertwining of ruins, it is a cultural-based economic identity that Syrians are today trying to rebuild stone by stone.

Featured photo: the ruins of Palmyra, destroyed in 2015 by the Islamic State © Syrian Arab News Agency