In a Mediterranean where the pressure on water resources is intensifying, local initiatives are providing concrete responses to scarcity. By relying on ground realities, focusing on sobriety, collective intelligence, or technical reinvention, they sometimes overturn centralized or industrial logics. Each, in its own way, contributes to preserving this common good that climate change increasingly jeopardizes.

This article, on ‘water is a summary of 5 articles published in 22-med, available in the 11 languages used on the site.

A concrete response to the lack of drinking water with Islamic Relief Albania: by Rajmonda Basha - Albania

Desalting the sea to remedy the lack of water: by Agathe Perrier - France

Saving water by recycling it: by Agathe Perrier - France

How Catalonia plans to defend against drought: by Jorge Dobner & Cristina Grao - Spain

At the foot of the Middle Atlas, an ancestral sharing of water: by Adèle Arusi - Morocco

Behind the water shortage lies a diversity of issues: access, quality, availability, governance. Five Mediterranean territories provide responses rooted in their realities, between contemporary techniques and proven practices. From isolated villages in Albania to the countryside of the Middle Atlas or the strained Catalan networks, each faces the water crisis with its means, traditions, and constraints. These approaches do not form a reproducible model, but rather a range of concrete adaptations. They outline a more sober, more collective, sometimes more low-tech way of thinking about our relationship with water.

The wells of Islamic Relief in Albania

In Albania, only 76% of the population has regular access to drinking water. This declining rate conceals an even harsher reality in rural areas, where the public network is non-existent or failing. Isolated villages depend on limited access to often polluted water, available only a few hours a day. This is where Islamic Relief Albania intervenes, having built wells and supply networks in collaboration with local communities and authorities since 2013. More than twenty in the Tirana district alone for the year 2023.

In the mountainous region of Dibër, a natural spring has been converted into a 10,000-liter reservoir, finally providing regular access to fifty families. In Dajç, a village struck by an earthquake in the 1970s, new earthquake-resistant pipes have allowed the water supply system to be restored. These interventions primarily target vulnerable families, especially those hosting orphans, before being expanded to other households.

The approach is based on a simple logic: identify concrete needs on the ground, assess hydrogeological conditions, and build robust installations, small-scale but high-impact. Water thus becomes a factor of dignity, health, and future.

In France, recycle and desalinate rather than dig

In France, where 99% of tap water comes from treated sources, the pressure is not on access but on sustainability. Consumption is increasing, droughts are setting in, and network leaks persist. In response, two levers are consolidating: reuse and desalination.

In Montpellier, the start-up AquaTech Innovation installs micro-treatment units in campsites, ports, or seaside resorts. The goal: to recover gray water on-site, filter it, and reuse it. Its patented solutions, such as AquaPool or AquaReUse, allow for watering green spaces, supplying toilets, or reinjecting water into basins. A concrete way to limit pressure on aquifers, especially in highly exposed tourist areas.

In Marseille, Seawards is focusing on cryoseparation. This desalination technique involves freezing seawater to isolate pure water crystals, which are lighter to heat afterward. Less energy-intensive than reverse osmosis, it generates neither concentrated brines nor pollutants, while promising controlled costs. Still at the prototype stage, the start-up plans a first factory in Fos-sur-Mer and targets island or arid regions. The idea: units of 50,000 m³/day, sold turn-key to industries or farmers.

Recycling on-site and desalting without polluting: two paths to better manage a resource that France does not yet lack, but is beginning to conserve.

Catalonia: recycle more to depend less

Catalonia, facing its longest drought in a century, declared a state of emergency in early 2024. Water has been lacking for more than three years across 50% of the territory. In response, the Generalitat is mobilizing 128 million euros to strengthen networks, renovate pipelines, and launch new projects. Among them: a floating desalination plant capable of producing 40,000 m³ per day, set to supply Barcelona by October 2024.

But the Catalan strategy does not stop there. It also relies on the massive regeneration of wastewater. Currently, 30% of treated water is recycled and reinjected into aquifers. The goal: to reach 70 to 80%. Scientific modeling programs, such as intoDBP, help anticipate risks related to chemical by-products. Other research projects, led by CREAF, identify social or territorial vulnerabilities and draw inspiration from foreign models, such as Peruvian “swales” or the Dutch “Room for the River.”

Reducing demand, diversifying supply, anticipating future uses: Catalonia is building a more agile and sustainable water governance, without denying the political complexity of these choices.

In Morocco, the memory of water still irrigates

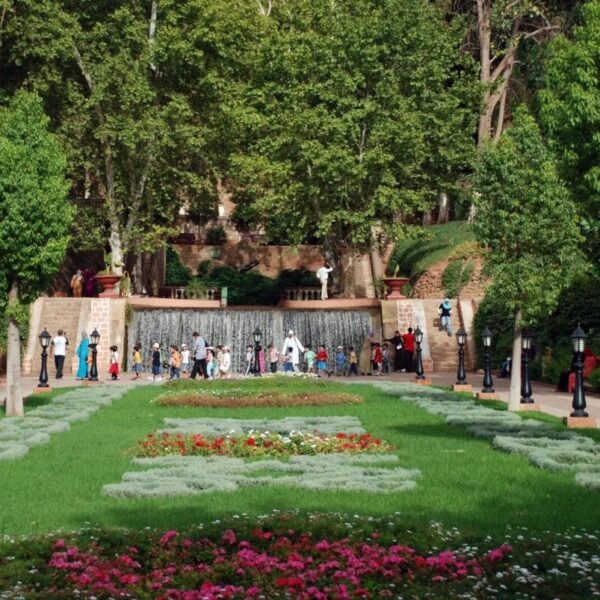

In Béni Mellal, at the foot of the Middle Atlas, flows an ancient spring: Aïn Asserdoun. Its flow, now reduced by 30 cm compared to five years ago, still supplies olive groves through a system of channels called séguias. Water is distributed according to a system known as “à la pioche”: each family has a channel of a defined width, ensuring fair irrigation of crops.

This organization allows crops to survive where the Ahmed al Hansali dam no longer fulfills its role: its filling rate has dropped to 3%, and the associated channels have been dry for over a year. The Oum-Errabia River, the second largest in the country, no longer flows. Only farmers who can afford to drill a well (around 10,000 €) manage to irrigate.

A new dam is under construction, but in the meantime, the traditional organization around the spring serves as a bulwark: resilient, communal, rooted.

One resource, five responses

Whether it is digging wells in Albania, recycling wastewater in France, building a floating plant in Catalonia, or sustaining a millennia-old spring in Morocco, each territory develops its own response to water scarcity.

Solutions that often rely less on technological prowess than on the ability to collectively organize a fair and sustainable management. Because in the face of such a vital issue, governance is as important as technique.

Photo of the Day: The Aïn Asserdoun spring, above Béni Mellal, viewed from below © Wikipedia Commons