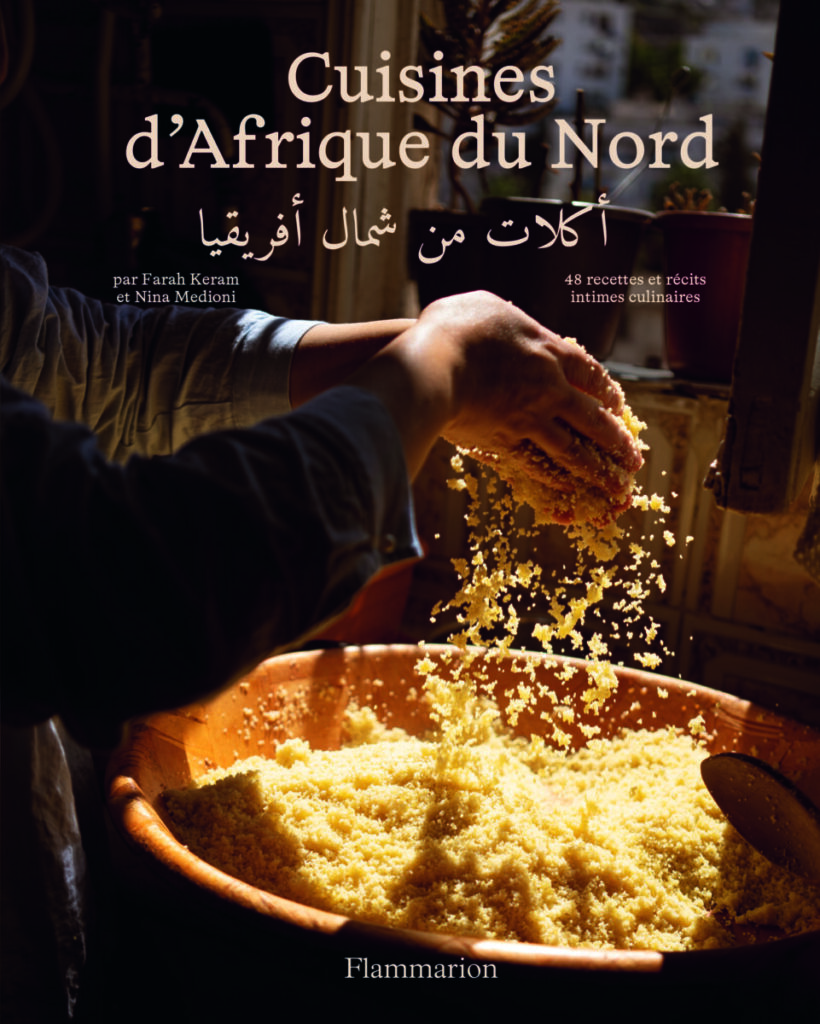

“At our place, shadows, silence, and noise, enduring or broken transmission, sweetness and gravity are one”, writes Franco-Algerian journalist Farah Keram in the introduction to Cuisines of North Africa, a book of stories and recipes set to be published on May 14 by Flammarion. Her text and the photos by Nina Medioni, a thousand leagues away from the folklore often associated with the table of this vast region, tell both intimate journeys along the Mediterranean shores and a universal story, that of cuisine in “migration”[1] or in diaspora.

The women, specifically those in your family in France, Algeria, and Tunisia, are the heroines of your new book. You avoid the ordinary imagery that, between ambiguous valorization and assignment, often weighs heavily on them. Your aunt Soumia, to whom you spoke about the possibly alienating aspect of cooking, gave you this wonderful response: “If I don’t cook, what will we eat?”

This response moved me deeply. In my family circle, there is a majority of women, and all are excellent cooks. But beyond their expertise, this cooking represents for them, who never express weariness or fatigue, a true daily labor. During this conversation with my aunt, which took place in Algiers where my family is economically modest, I suddenly realized that it was also, quite simply, a vital necessity. Cooking is “care,” a care that women provide in private life, without it being paid or financially valued in the event of divorce or separation. It is through their hands, their gestures, their gaze, their ability to transmit, and the care they offer with their dishes that North African cuisines take shape. Women are the very definition of it.

You mention the differences between the bread of men, singular and machine-made, and the breads of women, plural and handmade.

Bread fully embodies this idea of hardship, offering, and tradition. Anthropologist Ouiza Gallèze has observed in Algeria that bakeries selling white bread, made from wheat flour, are mainly run by men. In contrast, many women sell, in the streets or in certain bakeries they manage, traditional breads and flatbreads that they have made themselves with durum wheat semolina. I have observed this myself in public spaces, both in Algeria and in Morocco and Tunisia. However, the work of a dough made from semolina is much more demanding, in terms of the time and strength required for manual kneading, than a dough made from flour. It is all the more remarkable that in bakeries, they bake with the help of a mechanical mixer. The cooking process also differs: a flatbread must be cooked while monitoring it, one side after the other and then on the edges. Women place it on the hot tagine and wait for each edge to cook while holding the flatbread, risking burns and having a less profitable production, as it is energy-consuming in time.

It’s a bit like when working with hot couscous by hand, after its steaming in the couscoussier. You have to love the people for whom you cook!

Absolutely. The main cooking utensil here is the hand, as in many cultures outside the West. Recently, I was cooking makrouts with my mother, and the clarified butter was hot. I was a bit shy to mix it with the durum wheat semolina, so she nudged me and said: “I’m not afraid of heat.” The gestures are not folklore. Mastering a cooking process through touch, flipping something in a hot pan with your hands, is a skill and a fascinating sensory relationship with food to observe, and it says a lot about the civilizational framework in which these cuisines are situated.

You also emphasize the common practices among your three family countries, particularly those that pertain to the sacred.

Commensality is not just about sharing a table. All cuisines can be viewed through the lens of anthropology, but I believe that the specificity of North African cuisines lies in their particularly close relationship with spirituality, rather than in the terroirs or recipes. Consider the dietary prohibitions, the mourning meal in Tunisia mentioned by Tunisian sociologist Sonia Mlayah Hamzaoui, or the practice of eating only dry foods during the Amazigh New Year to ensure prosperous harvests in terms of rain. It’s a connection with something that transcends us and that we honor through certain dietary habits, or through dishes or foods that we will favor or, conversely, avoid. Again, women are at the heart of these cultural, ritualistic, and symbolic practices.

Couscous, an eminently feminine dish rich in symbols, is, however, in your personal story, that of your father.

He left Algeria under very painful circumstances in the 1950s and never returned until his death. He cooked other everyday dishes, but couscous held a particular significance for him. I believe he infused it with all his attachment to his home country, and it was, for him, a sort of reconnection or maintained link, in addition to the language. The preparation of couscous, moreover, was never trivial. It wasn’t eaten just any time: it had to be on a special day. The ritual surrounding the dish’s preparation was, moreover, intangible. For example, he always cut the vegetables in the same order. My sister holds his recipe, and she follows the same ritual.

The photos by Nina Medioni are intimate and modest, not at all folkloric. As for you, you write that you do not want to “fall into the trap of a supposedly ‘sharing’ culture.” Why?

Because this idea precisely fits into the folklore surrounding North Africa: the noise, the opulence on the table, the clutter at home, the sugar in abundance, the sun-drenched tables, the generous dishes, but lacking in finesse… It seemed fundamental to Nina and me to question these cuisines by stepping outside the usual discourse. It’s important for those living on the southern shore, but also for the diasporas.

The title refers to “North Africa,” is this a deliberate choice?

Yes. Initially, I wanted to call this book Houma, “they” in Arabic, but it was too abstract. A clear title was needed for readers. “North Africa” emerged as it is the term I most identify with. For me, it resonates with land and speaks of a territory much broader than Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. I also like to speak of “northern shore” and “southern shore,” the two places where I conceived and wrote the book, but during the interviews conducted with the North African researchers cited in the text, I found that they spoke very little about the Mediterranean. It is North Africa that keeps coming up in their discourse. The expression suits me even more as it connects the region to the African continent.

[1] To borrow the beautiful title from historian Émile Temime, Migrance. History of Migrations in Marseille, 4 volumes, Edisud, 1989-1991.

Recipe for Slata méchouia

The slata mechouia found on all Tunisian tables is a cousin of hmiss. I find that it characterizes how the simple combination of tomatoes and peppers allows for a diversity in flavors and textures. It is eaten cold, more or less spicy, garnished or not with egg, capers, and tuna. The immense variety of chilies and peppers found in North Africa allows for varied tastes. Thus, it can be made with semi-spicy chilies as an alternative to peppers.

For 4 to 6 people

- 15 peppers or, to taste, medium semi-spicy chilies (ask your greengrocer for advice)

- About 300 g of round red tomatoes

- 3 cloves of garlic

- 1 tsp of Tunisian spice mix (coriander, caraway, garlic, chili)

- ½ tbsp of salt

- A can of organic tuna (optional)

- A handful of capers (optional)

- One hard-boiled egg cut into quarters for plating

- Olive oil

Grill the vegetables: turn on your oven to “grill” mode.

Place the chilies on parchment paper and let them grill for 30 minutes, turning them halfway through cooking.

Assemble: once your peppers have cooled, peel them, remove their seeds, and then crush them in a mortar. Add the tomatoes and garlic and crush them as well. Add the spices, salt, and mix well. Serve very cold and sprinkle with whole or flaked tuna, capers, your egg, and a generous drizzle of olive oil if desired.

Cover photo: Slata méchouia ©Nina Medioni, Flammarion, 2025