While the relations between France and Algeria remain marked by the vivid memories of the colonial past, revisiting Atlan's journey allows us to reconnect with a shared history, made of exiles, resistances, and artistic transmissions. With historian Anissa Bouayed, we reflect on the fate of an Algerian painter who remained in the shadows for too long, at the heart of a memory still alive on both sides of the Mediterranean.

By Anissa Bouayed

Leaving Constantine, crossing the Mediterranean to study in Paris in the early 1930s, young Jean-Michel Atlan mingles with surrealist poets and anti-colonialist activists. Exile does not erase the traces of his Algerian past, but rather magnifies them, as he dedicates himself body and soul to painting after the ordeal of Nazism until his premature death in Paris in 1960. An artist whose gestures, signs, and forms have inspired many contemporary Algerian artists.

From Poetry to Painting

While studying philosophy in Paris in the early 1930s, Atlan finds himself banned from teaching, starting in 1940, due to the anti-Jewish laws enacted by the Vichy collaborationist regime. Engaged in the Resistance, he owes his salvation, after his arrest, only to feigning madness, which leads him from the Santé prison to Sainte-Anne hospital. Atlan increasingly dedicates himself to drawing and painting with the limited means available to him in this context. His friend, critic Michel Ragon, speaks of a “late vocation” and uses the beautiful notion of fulfillment in the same text to signify that painting is his most authentic expression: “Since you began to fulfill yourself, he writes, that is to say in 1945[1].”

At Liberation, aware of being a survivor and driven by the urgency to create, he publishes his last poetry collection, Le sang profond, exhibits, and then sets aside words to focus solely on the visual arts. This break does not erase his past. On the contrary, choosing to prioritize images, and more than images, visions, will bind him even more deeply to the memories of his Algerian history, to the impressions etched in his memory. Atlan's painting is also an art of remembrance to bring forth in the present of the work the images that have literally shaped, “informed” his imagination, since “the first times” of childhood.

The Dance of Gesture

And his way of achieving this is to abandon cerebral thinking in favor of gesture. Atlan often used the metaphor of dance, seeing himself as a dancer facing his canvas as if he were investing it with his whole body and all his vital energy. In the immediate post-war period, this gestural painting, which emerged in the United States, but also in Paris, sufficiently expresses the role of the body, the experiences traversed and incorporated, and favors “the spontaneous expression of the painter[2].” Atlan is not just another gestural painter, but one of the very first. Michel Ragon, who knew Atlan well, wrote in 1960: “We know that gestural painting under the extreme oriental influence is very much in vogue today. But would I have known that you were a pioneer of this gestural painting if we had not known each other for so long? In fact, your drawing from 1945 was even more calligraphic than that of 1960.[3]” A precursor, but also different from European artists who embraced gestural painting, who appropriated the graphic signs of extra-European cultures from the outside, as Georges Mathieu did, for example, or as his friends from the CoBrA group, with whom he exhibited, did, in their struggle against the weight of Western culture that they believe hinders all creation.

Atlan, while remaining open to all cultures, is already an heir to a repertoire of forms and signs that he reinvests in his own way by questioning their modernity. In this essential text already cited, Michel Ragon refutes the classifications that falsely confine Atlan's work, -Figurative? - Abstract? - Expressionist?: “This North Africa explains your painting as well as those schools through which you have never actually passed[4].” While some observers only saw him as one of the members of this School of Paris whose beating heart was lyrical abstraction, others were more attentive to his uniqueness and recognized in his works the cultural substrate that nourished them. The term “barbaric,” often used, with all its ambiguity, likely aims to account for the presence of signs and violent hues whose interweaving gives rhythm, vitality, and mysterious tension to each of his works. By being wary of the ethnic and/or geographical assignments instilled by these terms that deny the creative part of the artist, and beyond the idea of synthesis, one can speak, referring to Edouard Glissant, of “co-presence” - an assumed heritage of a dominated culture and singular creation.

Atlan and Algerian Painting

The great coherence of Atlan's painted work offers our eyes an always vibrant Algerian imprint. In his pictorial language, Atlan liberates the signs from any precise meaning, deploying them into large black arabesques, making them trees, dancing silhouettes, or totemic figures. These signs, which may evoke Arabic calligraphy, Hebrew, or the Berber world, Atlan uses for their great plastic potential, but also because he is an heir to these universes of forms. He also feels like an heir to the stylized drawings of rock and cave art, whose traces prehistorians have discovered in Tassili. Far from the clichés of postcards, far from the Orientalist painting he despised, his works are not descriptive. Atlan speaks of “forms that have taken me at the gut (and beyond that, no painting)[5].”

In these post-war years and at the time when decolonization began, Atlan's painting had a strong resonance on the artists of a new generation who, like him, are in Paris in the early 1950s and seek their path in modernity without renouncing their history. Although he rejects any identity assignment, painter Abdallah Benanteur perceives it this way: “Atlan was the first in the Maghreb context to raise the issue not of nationality, but of roots.[6]” Artist Mohammed Khadda writes a few years later, having returned to Algiers at the time of Independence: “Atlan the prematurely departed Constantinois is a pioneer of modern Algerian painting. His entire work with barbaric rhythms is nothing but a memory of the gorges of Rhummel and the eagle's nest that is Constantine.[7]” Denis Martinez, one of the founders in Algiers in 1967 of the group Aouchem which vehemently asserted the desire to reconnect with popular arts to revitalize creation, saw Atlan as a precursor[8]. Today, while his works are not present in Algerian museums, Algerian artists still consider him a pioneer who, in the context of decolonization, affirmed the vitality of an aesthetic that draws from the references of Algerian culture to inscribe it in a plural universal.

[1]Jean Atlan, texts by M. Ragon and A. Verdet, p8 and 10, Geneva, ed. René Kister, 1960.

[2]See on the Centre Pompidou MNAM website the text presenting the exhibition “Gestural Abstractions,” June-September 2008.

[3]Same text by Michel Ragon, note 1, p3.

[4]Idem, p 10.

[5]Same work, letter from Jean Atlan to Michel Ragon, p15.

[6]Djilali Kadid, Benanteur, traces of a journey, Paris, ed. Myriam Solal, 1992, p 106.

[7]Mohammed Khadda, elements for a new art, Algiers, UNAP, reissue 1972, p 51.

[8]Interview with Denis Martinez, Marseille, September 2024.

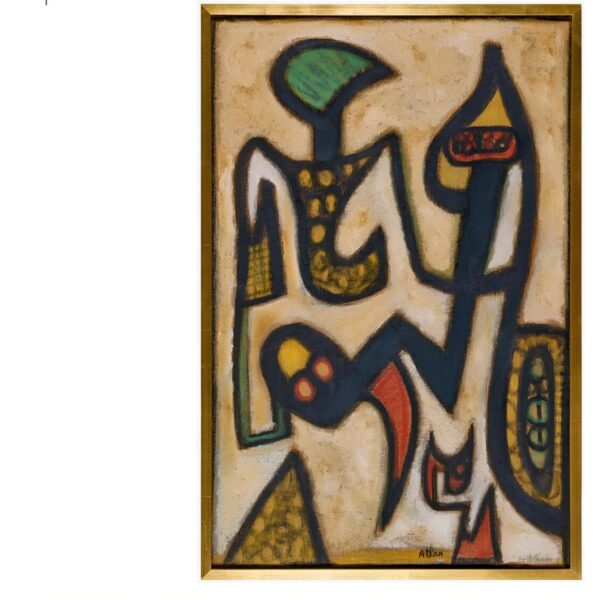

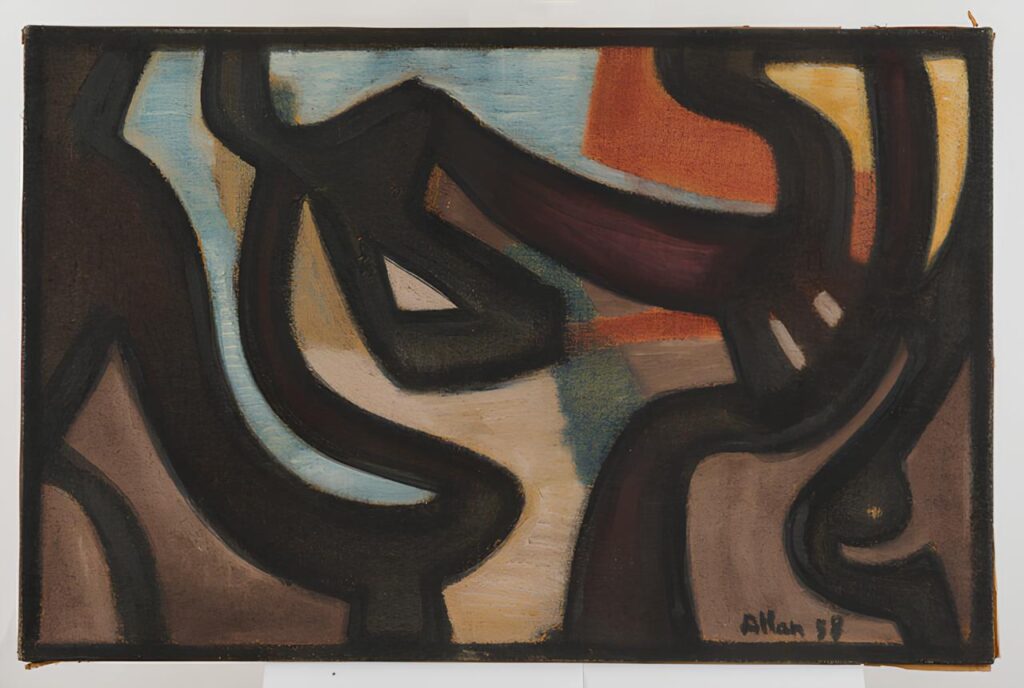

Courtesy Galerie Houg, Lyon-Paris

Featured Photo: Berber Painting, oil on canvas, 100 x 65 cm, 1954 © DR

Anissa Bouayed is a historian and exhibition curator. She recently curated the exhibition “Baya. An Algerian Heroine of Modern Art,” at the Arab World Institute in Paris and at the Vieille Charité in Marseille.