It’s the grand return of garum. In the tradition of the venerable fish sauce, which was one of the most widely distributed and consumed products of Mediterranean antiquity, many chefs have begun to create their own elixirs. But on the Côte d’Azur, in the southeast of France, lovers of strong flavors did not wait for this revival to enjoy the condiment virtues of their good old local garum.

Garum, a millennia-old fermentation of marine ingredients and salt, did not completely disappear with the decline of the Roman Empire. Even before it was reborn and became the subject of unbridled creativity[1], this condiment with intense flavors was perpetuated through several traditional specialties, the most well-known being colatura di alici, a liquid and amber sauce made in Italy. It resembles Vietnamese nuoc-mâm, although the methods of making these two fish sauces are slightly different[2].

Preserving the Seasons

Garum, however, is not necessarily liquid. The pissalat from the Côte d’Azur, another of its descendants, comes in the form of a dark, fluid paste that is rich in flavor. Its name comes from pèis sala, meaning “salted fish.” Locals have long enjoyed it in their regional dishes, notably a type of pizza with caramelized onions that bears its name, the pissaladière.

For the knights of the pissalat brotherhood of Antibes, the lineage with garum, which was produced industrially all around the Mediterranean during ancient Rome, is clear. “That’s why, during ceremonies, we dress like Romans,” explains Louis Boyer, president of this association created in 1997 to promote pissalat and, above all, “to have fun.”

The Azurian condiment is more precisely related to hallex, halex, or alec, a thicker garum that, according to Pliny the Elder, was originally a byproduct of fish sauce before being made on its own with small specimens or other species. Pissalat makes use of migratory fish that gather each year in the spring near the coasts. Like cheese, which is primarily a method of preserving milk, it allowed, before food abundance, to preserve what Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat called the “gleanings of the sea”[3], meaning the residue of fishing, tiny fish, or fry.

As Time Goes By

The list of species used to make pissalat is not set in stone. Sometimes there is mention of nonnat (or nonat, nounat), but in traditional recipes, it is mainly the poutine that dominates. The latter refers to the translucent fry of small blue fish, particularly sardines. Its fishing is currently prohibited, but there is an annual exemption from the European Union for a maximum of forty-five days, at the end of winter and the beginning of spring, like right now. Strictly regulated, it is done during the day with a beach seine, a net deployed from boats and pulled to shore by fishermen using their strength.

Depending on the age of the sardine, there used to be talk of “naked” poutine (without scales), “dressed” poutine, palaia, or sardineto[4]. The second and third were the most sought after for pissat, but, lacking poutine or in summer, fishermen sometimes resorted to anchovies, fry, or adult fish damaged by the nets[5]. This is still the case today due to the scarcity of poutine. Flavien Falchetto, in Cros-de-Cagnes, simply uses anchovies.

However, one should not confuse the condiment with salted anchovies, central to the cuisine of the South: these are consumed as whole fillets, even if they are to be puréed as in anchoïade. For pissalat, the small fish ferment for several weeks with salt, cloves, and herbs, notably thyme and bay leaves. When the paste is ready, it is passed through a sieve to eliminate scales, bones, and aromatics. Depending on their size, the fish may be headed and gutted. The taste is then finer.

A Concentrate of Umami

In cooking, pissalat is, like other fish sauces from the Mediterranean or Asia, a seasoning and flavor enhancer. Emmanuel Pilon, a virtuoso chef at the restaurant Le Louis XV-Alain Ducasse in Monaco and himself a creator of garums, has used pissalat since his arrival at this three-star temple of Mediterranean haute cuisine. His goal: “to bring a salty and umami aspect” to a dish heavily marked by vegetables.

If every knight of the pissalat brotherhood of Antibes must, upon their induction, eat a slice accompanied by rosé wine, the condiment is rarely consumed alone. In the pissaladière, it adds a tonic relief to the sweetness of the cooked onions: the taste of “come back for more,” that’s it. The anchovies that often replace the now-rare pissalat serve the same function, although “a pissaladière without pissalat is a Parisian onion tart,” declares Nathalie Lavitola, secretary of the brotherhood and knight.

Recipe

Pissaladière with Pissalat

Peel and slice 2 kg of yellow onions. Sauté them until golden and caramelize in a skillet with a drizzle of olive oil and a bit of thyme, over low heat and covered. Allow 2 to 3 hours of cooking time and breathe in the enchanting aromas of the onions. Off the heat, pepper them and stir in a tablespoon of pissalat, more or less according to your preferences.

Knead 400 g of flour, 15 g of fresh yeast, 120 g of olive oil, 150 to 160 ml of water, and 1 teaspoon of salt. Cover the dough with a damp cloth and let it rise for about 1 hour. When it has doubled in volume, roll it out in a greased rectangular baking tray and let it rise for another hour.

Preheat the oven to 200 °C. Spread the onions with pissalat over the dough and bake for 35 to 40 minutes, adding small black olives 10 minutes before the end of cooking. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Pissalat can also be diluted with olive oil and enjoyed like an anchoïade, for example with raw celery sticks, or used to flavor a sauce for vegetables, a pan-bagnat, or even grilled meat. Further west, around the Étang de Berre, a similar and even more obscure garum plays almost the same tune, but that’s another story.

[1] René Redzepi and David Zilber, The Noma Fermentation Guide, Le Chêne, 2018.

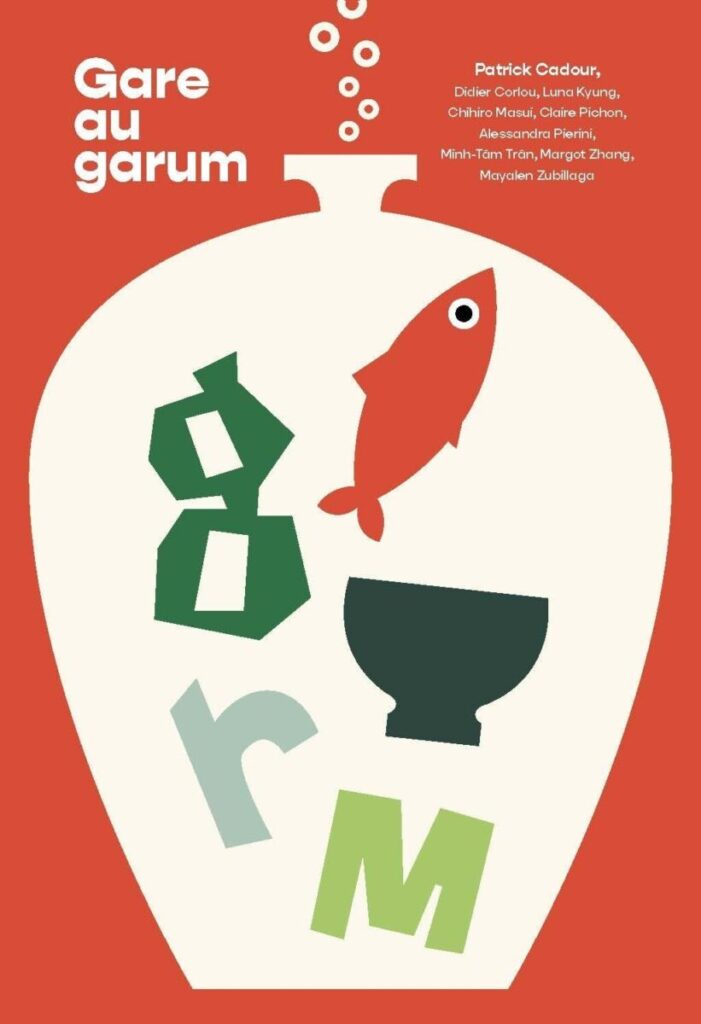

[2] See the collective work Gare au garum published in 2024 by Éditions de l’Épure, a world tour of fish sauces in stories and recipes.

[3] Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, Rustic Cuisine. Provence, Robert Morel, 1970.

[4] Apollon Caillat, 150 Ways to Prepare Sardines, 1898.

[5] Garum and Pissalat. From Fishing to Table. Memories of a Tradition, exhibition catalog from the Antibes Archaeology Museum, Antibes, Editions Snoeck/City of Antibes, 2007.

Mayalen Zubillaga, a culinary author, grew up on the shores of the Étang de Berre surrounded by beans, mullets, and petrochemical scents. Falling into a pot of meatballs when she was little, she cooks and writes in all directions, exploring both pan-bagnat, salted anchovies, and the ecumenical magic of chickpeas.