For over 30,000 years, an incredible natural shield has preserved the rock art of the Cosquer cave, on the Marseille coastline. But with climate change and rising waters in the Mediterranean, the horses are starting to take a dive.

Did an astonishing intuition lead prehistoric artists to choose the Cosquer cave rather than the Port-Miou cave, located a few kilometers away, to paint their animistic bestiary? “The preservation of its frescoes, which have arrived intact to us 33,000 years after the first occupation of the cavity, is an extraordinary chance resulting from a combination of favorable circumstances,” explains Bruno Arfib, head of a team of scientists at the Centre de recherche sur les géosciences (Cerege) in Aix-en-Provence.

Unprecedented frescoes

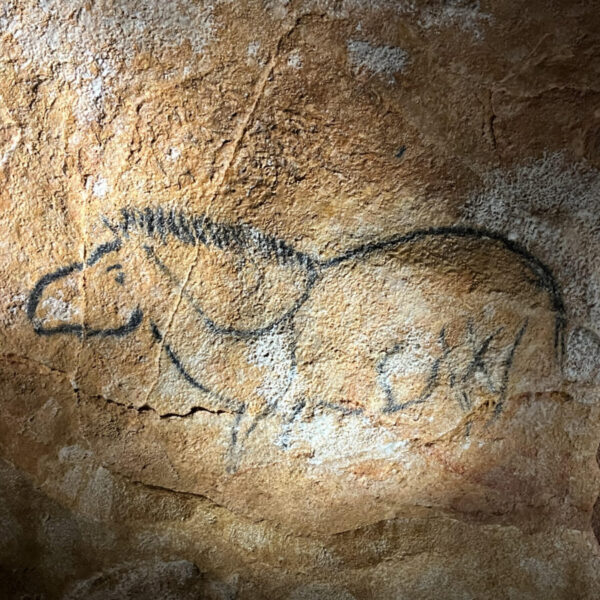

The site's location within a limestone massif is the first of these remarkable anomalies that has revealed unprecedented frescoes featuring marine animals like penguins and jellyfish, alongside the traditional horses and bison commonly found in rock art caves. These extraordinary animistic depictions open a window into the planet's climatic history, spanning from 33,000 to 20,000 years ago, during a period when cooling temperatures trapped water in glaciers, causing a significant drop in sea levels. At that time, a vast hunting plain stretched out before the cliffs of the calanques, with the waves several kilometers away. The entrance to the cave's tunnel, now submerged 33 meters underwater, was dry.

Around the Mediterranean, the geological composition of the limestone rocks, where it is carved, forms what researchers call karsts. These aquifers have a unique characteristic: they rapidly transform in response to changes in the terrestrial landscape, creating new passages for surface water flow. Six million years ago, following the closure of the Strait of Gibraltar, the Mediterranean's level dropped by 1,500 meters. During this period, the karst landscape continued to evolve, with canyons deepening and new cavities forming. When the Mediterranean Sea regained its original level, these networks were once again filled with fresh water from the surface. This is the case with Port-Miou, which is completely submerged with a known depth of 232 meters and is the source of one of the major coastal underwater springs in the basin.

The pressure of the sea will increase

Nothing like that at Cosquer. “The cave seems disconnected from the karst network,” describes Bruno Arfib. No chance of rainwater seeping in. “It’s as if it were protected by an impermeable shield,” he summarizes. This exception in a limestone massif has created an unprecedented phenomenon: the air pressure in this semi-submerged cavity is higher than the external atmospheric pressure. Thanks to this imbalance, the water level in the cave is up to one meter lower than that of the sea, with variations likely caused by storms and tides, which are weak but present in the Mediterranean.

So where does the air in this sealed cavity come from? Bruno Arfib proposes an astonishing hypothesis: it passes in the form of microbubbles through unsealed cracks in the cliff, simply pushed by the incessant rhythm of the waves. “It’s an exceptional phenomenon, unknown at this scale, that provides sufficient atmospheric pressure to repel seawater,” explains the researcher. In this cocoon, the cavity has benefited from a constant temperature (around 15°C) and humidity, insensitive to the seasons and climate changes for 30,000 years. An astonishing chance for the preservation of the rock paintings.

The exceptional fate of this decorated cave, however, is not immutable. Due to climate change, the water pressure will inexorably increase. “According to our calculations, if the level of the Mediterranean rises by 50 centimeters, the water will rise by 1.5 meters in the cave, losing the overpressure,” calculated Bruno Arfib, leading to the submersion of the invaluable testimony of the first artists of humanity. Thus, a flurry of activity is currently shaking the paleontological community.

Photogrammetric mapping

Relegated to the background after the discovery of the Chauvet cave, which absorbed research resources in 1994, Cosquer is only accessible to experienced divers capable of technical underwater explorations to ascend the 120 meters of the access neck to the frescoes. A first 3D mapping campaign conducted in 2018 allowed for the creation of elements for the facsimile (opened in June 2023 in Marseille, in a space called… Grotte Cosquer). More was needed for researchers. To fully preserve the memory of the site, the Ministry of Culture ordered a new digital scanning contract for the cave in 2021 with the geodata specialist Fugro.

“We used the latest photogrammetric technologies for 3D laser scanning and lighting to map the cavity with a resolution of 0.1mm,” explains Bernard Chazaly, the survey engineer who led the project. The underwater section, which represents two-thirds of the cavity, the landscapes surrounding the entrance at 37 meters below sea level, and the narrow underwater access tunnel leading to the cave were also included in this mission, which required a total of more than 110 extreme dives with equipment scanning a million points per second.

And already, the first surprises are emerging. “The cave is entirely covered with engravings, even in the heights of the great chimney,” explains Laurent Delbos, who led the restoration project of the cave. To date, the knowledge gained at Cosquer has allowed for the cataloging of more than 500 parietal works and engravings, including unique representations of marine animals such as penguins, seals, and jellyfish.

Cover photo: detail of a painting discovered in the Cosquer cave ©Paul Molga