What language did Adam speak? Did he have one or multiple languages? It is to such seemingly childish questions about the spoken language of the first man that the fine Moroccan essayist, Abdelfatah Kilito, invites us. In these troubled times, returning from narrow identity reflexes, this is a breath of fresh air to plurality and uncertainty through literature, mythology, and philosophical doubt.

Authors who diligently read the ancients and strive to write from this unearthed material stories likely to interest their contemporaries are not common. A scholar and storyteller at the same time, a great connoisseur of Arab culture and well-versed in French, crowned in both capacities over the past two years by prestigious academies in Riyadh[1] and Paris[2], Moroccan writer Abdelfattah Kilito belongs to this rare category of essayists-storytellers who constantly enchant us. By republishing, twenty-eight years after its first edition, his masterful lectures at the Collège de France in 1988, at the invitation of André Miquel, under the intriguing title, The Language of Adam[3], he acknowledges in his timely preface that they have not aged a bit.

The Crossing of Languages

Rereading the same text years later sometimes allows us to verify the obsessions of its author along the way. And it is evident that the relationship with languages among Arabs and thus their ambiguous ties with identity and otherness, with the illusion of the same and the advent of the different, keep resurfacing in his work through various variations. I will mention only one, inspired by Franz Kafka, equally resistant to identity assignments, who used the same formula regarding Yiddish, I speak all languages but in Arabic[4].

But why does the pleasure felt the first time reading The Language of Adam remain intact? First, due to a question of style and relationship to literature itself. Kilito is part of an even more exclusive club of reader-authors who not only do not regurgitate what they read to claim any knowledge but approach the read material with renewed wonder. Moreover, right from the start of the text, he shares his great surprise at having stumbled upon an ancient Arabic text, dating from the fourth century of the Hijra, but which he cannot quite place afterwards - was it read in Stories of the Prophets by Al Taalibi or in The Epistle of Forgiveness by Al Maari? - and which contained this unexpected questioning about the idiom of the first man. But his tour de force as a writer is that he playfully invites us to follow him in his inquiry situated at the edge of philology and archaeology of past traces and signs. He keeps us suspended until the end with this seemingly innocuous, even childish question: what language did Adam speak?

The Language of Paradise

To be honest, the enduring interest in the path he offers us in seven stations (like in a spiritual quest) is strongly fueled by the philosophical and historical content of the great enigmas he unfolds from an attitude of Candide or Joha who masters the art of feigning, giving the impression of saying nothing serious. Yet, subtly, he confronts us with questions that continue to be posed to us, in these troubled times of returning to identity confinements, calls for purism, and the remnants of supposedly civilizational supremacism.

First, in seeking to know whether the original language in Paradise, as approached with a strong dose of speculation by commentators of sacred texts (the Bible and the Quran), was one or plural, Kilito opens before us a multitude of questions. The most ironic is undoubtedly the one that consists of relating, echoing Roland Barthes, knowledge and flavor, and thus the language of Adam as an organ tasting the forbidden fruit, and the language as the speech by which God taught him the names, which he can no longer recall after the fall and the ensuing forgetfulness. The beauty of the critical gesture in this text is that, in the face of nostalgic and manipulative tendencies that cling to refabricate a supposedly pure origin, the author plays with the ambiguous possibilities available to him to praise the hybrid and the indefinite.

In this sense, he invites us not to take at face value the too easily established relationship between the doctrinal uniqueness of monotheisms and linguistic uniqueness and thus the supposed superiority of a language that would be original, foundational. By playing on the fact that Syriac preceded Arabic, Kilito, following an established tradition, creates confusion between what history teaches us and what theology suggests. Thus, through this subterfuge, and without even claiming to make a metaphysics of language, he echoes in the Arab sphere the criticisms formulated by philosopher Hannah Arendt to her friend Martin Heidegger regarding the supposed superiority of German as the language of Logos, and thus of reason.

The Language of the "Barbarians"

Whether Arabs have felt superior because their language is that of revelation and the Quran, and thus sacred, or whether Roman lords considered themselves superior in their time because Latin would be the language of the dominant, history stutters and always returns to stigmatize others as "barbarians." Philosopher Barbara Cassin has already reminded us of the etymological link between the word "barbarian" and the fact that tribes make blablabla with their languages and are therefore judged to be of inferior reason. Kilito reminds us, for his part, of the semantic shift between balbala (confusion in Arabic) and the myth of Babel where, condemned to speak multiple languages without understanding each other, humans sank into chaos.

Here too, Kilito's subtlety is to leave us perplexed, faced with two possibilities: would the plurality of the languages of Babel be a divine punishment or an ideal that preexisted Paradise and that humans would strive to rediscover? The whole question is indeed whether Adam spoke one language or all languages. Because if plurality were intrinsic to the Adamites, it would cease to be synonymous with misunderstanding, dispersion, and mutual rejection and would then be a utopia to reconsider.

The subterfuge that Kilito finds to praise plurality consists of multiplying Adam's identities, first by returning to his supposed dual status as prophet and poet, author of verses offered in elegy for his son Abel killed by his brother Cain. Then, he evokes his forgetful nature which makes him even more human. Finally, he dwells on the character of another prophet, Ishmael, the first who supposedly abandoned his father's Aramaic language, Abraham, to speak Arabic. As if, through the detour of mythology and history, the author sought to reexamine the initial postulates.

Did Adam really speak Arabic? The ancient prose writers and exegetes of the Mashrek who dared to question this show us that it is enough to ask the question not to be trapped in a certainty that is inevitably ideological, a kind of belief that one would take for a (post)truth.

[1] King Faisal Prize for Arabic Language and Literature in 2023

[2] Grand Prize of Francophonie from the Académie française in 2024

[3] Reissued by Africamoude, Collection BAOBAB, African Classics, 2024

[4] Published by Actes Sud, Collection Sindbad, 2013

*Driss Ksikes is a writer, playwright, researcher in media and culture, and associate dean for research and academic innovation at HEM (private university in Morocco). He was made an officer of arts and letters by the French Ministry of Culture in 2024.

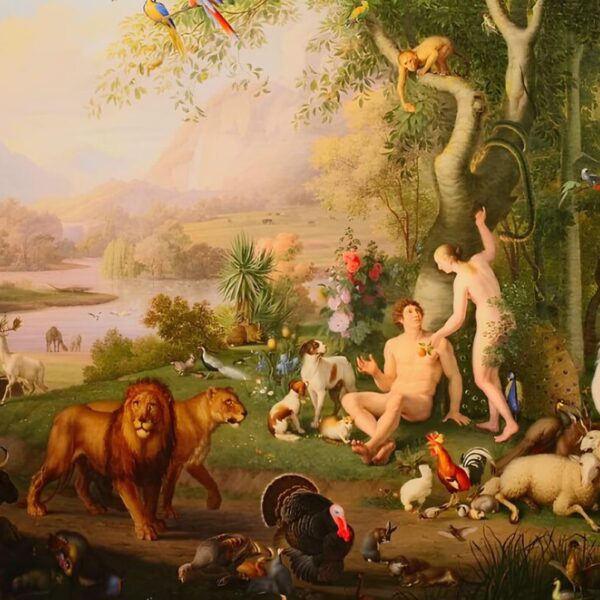

Cover Illustration: Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, oil painting on canvas by Johann Wenzel Peter (Vatican Museum)