Chickpea flour and water: two humble ingredients that together, with a little or a lot of oil, form a multitude of cakes that are enjoyed in the north and south of the Mediterranean. After the calentica, here are the panisses, a Provençal and Azuréenne specialty whose characteristics tell the story of centuries of exchanges around the Great Blue.

In 1998, in their Treatise on Chickpeas[1], Robert Bistolfi and Farouk Mardam-Bey lamented the absence of the corn pea in French cookbooks, with one exception: the recipe collections from the South. The chickpea, of Near Eastern origin, has traversed the ages and the Mediterranean shores. In Provence, while the chickpea salad of Palm Sunday has been neglected over time due to secularization, a specialty of old popular tradition bravely resists oblivion: it is the panisse, or rather the panisses since they are always eaten in multiples.

These little golden suns of chickpea flour are mainly associated today with the district of L'Estaque, an old fishing and industrial village in the northwest of Marseille, towards the Côte Bleue. One buys the fried panisses "minute" from specialized kiosks before eating them, hot, with fingers. A delight while looking at the sea, the boats, and the kids playing on the concrete breakwaters.

Panisses, it's chic

Almost thirty years after the publication of the Treatise on Chickpeas, the dry vegetable is so fashionable that restaurants dedicated to it are blooming in Marseille and elsewhere. The panisses themselves are on the menu of many establishments, in the form of discs or fries, including in Paris (yes) and even at the Élysée Palace where, in 2016, "crispy panisses" were served with lamb flavored with savory during a presidential lunch signed by chef Guillaume Gomez. The reversal is not lacking in salt. The chickpea, inexpensive to cultivate and suited to poor soils, is traditionally considered a coarse food. In Pagnol, Honoré Panisse, a character from the Marseillaise Trilogy, is indeed wealthy. But the panisse to eat is so strongly associated with the idea of destitution that "the poverty in intelligence bears its name: a panisse is also a fool"[1]. When Jean-Baptiste Reboul, a cook born in 1862, agrees to provide a recipe in The Provençal Cook[2], he specifies: "Here is a very vulgar dish from the countryside, which has a great deal in common with Piedmontese polenta and which we provide for documentary purposes."

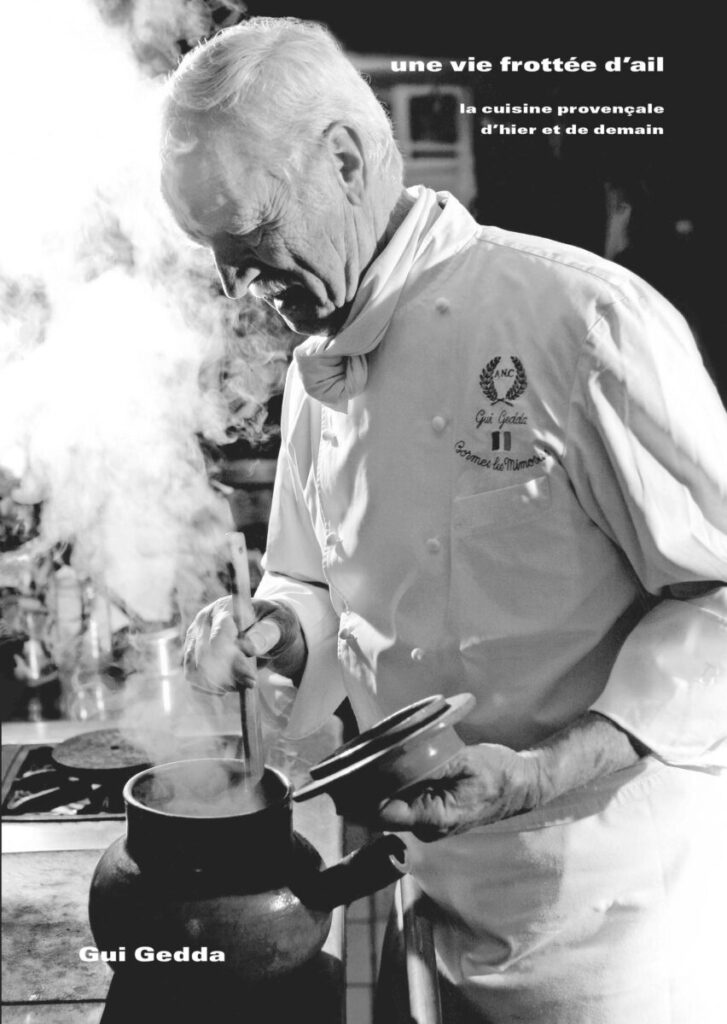

Similar observations can be found in other classic works, with the added touch of indulgence. Gui Gedda, born in 1932 in Marseille and a living legend of Provençal cuisine, writes for example in A Life Rubbed with Garlic[3]: "I do not claim that this recipe is one of our great dishes, quite the contrary. It’s 'poor people’s food.' And yet, yet, fried panisses accompanied by a good garlicky frisée salad, or even topped with a leftover warmed daube sauce, oh Good Mother! it’s still something."

Marseille, an Italian city

This persistent image of modesty is sometimes linked to the great economic migrations of Italians to Marseille. At the end of the 19th century, Frédéric Mistral defined the word panisso: "a kind of chickpea and corn flour that poor Genoese feast on"[4]. Before him, in 1839, Joseph-Toussaint Avril described the panisso as "a kind of cake made with corn and chickpea flour by Genoese residing in Marseille, who sell them there to poor people."[5] Did he confuse, as later suggested by Marcel-Blaise Régis de la Colombière without naming anyone, the "tourta tota cada" with oil, baked in the oven, and the "real panisso", cooked in water before being cooled in bowls where "it acquires consistency"[6]?

The two families of cakes mentioned with the calentica re-emerge: on one side those that, like the Ligurian farinata, are made from a mixture of chickpea flour and water baked in a hot oven; on the other, the same ingredients first prepared as porridge, one of the oldest forms of consuming cereals and legumes in humanity. Reboul, who links the second preparation to the Piedmontese and their polenta, adds an essential element to the panisse: frying, which gives flavor and texture.

This cooking technique, rooted in the culinary habits of the Mediterranean region, is particularly suited for recycling a set porridge and for street food. The félibre writer René Jouveau added, regarding panisses, that "in Marseille they were sold in the streets or in fry shops"[7]. The familiarity with panelle from Sicily, whose preparation is similar to that of panisses, may also suggest an Arab influence.

Panisses in the derby

In Palermo, just like in L'Estaque, the oil bath serves a dual purpose. The panelle are often served with fried potato croquettes called cazzilli, "little zizis" in Sicilian dialect. The stalls in L'Estaque rather associate panisses with chichis frégis, long sweet fritters reminiscent of Spanish churros (but larger, without intending to offend the Sicilians). In fact, panisses were once eaten either salty or sweet, in Marseille as well as in the Nice region.

For panisses are also present in Nice, which thus combines them with socca, a close cousin of the neighboring farinata. What a pastis! On the channel BMF Côte d’Azur, a journalist wondered in 2022 whether panisses were better in Nice or Marseille. A Nice cook replied: "The Nice panisse is better than the one from Marseille, because we put a little more love into it than they do, I think." The Marseillais don’t care as long as they have panisses.

Recipe

Gui Gedda's Fried Panisses

Recipe extracted from the book A Life Rubbed with Garlic (Les Éditions de l’Épure, 2024).

500 g of chickpea flour, 2 l of water, 2 tablespoons of olive oil, 20 g of salt, 20 cl of grape seed oil, 50 g of butter.

The day before, oil a tray 22 cm wide, 29 cm long, and 30 minutes high. Sift the chickpea flour and dilute it with 1 l of cold water. Boil the other liter of water with the salt and olive oil. When boiling, pour over the flour-water mixture. Stir with a spatula, without stopping, for 12 to 15 minutes. Pour the porridge into the tray, leveling it with a steel spatula. One must be quick. As soon as it cools, cut the dough into 3 pieces 9.5 cm wide. Wrap each piece in absorbent paper, essential for absorbing moisture.

On the same day, cut each strip into 15 equal parts, then cut each part in half in its thickness: this gives 90 fries. Fry them in a pan with grape seed oil and butter. As soon as they color, place them on absorbent paper. Salt them and enjoy hot.

At the crossroads of history and the intimate, symbols and techniques, the exceptional and the everyday, cuisine tells the Mediterranean. So let’s eat!

[1] Robert Bistolfi and Farouk Mardam-Bey, Treatise on Chickpeas, Actes Sud, 1998.

[2] Philippe Blanchet and Claude Favrat, Dictionary of Provençal Cuisine, Bonneton, 1999.

[3] My edition of the book by Jean-Baptiste Reboul, first published in 1897, dates from 2003 (ed. Tacussel). In the third edition, in 1900, panisses are not yet present.

[4] Gui Gedda, A Life Rubbed with Garlic. Provençal Cuisine of Yesterday and Tomorrow, Les Éditions de l’Épure, 2024.

[5] Lou Tresor dóu Felibrige or Provençal-French Dictionary, 1879-1886.

[6] Provençal-French Dictionary, 1839.

[7] Marcel Blaise Régis de la Colombière, The Popular Cries of Marseille, M. Lebon, 1868.

[8] René Jouveau, The Traditional Popular Provençal Cuisine, edition of Imprimerie Roubaud, 1990.

Cover Photo: Fried panisses and mayonnaise ©Mayalen Zubillaga