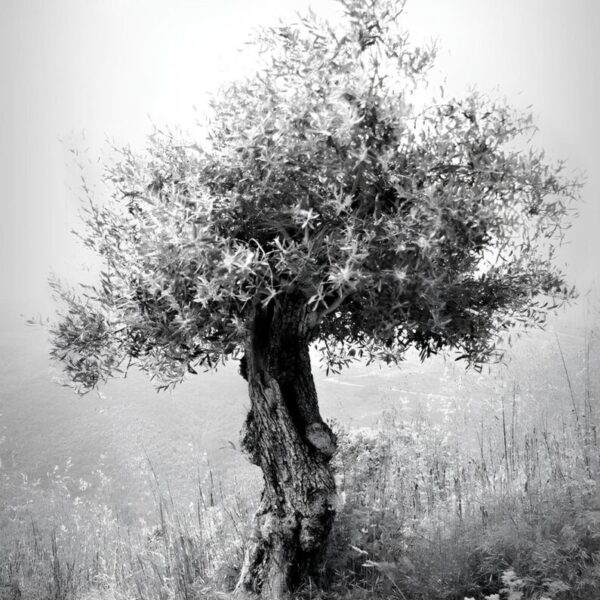

In this chronicle, broadcast last year by France Culture, Dominique Eddé invites us to take a step aside, in this region of the world, the Middle East, today so troubled and bloodied, to let us hear the whisper and wisdom of the olive trees…

Inspired novelist, let us think notably of her visionary book, “ Kamal Jann ” about contemporary Syria, caught in a sort of ancient tragedy whose inevitable mechanisms she recounts, or her recent “ Palais Mawal ”, Dominique Eddé is a singular voice. An editorialist with a sharp pen, for the newspaper “ Le Monde ” or for “ L’Orient le Jour ”, an essayist with luminous thought, to better make us know and understand “ The Crime of Jean Genet ” or “ Edward Said, the Novel of His Thought ”, she illuminates our time and narrates our world…

I invite you to hear a waking dream. Imagine for a moment….

Two minutes of waking dream. Imagine for a moment the region emptied of its populations without harm coming to them, just the time to reconnect, in their absence, with the landscape. Then imagine the restarting of all these countries, including Lebanon, modeled after their trees, just their trees.

The trunks of the olive trees weave time in their knotted bark, sometimes brown, sometimes gray depending on the time of day. Some are 1000 years old, others have just been born. Each is a kingdom unto itself. None dictates the law. Their branches rise in V shapes, sometimes one, sometimes five, sometimes more. They thin out as they grow to free the leaves which, at the slightest breeze, make the light tremble.

They are all solitary and together form indivisible bushes resembling clouds, with multicolored greens and grays. They remind me, by their sizes, shapes, and colors, of small silver fish, the bezree, that dart in schools by the tens of thousands beneath the surface of the sea.

What could be more humble and more resilient than an olive leaf with barely curled edges, so that a drop of rain can rest on it without falling? The olive trees place landscapes above countries and light above space. We, the hyperactive inhabitants of all these bloodied places with burning olive groves, would have much to gain by preferring their way of growing to ours, by imitating them, even if just for an hour a day.

The Mediterranean Library

Chronicles and Critiques

By Thierry Fabre

It is so good to immerse oneself, or to re-immerse oneself, in a tale for our time. This is the chance that Zineb Mekouar offers us in her very beautiful book “ Remember the Bees ”.

A world opens before our eyes, inscribed in a land, or better yet in a terroir like that of the High Atlas, in Morocco, in the village of Inzerki. It is here that the main characters of this story, the bees, find their place. With an old man, Jeddi, a child, Anir, a lost or possessed mother, the mejnouna, who has gone mad with sadness, and an absent father, Omar, who no longer knows how to act, disarmed, lost in the face of the world as it goes.

The Taddart obeys very strict rules, where the hives of the village are placed and assembled. It is the main theater of this story that invites us to share the mystery of the bees. Of their organization, their flight, as well as their immense fragility, in the face of the warming and the aridity that is coming and seems destined to make them disappear.

How to imagine a world without bees? A world without blooming, without the sweetness of honey that heals and repairs, without the flavor of this nectar that we no longer really know how to taste? The banality of what is consumed has erased our sense of rarity, this quest for wonder that is right there, in a spoonful of honey. It comes from that highly organized and complex universe of bees, the fruit of an art of foraging, of pollinating, of a sense of measure and a whole balance, today disrupted, between nature, bees, and humans.

Zineb Mekouar knows, through her subtle art of storytelling, how to make us enter this world where balances are as fragile as they are unstable. Beliefs are powerful in the village and the order of the bees, as well as the distribution of honey among families must be strictly respected, at the risk of a collapse of communal life.

It is a harsh world that reveals itself in the life of Inzerki, where every gesture is watched, where insularity predominates, and where a nearly immemorial order imposes itself. But it is also a place where the earth rumbles, where the tremors of an earthquake come to overturn the space, just like the lives of men, who have no other choice but to face, to stand firm, and to invent an uncertain future. Many leave for the city, to try their luck in Agadir, but misery and absurdity are never far away, a chimera of modern times.

What remains is the time and the sweetness of the bees, the time of the beauty of a tale that knows how to carry us, to sweep us away in its story, to enchant us, in seeking a pure form, a simplicity that echoes those distant whispers that make the beauty of a being… and of a book.

Zineb Mekouar, “ Remember the Bees ”, Gallimard, 2024, 170p, 19 euros

As the fall of the Assad house occurs before our astonished eyes, after more than half a century of a dreadful and destructive power, a power that imprisons and degrades, a new hope, tinged with concern, emerges from Syria. It is good, in such a context, to immerse oneself in the books of Justine Augier, who has managed to invent a form, between political narrative and literature, that invites us to open our eyes wide to the world as it goes.

In 2017, there was “ Of Ardor. The Story of Razan Zeitouneh, Syrian Lawyer ”, which allowed all those who did not know this country, Syria, to enter the Syrian revolution through the eyes of this passionate figure, unfortunately abducted and disappeared, along with Samira Khalil, wife of Hassin el Hadj Saleh, a major figure of the opposition to the regime of Hafez el Assad, father of the sinister Bachar.

This book, which received the Renaudot Prize for Essay in 2017, bears its name so well—“ Of Ardor ”. It knows how to make us vibrate, to the rhythm of political tremors, of all the atrocities and bombings, including toxic gas, that the civilian population had to endure from the regime. Figures then arose, and Razan Zeitouneh is one of them, who refuse to consent to the worst and who seek to weave links with a marginalized and despised part of the Syrian population, whom she sought to defend in her pleadings. This dive into Syrian society is particularly instructive today, as a contemptuous and orientalist skepticism is in the mouths of so many commentators. As if Syria would never manage to establish a new, fair political order. Justine Augier follows in the footsteps of Razan Zeitouneh to try to illuminate Syrian society through the prism of this luminous and stubborn figure, resolute and so profoundly human. It took her so much courage, not to give up, not to flee, and to try to resist the police and the army of Bachar el Assad, supported by the Russian army, Iran, and the Lebanese Hezbollah, not to mention the Islamist groups that abducted her. To get a more accurate or visual idea of what this hell on earth of Syria under Bachar was like, one must see the film, both luminous and moving, “ For Sama ” by Waad el Kateab, which recounts the intimacy of a Syrian hospital, constantly bombarded by Russian barrel bombs, terrorizing and shredding the civilian population, which cannot escape. If one wants to discover the misery and infamy of the Syrian regime, as well as the greatness, courage, and strength of a large part of society, which has managed to resist the worst, then this film—“ For Sama ” and this book—“ Of Ardor ” are among those rare gems that give a reason to live and the desire to never despair. The “ human margin ”, as Romain Gary would say, is thus fully visible and readable, and one emerges from it feeling enlarged, standing firm in the face of oppression and infamy. All the accomplices of the Assad house, and there are many in the world, as in France, from the far right to the far left, should permanently lose face. But the sense of human decency is not really the strong suit of “ those people ”.

Justine Augier, for her part, keeps her course and continues to want to illuminate the blind spots. Thus goes her enlightening investigation, still in Syria, about the complicities of the cement manufacturer Lafarge with the soldiers of Daesh. Her new book, “ Moral Person ”, restores to this legal designation of a company its full and entire meaning. It is an exemplary book, marked by precision in the investigation, rigor in the analysis, and integrity in listening to witnesses and actors. It is also an unyielding book, which dismantles the complicities and lies of one of the largest cement manufacturing companies in the world. It had set up a huge factory in Syria, a very large investment that served to justify all the compromises of this so-called “ moral person ”, even putting its Syrian staff in serious danger on site.

With remarkable storytelling, she recounts the struggle of an international NGO, particularly the women who embody this arduous and meticulous work to gather a bundle of serious or consistent clues, aimed at condemning Lafarge.

This narrative, which returns in several chapters, alternates with the vision of the company and its powerful CEO, Bruno Lafont, the dubious dealings of unscrupulous intermediaries such as Firas Tlass, secret agents, and others in charge of security, the battalion of lawyers mobilized by Lafarge to obtain impunity, while the company's links with Daesh are established, but not yet proven by the judicial institution. This book is the story of an unequal struggle, of law against force, told with precision and determination, where the law ultimately prevails, thanks to people who stand firm, do not back down in the face of intimidation, never give up, and do not accept the things as they are, unjust, miserable, unbearable. There is again ardor, a true continuity with the previous book, in this story of a “ moral person ” that spirals out of control and reveals itself ready to do anything, even the worst, to preserve its profits. My priority is to create value for our shareholders, calmly emphasizes the CEO of Lafarge, out of any context…

A true dive into the deleterious universe of a large company, in the heart of the tormented Syria of the Assads, Justine Augier's book should be taught in all business schools! It provides a direction, allows a company not to completely lose its compass, and to always remember that “ there is no wealth but man ”.

“ Razan Zaitouneh disappeared in December 2013, but her trajectory, like the way her being persists and continues to inspire, reveals the strength of this weapon of law, which allows, like few others, to stoke determination and the will to act. ” It is with this lesson of humanity that Justine Augier concludes her book. A “ moral person ”, undoubtedly.

Justine Augier, Of Ardor. The Story of Rayzan Zeitouneh, Syrian Lawyer. Actes-Sud, 2017, 21 ,80 euros.

Justine Augier, Moral Person, Actes-Sud, 2024, 22 euros.

Film, “ For Sama ”, by Waad el Kateab and Edward Watts, 2019, 1h44’

Photo credit: @ Thierry Fabre