The Mediterranean is a representative space of migrations in the world. This subject, publicized and politicized, is the object of simplification and commonplaces at the very moment when, for about thirty years, it is becoming more complex and diversified.

It is at the heart of this dialogue between Bernard Mossé, scientific manager of NEEDE Méditerranée, and Andrea Calabretta, a sociologist specializing in migrations around the world, particularly in the Mediterranean and Italy. This helps to better understand this specific issue.

To be continued over five weeks.

# 4 In Italy, since the 2010s, the geopolitical and economic context exacerbates the competition between incoming groups and established groups.

Bernard Mossé: If you don't mind, let's finish with a theme at the heart of your research: the construction of the collective identity of migrants, their relationship with local populations, and their own community. Perhaps through the examples you have studied of Tunisians in Italy?

Andrea Calabretta: We talked about migrants who are victims of the categories used to name them, as well as institutions that politicize and criminalize their presence. But these questions interest the entire civil society, associations, and public opinion: it is a key to understanding very typical dynamics in the construction of groups, still relying on sociologists Sayad and Elias.

To begin with, one must grasp an illusion: the perception of the migrant as a "temporary" individual. Firstly, because the migrant themselves does not want to betray their origins; then because the host society considers them as a workforce that meets a temporary need which does not require integration into political citizenship. And even the home country does not want to consider them as lost to its national population.

This illusion has consequences on the representation of the migrant, as a temporary, marginal person who does not belong to the community, and on self-representation: it is a process of symbolic exclusion that leads to social exclusions.

There is a known phenomenon in social sciences that Norbert Elias analyzed: when a new social group begins a stabilization process, dominant groups seek to restore differences, to reestablish a distance. There is this conflict, we can say, between groups that assert themselves as part of European societies, aspiring to a normal life, and dominant groups seeking to maintain their power and deny entry to those considered foreigners. The latter construct a cultural, ethnic, religious difference to distance migrants and their descendants in public discourse. I observed this process of differentiation with a group of Tunisians in Italy, in Modena, near Bologna.

This Tunisian community has been established since the 1980s. These Tunisian workers have integrated into the industrial fabric, rented and then bought houses, brought their wives and children, made Italian friends, friends from other communities, etc. They have integrated into civic life, even though in a somewhat marginal position as workers and foreigners.

In 2011, there are two new elements. The first one is the economic crisis of those years that will greatly affect the industry world with a large wave of unemployment. Immigrants, even if they have been in Modena for decades, are still considered foreigners and therefore the first ones to lose their jobs... The idea of interdependence, that they are in a certain way useful for the local society, is lost.

The second event is the Arab Spring. Many young Tunisians flee Tunisia and arrive in Italy without always having a very specific migration plan: hundreds of them pass through Modena. There is then a lot of media coverage, politicization of this presence. These young Tunisians are considered criminals. It is very clear how ethnic difference, being Tunisian, which was not a problem in 2008, becomes one in 2012. This is a very important difference that has concrete consequences on the possibility of finding housing, finding work. And this is not only the case for newcomers, but also for people who have been there for 30 years.

This is what I wanted to conclude: we tend to think that these national or cultural distinctions are natural and obvious, but that's not the case. These are constructed distinctions, over time, based on conflicts, depending on contexts and power differences. I believe that the relationships between groups in Mediterranean societies and European societies could be less tense, less violent, through a global reconfiguration of social alliances. During COVID, for example, there wasn't this big rhetoric around migration. The enemy of our society was elsewhere. The social reconfiguration generated by migrations will be a slow process of modifying social hierarchies, also involving the descendants claiming their place in the societies where they live... It will be long and conflictual, due to the resistance of established groups, but it is inevitable.

Bernard: I would like to address a question that you have not mentioned, stemming from your work, independent of the geopolitical and economic context: the fact that, within the same group of immigrants - sociologist Sylvie Mazzella has also observed this for Tunisians in Marseille - there is a distancing. Based on what she called the "neighbor-thug," the younger Tunisian, who has just arrived, and from whom one must differentiate. A bit on the theme of the common place: the last one to arrive, closes the door.

Andrea: Yes, it's a very common phenomenon. I noticed this in Modena as well, it was very evident. From my point of view, it's a dynamic that is linked to this question of social hierarchies. For Tunisians who had integrated into the local society, being assimilated with the newcomers was seen as negative. They would tell me, "We have nothing in common; when I see them on the street, I change my path...". It's about differentiating oneself from the stereotyped image that affects migrants. But the very interesting thing is the impossibility of moving away from these culturalist, ethnicized visions, from escaping this assimilation with the newcomers. I remember interviews with young women who were born and raised in Modena, with the Modena accent. It was really sad because, in the city, in bars, etc., interactions went well until the person they were talking to discovered they were of Tunisian origin...

Yes, relationships within foreign communities are sometimes difficult and conflictual, but this internal stratification is due to the attempt of migrants - settled or newcomers - to find a space within the local society. This society, however, sometimes uses these internal differences to keep them on the margins.

Biographies

Andrea CALABRETTA is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Padua (Italy), where he teaches courses on qualitative research methods in sociology. He obtained his Ph.D. in 2023 with a thesis on the transnational relations between the Tunisian community in Italy and the home country, based on the mobilization of Pierre Bourdieu's theories. In addition to relations with the home context, he has worked on the processes of social inclusion and exclusion that affect migrants and their descendants, their work trajectories in Italian society, and the processes of migrant identity construction.

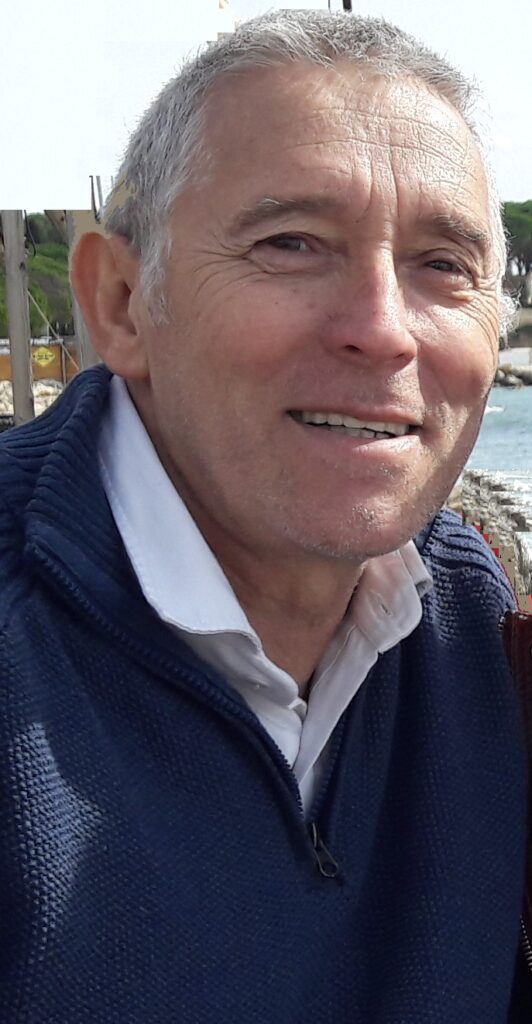

Bernard Mossé Historian, Research, Education, and Training Manager of the NEEDE Mediterranean association. Member of the Scientific Council of the Camp des Milles Foundation - Memory and Education, for which he was the scientific manager and coordinator of the UNESCO Chair "Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences, and Convergence of Memories" (Aix-Marseille University / Camp des Milles).

Bibliography Appadurai Arjun (2001), After Colonialism: Cultural Consequences of Globalization, Paris: Payot.

Bourdieu Pierre, Wacquant Loïc (1992), Responses. For a Reflexive Anthropology. Paris: Seuil.

Calabretta Andrea (2023), Accept and combat stigmatization. The challenging construction of the social identity of the Tunisian community in Modena (Italy), Territoires contemporains, 19. http://tristan.u-bourgogne.fr/CGC/publications/Espaces-Territoires/Andrea_Calabretta.html

Calabretta Andrea (2024), Double absences, double presences. Social capital as a key to understanding transnationality, In A. Calabretta (ed.), Mobilities and Trans-Mediterranean Migrations. An Italian-French dialogue on movements within and beyond the Mediterranean (pp. 137-150). Padova: Padova University Press. https://www.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/download-count/attachments/2024-03/9788869383960.pdf

Castles Stephen, De Haas Hein, and Miller Mark J. (2005 [latest edition 2020]), The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, New York: Guilford Press.

de Haas Hein (2024), “The idea of large waves of climate migrations is highly improbable”, article in 'L’Express'.

https://www.lexpress.fr/idees-et-debats/hein-de-haas-lidee-de-grandes-vagues-de-migrations-climatiques-est-tres-improbable-K3BQA6QEKRB2JCN4W47VTNCA2Y

Elias Norbert (1987), The Retreat of Sociologists into the Present, Theory, Culture & Society, 4(2-3), 223-247. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/026327687004002003

Elias Norbert, Scotson John L. (1965 [reissue 1994]), The established and the outsiders. A Sociological Enquiry into Community Problems. London: Sage.

Fukuyama Francis (1989), “The End of History?” The National Interest, 16, 3–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184

Mezzadra Sandro, Neilson Brett (2013), Border as Method, Durham: Duke University Press. https://academic.oup.com/migration/article-abstract/4/2/273/2413380?login=false

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), The Double Absence: From the Illusions of the Emigrant to the Sufferings of the Immigrant. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Sayad Abdelmalek (1999), Immigration and "State Thinking." Acts of Research in Social Sciences, 129, 5-14.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1999_num_129_1_3299 Simmel Georg (1908 [reprint 2019]), The Stranger, Paris

Based on this conversation, the AI has generated a flow of illustrations. Stefan Muntaner fed it with editorial data and guided the aesthetic dimension. Each illustration thus becomes a unique work of art through an NFT.