The Mediterranean basin is a highly populated area, and it is also one of the top global destinations for tourism. However, it is also an area where the risks of natural disasters are omnipresent: earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, and heatwaves...

This issue is the subject of a dialogue between Bernard Mossé, scientific manager of NEEDE Mediterranee, and Ante Ivcevic, specialist in natural risk management.

# 1 – There are no risks without exposure to risks

Bernard Mossé: Can you introduce yourself and present your research work?

Ante Ivcevic: I am a post-doctoral researcher in geography at Aix-Marseille University. I am affiliated with the PAP/RAC Center in Split, Croatia, which is involved in numerous actions in the Mediterranean region, mainly focusing on coastal zone management, as part of the United Nations Environment Programme. Currently, I am working on the Proteus project within the MESOPHOLIS laboratory. This project deals with risk management in the Mediterranean, particularly in coastal areas. I am specifically studying maritime planning and the management of marine protected areas. This project is carried out under the supervision of Sylvie Mazzella, a researcher in sociology.

Bernard: Can you provide us with a typology of disaster risks in the Mediterranean?

Ante: First of all, it must be clarified that we cannot talk about risks without talking about exposure to risks and therefore the vulnerability of populations.

The natural component is the basis of the analysis. And the Mediterranean Sea brings together many components: for example, the telluric component is very important there with seismic risks and volcanic eruptions. There is also the climatic component, including the risk of floods. Due to climate change, we are witnessing an increase in the frequency and volume of precipitation, extremes. It should not be forgotten that we are in a subtropical zone with a whole change that reduces or shifts our four seasons.

But I want to come back right away to the fact that when a tragic event occurs, a disaster, its dimension depends on us: when there is a large number of deaths, for example with the heavy rains we have experienced in Bulgaria, Greece, and Libya, it is greatly exacerbated by human action: poor construction or mismanagement of water dams… So, yes, we are in an area of many risks, but mainly because of what we have done, or because of what we have not done.

Bernard: It is a constant in your research to study risk management as an interface between natural parameters and societal responses.

Ante: Yes. When I was in my thesis, I participated in a World Congress on Resilience in 2018, in Marseille. A researcher from a university in London spoke to point out the geological or geomorphological risks, but mainly to declare that the main cause of risks was corruption: he referred to his work in southern Italy. I emphasize this point: if we do not pay attention to doing things correctly, we will have seriously aggravated consequences in an area that is seismic: I am talking about our constructions, our buildings, our cities, our bridges, our dams… This is particularly the case in Croatia: we have had major earthquakes, in 2020 in the capital Zagreb, and its surroundings. Fortunately, we did not have many deaths and injuries, but the poor constructions are entirely responsible. They need to be renewed. It is the same in Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa where construction is probably not up to date. It is different in Japan, for example, where awareness and technology allow for better protection.

Also, I cannot delve too much into this sociological dimension because it is not my field, but some images are truly striking: when we see the level of disasters in Turkey or Libya, and we say that we could not do anything… Of course, we could do something, we can do many things: it is a political decision about risk management! Yes, humans are responsible, we are responsible for this management. It is not nature that manages human constructions…

# 2 – There are multi-risk regions…

Bernard: Cognitive sciences have extensively studied this gap between consciousness and behavior, thought and action, intention and action. We will talk about this again. But I would like to go back to one point. Can we say that the typology of risks is greatly dependent on the regions in the Mediterranean? For example, you have worked on the northern part of Morocco, which you describe as a multi-risk region. Are there areas that are much more dangerous than others?

Ante: One day, a Moroccan administrator from the region of Tangier-Tetouan called out to me: “You say that in our region it’s a multi-risk area… but in your region, there are many places with multi-risks too…”. Indeed, to qualify a region as multi-risk, it only takes two or three types of risks, and yes, this applies to almost the entire Mediterranean.

Now, it depends on which level. Because we are really between two tectonic plates, Eurasia and Africa. There are regions, and therefore populations, that are much more exposed: let’s compare, for example, Sardinia and Sicily, on which I had the opportunity to work: I think that Sicily has much more risks than Sardinia. First, it is much more populated and denser, with over 5 million inhabitants on less than 26,000 km2, while Sardinia has less than 2 million inhabitants for a slightly smaller area. Furthermore, Sardinia is part of this older piece of land: earthquakes are much weaker there. Sicily being further south, the impact of heat is also more pronounced.

Bernard: The difference in latitude is still quite small…

Ante: Yes, but density also plays a role in heatwaves. The fact that an area is denser in population and construction worsens the level of risks.

If we talk about Croatia, we have the mountain range, the Dinarides, and all this coastal part is very exposed to seismic risks. In terms of fires, we do not have the experience that other countries at comparable latitudes have, like France, Italy, Spain, or slightly further south like Portugal and Greece. I haven’t made any statistics, but I believe that for these two countries, the risk is still more pronounced. Fires in Greece indeed start earlier than here in Croatia.

Yes, I am happy that we are further north, but we can see that even Central Europe and Northern Europe are experiencing change. Regarding heatwaves, heatwaves, and strong storms, no one can say in this changing world: I am safe.

# 3 – Natural disasters are not a novelty, but they are dangerously escalating

Bernard: Let’s take a step back in history. Can’t we say that natural disasters have always existed? By mentioning major historical disasters, such as those of Pompeii, or going even further back with the eruption of Santorini, which would be linked to the myth of Atlantis? Can’t we say, in a way, that it’s a constant?

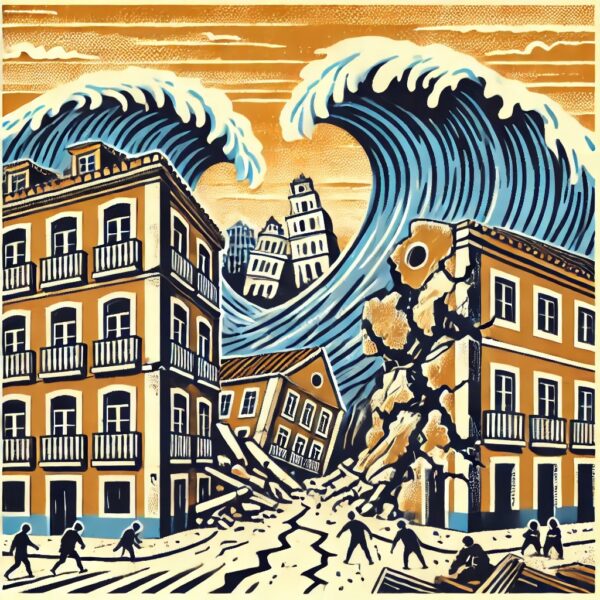

Ante: I think so, they have always existed. We have in historical memory the cases you mentioned. But, for example, in 1755, when Lisbon was completely destroyed by an earthquake, a tsunami, and the monstrous fire that followed, do you know what amplified the disaster: it was the candles in the houses, the churches, it was November 1st, All Saints’ Day…! First, there is a natural event, as in this case, the earthquake, and then there is the lack of foresight and ignorance of people. What is a tsunami? Some saw the enormous mass of water receding, they went to the seashore to see it and were swept away…

A disaster is always a combination of nature and humans. But while natural events are always present, they are now much more serious than before. This is the case with storms, obviously, and particularly so in coastal areas, at the border between land and sea, due to overpopulation and over-construction, but also on the banks of rivers which are overly developed…

So, yes, I agree with you, we already had all this before, but we have greatly worsened the situation with our behavior and activities.

Risk awareness is not natural: it must be worked on

Bernard: I obviously do not want to absolve politicians of their responsibilities, but the awareness of the worsening of natural disasters due to climate change is relatively recent. Many of these buildings were constructed in the 1960s-1970s, when this knowledge was not as acute. So, there is the question of awareness that you emphasize a lot in your work, and there is also the ability of scientists to convey their findings to the population.

Ante: The question of consciousness is important, but it is not central. For example, during my research project at the VUB University in Brussels, my field of study was Catania, in Sicily; I conducted interviews with three groups of people: scientists, administrators, and civil society. I noticed that everyone was aware that the city is located in a seismic and volcanic area, and of course, it is related. They know the history of Catania, that it has suffered a lot from earthquakes, especially in 1693, and that the neighboring city of Messina was destroyed in 1908. But, as you mentioned, due to the buildings that were constructed during the economic boom of the 1960s and 1970s, when you look at these buildings today, and you know that an earthquake can happen every day, it obviously scares me…

While talking with my interlocutors, even with scientists, they emphasized the economic issue. Anticipating, renovating, rebuilding is too costly. More seriously, a researcher, urban planner, who had participated in a civilian construction project of her own house, explained that she had invested a lot in a “tip-top” project, except for seismic risk, because it costs too much money.

But let’s also look at it from a broader perspective: there is an economic issue in Europe, but it may be much more difficult to invest in the Middle East or North Africa.

Yes, I totally agree regarding the issue of consciousness. However, sometimes people are aware, but think that it won’t really impact their lives. You can be informed about a subject without deeply feeling it.

When I felt the earthquake in 2020, having studied seismology and geophysics did not help me. My reaction was so irrational seeing the road with the passing wave, the seismic wave. It’s an irreplaceable experience. One thing is to know, to have that knowledge, even technical or scientific, another thing is to incorporate that knowledge and react or even anticipate. For example, in Croatia, I believe we are very aware of heatwaves because we have the experience, much more than in Northern Europe obviously.

# 4 – Information is not enough: it is necessary to involve the populations in the decision-making process

Bernard: I come back to the essential question that is at the heart of your work, the information of populations and prevention. You have already touched on it: people are becoming more aware of the risks, disasters, and the necessary adaptation to climate change and transition more generally. But it is clear that this awareness, through increasingly widespread information dissemination, is not enough to overcome the barriers to behavior change. In your opinion, what needs to be done beyond information campaigns so that populations can change their behavior?

Ante: Thank you very much for this question. It is very interesting and important, and not at all simple. I believe that many leaders of each country are looking for ways to communicate and convince people to act and accept to adapt in the interest of the whole society. But it’s difficult. Trust is the key: the trust of the populations in scientists and leaders, but also the trust of the latter in the population. When leaders and scientists address the population, it must be a mutual relationship, a real “exchange”, in the sense that it is less about providing solutions and giving orders than about understanding together where the obstacles to adaptation are and proposing steps forward.

The obstacles are not always economic: I have just spent seven months in the United States, in Boston, Massachusetts, a very wealthy state. There, as everywhere in the United States, as you know, there is a great problem of trust towards scientists. And the debate around climate change is politically very polarized and therefore blocked.

I am afraid that this negative societal movement may influence public debates here in Europe.

We can also attribute the COVID crisis period because communication was not good at all: politicians, in general, highlighted the best possible information from scientists to justify the measures taken. But there were populations that were not able to follow them; especially the most vulnerable people.

For example, in the north of Morocco, where I am currently working on coastal planning, many people whose work was related to tourism lost their jobs during COVID because the borders were closed, as in many countries. It is the women, who are already economically more vulnerable, who have been most affected…

So, I don’t know if all of this was planned by the leaders but could have definitely been avoided if the local populations had been consulted in some way.

Now, I am going back to natural risk management and its connection with the inhabitants: I think it is truly essential. On one hand, we cannot have the resources and time to work with everyone, with millions of people; but we can work with citizen associations, and thus rely on a greater awareness of the population. It is important because scientists convey the results of their research, but decision-makers must include other issues. Sometimes, scientists do not understand why adaptation to climate change is not faster. But there are social and economic issues that are very important for populations, especially vulnerable populations; because, obviously, it is not the same for the rich and the poor to adapt. Today, we are working more on this notion of “climate justice,” of “environmental justice.”

#5 – Awareness of dangers depends on trust in scientific and political discourse

Bernard: I am coming back to the brakes on behavior change. Many of them have been identified, especially by cognitive sciences, and researchers have highlighted what they called “the inaction triangle” – the idea that an individual changes only if others change as well. For example, companies say they will adapt only if policies themselves initiate the movement and if consumers change their consumption habits; citizens only move if policies encourage them to do so, and policies say they depend on companies, etc… There is a sort of vicious circle that induces inertia. Have you worked on solutions to this obstacle?

Ante: Personally, no, I would be really happy if in the election debates, politicians really took into consideration these issues so that the populations could then take them on. Among the questions we asked our future prime ministers or presidents, we have two questions that deal with adapting to climate change and energy transition. This is really important. It encompasses the whole discourse and I would really like the debates to remain outside the right/left opposition, because it is about confronting a very present reality that goes beyond these divides. We must seek, with the different political options, the best solution and stop debating whether it exists or not. Because that’s where…

What is the best solution? I don’t know, it depends on the companies, the contexts, their capabilities, but we need to work together on concrete solutions and not on deep, philosophical causes. We must be much more focused on the solutions and probably at the level of small communities that can contribute a lot and help combat inertia locally by bringing local decision-makers, citizens, and businesses together at the same table, all committed to finding solutions for transition and adaptation. It is at these local or regional levels that we are trying to contribute as researchers.

Bernard: It seems to me that you also address in your work the issue of the responsibility of scientists themselves. We can see, for example, that the information disseminated by the IPCC does not have the desired impact. Perhaps what is at stake are the scientific mediation skills that we promote in our association and with the UNESCO Chair that we hold with Aix-Marseille University. Undoubtedly, proposing solutions, as you say, is necessary but not sufficient. There may be a question of collective writing, of shared storytelling of realities and solutions.

Ante: Scientific responsibility is especially important in societies like ours where science is largely a public good. Researchers are generally civil servants paid by taxes, so by the population, and we must have this sense of duty to give something back to society. I totally agree: we have this responsibility. But on the other hand, there are different profiles of scientists: some are into pure research, others are more skilled in training or even raising awareness and educating young people, others in collective research… We must first understand that there are different ways to contribute. Personally, I think I am very skilled in managing discussions, roundtable talks. When I started working, after my thesis, for the Priority Actions Programme (PAP/RAC) in Split, I didn’t know what it meant to “manage a roundtable discussion.” I thought: there is a person asking a question and people responding. It’s much more than that and it aligns with what you were saying about scientific mediation and “shared narrative.” Gradually, I discover that it suits me, that I would like to engage a little more in that dimension.

I totally agree, there are different ways for researchers to contribute and it would be really sad if we just stuck to our approach: analysis, production… Because scientific production is very important and very useful, it’s the basis, but it’s not enough. It’s like, for example, a good piece of meat that is prepared perfectly, but no one does anything with it and it just goes to waste…

Bernard: Perhaps there is also a lack of understanding in the audience of what the scientific approach is, of its relationship to truth. You mentioned the period of Covid, for example. But we could mention many other examples in which populations have lost confidence in science because they do not understand what the scientific approach is, its temporality, its continuous search for an evolving truth, which is built over time. Could you perhaps say a word about the knowledge of natural disasters and its evolution?

Ante: There is always new knowledge. I hope that we are able to understand that we are not perfect and that we need to learn from others. Often researchers present themselves as scholars, “I know everything about my field and I have nothing to learn… I am here to reveal my knowledge.” And that is really false. In relation to major societal issues, such as adaptation which is not a small matter, I mean it is not just a technical issue to solve, with a perfect barrier that would contain all risks: it is a change that really concerns the whole society. And scientists may represent only 1, 2 or 5% of this society, they do not represent 50%. So, we are just a piece of a rather complex system. As you rightly said, solutions need to be found at the academic level and then submitted to citizens to choose and decide together. A solution that is not accepted by the majority has little chance of success.

But scientists must be clear in informing the populations: not only providing the numbers but also how they were obtained, what is its probability, what are the variations and margins of error. And to say that, perhaps, in five years, the knowledge will have evolved and there will be new proposals…

So, I don’t think that scientists have all the power or all the responsibility. During COVID, no one was thinking about climate change anymore. And now we have inflation, wars… It’s a problem.

We must understand and make it clear that we are just a part of a complex system and that we must work together to find solutions.

# 6 – Public research appears to be the most reliable

Bernard: Speaking of the academic world, it seems to me that you mentioned a distinction between researchers funded by public policy who would have a greater awareness of the common good. Would you make a distinction between continental research and Anglo-Saxon, American research?

Ante: That’s my point of view, indeed. In general, I appreciate much more information produced by a national research center, for example, when talking about Europe, than information produced by experts funded by a private company. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that they haven’t produced good information. It just means that I personally have more trust in a national research center… I support this European model of funding public research. It is essential and unfortunately, we are funding it less and less. Yet, it is very important and is, I believe, our strength compared to the United States.

Bernard: Do you think this is one of the reasons for the lack of confidence?

Ante: I believe so, and I really wish that we do not follow the Americans in this field. There is a lot to learn from them in the quest for solutions, but not the privatization of research… But that’s my opinion. Perhaps there are some in favor of this perspective.

Bernard: I think we agree on this point. I would like to come back to what you said twice about the economic obstacle: it seems to me that some solutions are not adopted not because they are expensive but because they are costly in the short term… In other words, what is the obstacle is not the economic question, it is the short-term vision. In the long term, some constructions taking into account seismic risk, for example, would be highly profitable, and not only in terms of human cost.

Ante: Vision is important because it helps us organize our activities. This vision can be disrupted by a state of emergency. On the other hand, new elements can modify our vision. But the direction must be clear, because without vision, every media event will disrupt our action.

For example, today, the urgency of war has nothing to do with adapting to climate change. We cannot forget that we must continue our adaptation work. I believe that public research centers have this vision and approach to different time scales, short and long term. That is also why, I come back to it, it is necessary to support public research.

# 7 - Effective work in combating risks often occurs after the disaster

Bernard: I would like us to finish on a question, let's say in a sense, more positive...:

I have worked on mass crimes and the genocidal process. And often, we come across this observation that unfortunately, there needs to be disasters for consciences to awaken and mentalities to change. Do you have examples of disasters that have led to changing mentalities, advancing things, and maybe even allowing a longer-term vision? Natural disasters can paradoxically, how to say, be a source of hope?

Ante: Yes, a very good example is the earthquake and tsunami of 2004 in the Indian Ocean that struck Indonesia, Sumatra, Sri Lanka, southern India, and western Thailand. Over 250,000 people died or went missing... It was on December 26, 2004. It was at that moment, at the age of 16, that I decided to study geophysics, and I am really attached to this event because I could not understand how it was possible in societies that had experienced earthquakes before. How was it that no one knew not to go there to collect seashells...? It's a tragic example, but ultimately after this event, countries came together in a prevention network. And today there is the Early Warning System, a system of prediction and anticipation. It's a system that works very well. Now, if there is a strong earthquake in the ocean, the countries that could be affected are immediately informed. 2004 made this possible... There are surely other examples that don't come to mind, but this one, I am emotionally attached to.

Bernard: I can maybe give you an example that comes from my interview with the biologist Karl Matthias Wantzen, a river specialist: the ecological disaster of the Sandoz factory in 1986 in Switzerland, following a fire that polluted the Rhine throughout the downstream hydrographic basin, all the way to the sea. The regions involved have implemented measures to prevent a new disaster of this kind. Effective up to this day...

Ante: Yes. Progress can be seen in the development of riverbanks. It can be said that coastal planning management is also advancing: we are developing coastal plans as part of the Priority Actions Programme in Split, crossing with the practices of France and Italy. Personally, I am involved in developing a similar plan in Morocco. In countries that have ratified the Barcelona Convention (in 1976), with the protocol on integrated coastal zone management, there is an incentive to establish a setback of 100 meters from the coast to allow space for fluctuations and avoid damaging infrastructure and property. This is an example that shows it is truly possible on the shores of the Mediterranean; it is true that we have not been very attentive for about a hundred years, when the first seafront was built.

Bernard: So, to use your word, there is a question of courage...

Ante: Yes, we come back to the decision-makers, because we also rely on them. We have the information, the law is there, but it takes courage to enforce it.

References

Ante Ivcevic, specialist in risk management in coastal areas is a postdoctoral researcher in geography at Aix-Marseille University. Affiliated with the PAP/RAC Center in Split, Croatia, as part of the United Nations Environment Programme. He is currently working on the Proteus project within the MESOPHOLIS laboratory at Aix-Marseille University, focusing on risk management in the Mediterranean, under the supervision of Sylvie Mazzella, a research director in sociology.

Bernard Mossé Historian, Research, Education, and Training Manager of the NEEDE Mediterranean association. Member of the Scientific Council of the Camp des Milles Foundation – Memory and Education, for which he was the scientific manager and coordinator of the UNESCO Chair “Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences, and Convergence of Memories” (Aix-Marseille University / Camp des Milles).

To go further

1. Ivčević, A., Mazurek, H., Siame, L., Bertoldo, R., Statzu, V., Agharroud, K., Estrela Rego, I., Mukherjee, N. and Bellier, O., 2021. Lessons learned about the importance of raising risk awareness in the Mediterranean region (north Morocco and west Sardinia, Italy). Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 21(12), pp.3749-3765.

https://hal.science/hal-03478720

2. The article titled "Indicators in risk management: Are they a user-friendly interface between natural hazards and societal responses? Challenges and opportunities after UN Sendai conference in 2015" was authored by Ivčević, A., Mazurek, H., Siame, L., Moussa, A.B., and Bellier, O. in 2019. It was published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, volume 41, page 101301. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212420919300585

3. Ivčević, A., Statzu, V., Satta, A. and Bertoldo, R., 2021. The future protection from climate change-related hazards and the willingness to pay for home insurance in the coastal wetlands of West Sardinia, Italy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 52, p.101956.

4. Ivčević, A., Bertoldo, R., Mazurek, H., Siame, L., Guignard, S., Moussa, A.B. and Bellier, O., 2020. Local risk awareness and precautionary behavior in a multi-hazard region of North Morocco. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, p.101724.

5. Agharroud, K., Puddu, M., Ivčević, A., Satta, A., K

From this conversation, the AI has generated a stream of illustrations. Stefan Muntaner fed it with editorial data and guided the aesthetic dimension. Each illustration thus becomes a unique work of art through an NFT.